Exports of U.S. apples are lagging for a host of reasons, and the slowdown may continue for a while.

Crowded ports, a lack of truck chassis and other infrastructure issues are contributing to the problem. Lingering tariffs are another factor. Shifting variety preferences also play a role.

Add it all up, and the U.S. apple industry may face a future with fewer exports, at least in the short term, to traditional powerhouse markets such as India.

“It’s going to be a tough year,” said Mark Powers, president of the Northwest Horticultural Council, which represents Washington and Oregon fruit producers at the federal level.

Exports and the domestic market for apples go hand in hand. U.S. consumption has been relatively flat for decades, meaning the industry relies on exports to keep domestic prices high. A 2020 Washington State University economic study determined that for every 1 million export boxes redirected domestically, FOB prices drop 50 cents.

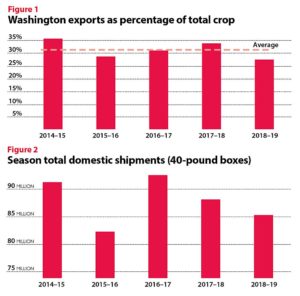

The bulk of U.S. apple exports, valued at an average of $1 billion annually before 2018, are grown in Washington, which historically exports about 30 percent of its crop. In the 2017–2018 shipping season, Washington exported 44.9 million 40-pound box equivalents of apples to global markets. The state hasn’t cracked 40 million boxes since then. At the end of November, exports for the 2021–2022 season were on pace to fall 9.6 percent below 2020–2021, which itself was lower than the previous year.

President Joe Biden has barely moved the needle on global trade disputes that started under the previous administration’s 2018 Section 232 tariffs on steel and aluminum, which led to retaliatory tariffs on agricultural exports, among other things. In late October, the U.S. dropped the steel and aluminum tariffs against the European Union. The U.S. ships little fruit to Europe due to phytosanitary restrictions, but the tariff removal may lead to efforts in other markets, said the U.S. Apple Association.

“We hope this announcement will mean a similar review of the steel and aluminum tariffs imposed on India and China,” said USApple CEO Jim Bair in a news release. Before the extra tariffs, India was the second largest export market for U.S. apples. China was No. 6.

Relations between the U.S. and China are sour overall, and agricultural trade is low on the priority list. India and the United States have recently resumed talking about agricultural trade, according to Powers.

Washington apple exports to India dropped from nearly 8 million boxes in the 2017–2018 shipping season to about 2.7 million the next year. It’s fallen even more since. In late November, trade representatives from the two nations met for the first time since 2017 under the Trade Policy Forum, a nuts-and-bolts negotiation format between the two countries. They discussed tariffs but didn’t drop any.

Even if negotiations succeed, exports may not return to their pre-tariff levels, at least not in the short term, said Todd Fryhover, president of the Washington Apple Commission, which collectively markets Washington apples in foreign countries.

“Maybe we need to have less priority on India,” Fryhover said.

Before the trade disputes, India served as a major outlet for Red Delicious apples. But Washington produces fewer Reds these days, in favor of higher-profit Honeycrisps, club varieties and Cosmic Crisp, a managed variety expected to surge in volume in coming years. By the time trade conflicts are resolved, Red volume could drop even further, while Turkey and Poland have increased their exports of Red Delicious apples to India, Fryhover said.

If tariffs come down, he said, America’s best bet in India may be marketing more expensive varieties to the 10 or 15 percent of shoppers who frequent retail stores rather than cheaper, open-air markets.

Moreover, in reaction to the uncertain markets in China and India, the Washington Apple Commission has doubled down on what Fryhover calls the “home court” — Mexico and Canada, two tariff-free countries that alone account for nearly half of Washington’s exports year to year. The apple commission doubled promotions to $2 million per year in Mexico, making use of increased Agricultural Trade Promotion dollars, federal funding allocated to help export industries adjust to tariffs.

Also, the U.S. trucks apples to Canada and Mexico, avoiding the current complications of ocean shