Editor’s note: This story has been revised to report that the Pesticide Educational Resources Collaborative has 115 commonly used label terms translated into Spanish, not 115 labels.

Pesticide labels are in English. Many applicators speak Spanish.

Noticing that obvious problem was never the problem, said the University of Washington designers of two translation phone apps targeting applicators. “We’re not the first to think of wanting it,” said Kit Galvin, a research scientist and certified industrial hygienist with the UW School of Public Health and the Pacific Northwest Agricultural Safety and Health Center.

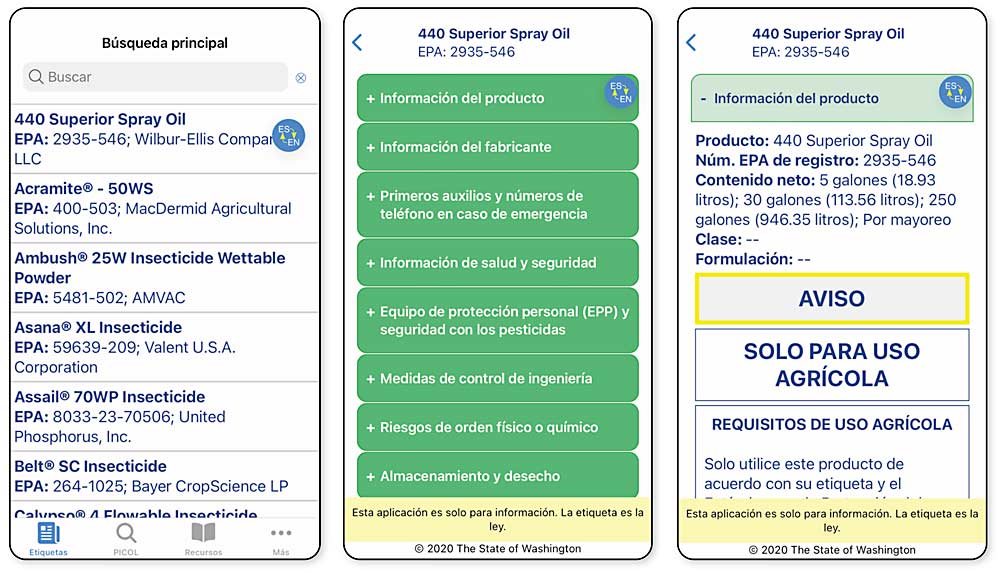

Galvin and her team released one phone app in August 2020 that translates key portions of common apple and pear pesticide labels, and they plan to unveil the commercial version of another app this fall after they recruit some grower collaborators. Both will provide translations regardless of cellular service or WiFi connection.

The current app, “¡Etiquetas de pesticidas, ahora!/Pesticide Labels, Now!” is free on app stores and includes translations of portions of labels for 40 chemicals commonly used in the apple and pear industries. “It’s not all the labels by any means,” Galvin said.

The translations include information about personal protective equipment, re-entry intervals, preharvest intervals, first aid, environmental safeguards and other key details.

With the app downloaded, the user may access those 40 translations without a connection to WiFi or cell service. Within connection range, the app features links to more resources, such as full labels from Washington State University’s Pesticide Information Center OnLine database, the state Department of Labor and Industries, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the Pesticide Educational Resources Collaborative.

Around 50 people were involved in official testing of the app, though more than 100 additional people have reviewed it since then, Galvin said.

The second app — a bigger and more complex program called “PestiSeguro/PestiSafe” — is a work in progress and will feature most labels for Washington specialty crops, with sections about pollination, drift risks and other measures not included in the first app. The developers plan to add labels and features upon request as growers sign up, Galvin said.

Galvin’s team is seeking grower collaborators for the spring and summer, who will get free access for 2021.

Development of both apps was funded by grants totaling more than $500,000 from multiple sources, including the Washington State Department of Labor and Industries, Washington State Department of Agriculture, the University of Washington and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

Galvin and the university want the commercial app, PestiSeguro, to be financially sustainable. The university plans to commercially release it for a subscription fee starting in the fall.

Galvin cautioned that while both apps are intended to provide helpful information, the original pesticide labels carry the weight of law.

Industry reaction

“I think it’s a great idea,” said Sarah Rasmussen, orchard safety manager for Gilbert Orchards of Yakima, Washington, which tested the free app. The company likely will at least equip managers and foremen with the tool, she said.

State regulations require that companies verbally instruct applicators in five sections of each label of a chemical they use for the first time each year.

“There’s a really big problem there if you don’t speak Spanish and they don’t speak English,” Rasmussen said.

Jeremiah Turner, a ranch manager for Gilbert Orchards, found the free app handy in either language.

He found himself using it to look up details — in English — such as required PPE and re-entry intervals, regardless of connectivity. Without the app, he would either walk back to his truck to check his spray book, visit the spray shed to read the physical label on the canister or Google it, which itself takes time even with a good connection. “I really liked it for how easy it was to access,” Turner said.

Turner is considering issuing his “spray boss” a smartphone just so he can have the app, too. The Spanish-speaking employee who reads English well told Turner the translations were useful. But Turner also sees a worker safety benefit in the app. If someone got a chemical in their eyes, Turner said, the first aid section is just a phone click away.

“I want him to just be able to have that access,” Turner said.

Eladio Gonzales, farm manager for G.S. Long Co. in Yakima, tested out some of the translations with a few of his workers. He likes the app, but he wants to make sure it isn’t used to replace pesticide education efforts.

“In combination with using the app, I believe it’s very important that we don’t lose focus on educating the people who are applying pesticides,” Gonzales said. “The pesticide label app does a good job to help understand how the product works and gives info on some of the risk factors involved when applying. Being able to offer training in a language people can understand is crucial for the safety of the handler and other surroundings.”

A service such as the translation apps is long overdue, said Jacqui Gordon Nuñez, director of training, education and member services for the Washington State Tree Fruit Association. Applicators may not necessarily blame an accident on their limited understanding of an English pesticide label, but language barriers are always a concern, she said. The federal Worker Protection Standard requires training pesticide applicators in a manner they can understand, such as by using a translator.

Gordon Nuñez helped Galvin’s team find growers to test the apps, and she reviewed some of the early translations herself. Making sure they were accurate was one of her primary concerns. “If they are going to translate something as important as a pesticide label, it has to be 100 percent accurate,” Gordon Nuñez said.

She believes they are.

Tricky translations

Indeed, translating was tricky, said Pablo Palmandez, one of Galvin’s colleagues at the University of Washington who led the translation efforts.

Palmandez took pains to translate into usable language but also remain accurate, avoiding jargon and “Spanglish.” There are a lot of bilingual workers, managers and growers in the industry, at least at a conversational level. But pesticide labels are rife with technical language.

For example, the Spanish word for the verb “to spray” is asperjar or rociar. Many Latino workers in the U.S., however, use espreyar — a hybrid of Spanish and English.

To walk that fine line, Palmandez searched academic journals for specific terminology, cross-referencing that with common Spanish language and speaking to industry groups and companies. “It was challenging,” he said.

Palmandez grew up on Mexico’s Pacific Coast in Nayarit and studied agronomy, specifically pest and disease control, at an agricultural college in Chapingo, Mexico. When he moved to the U.S. to work for the Mexican export inspection office in Washington, he still had some learning to do.

“I needed to learn Spanglish,” he said with a laugh.

A common lament from Latino managers, even those who speak English well, was that they had no way to read pesticide labels in Spanish. Some of the feedback from the test group revealed that even bilingual managers understood labels better with the translations.

Other agencies and organizations have made efforts to translate pesticide information as well.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has a 17-page guide listing translations for common terms, both technical and routine, such as air purifying half-face (elastomeric) respirator and the Spanish words for caution, warning and danger — precaución, aviso and peligro. Meanwhile, the Pesticide Educational Resources Collaborative, an agreement between the EPA and the University of California, Davis Extension, has translated 115 commonly used label terms into Spanish. The National Pesticide Information Center also has a Spanish section.

Those tools are useful, Palmandez said, just not extensive enough.

“It’s useful, it’s a good document,” Palmandez said. “However, there are more materials to translate that are in the labels for health and safety.” •

—by Ross Courtney

Call for collaborators

The Pacific Northwest Agricultural Safety and Health Center is looking for specialty crop growers to test out one of its pesticide label translation phone apps. Collaborators will receive free access to the app in 2021, before the center releases it commercially on a subscription basis. If interested, email Kit Galvin at kgalvin@uw.edu.

Leave A Comment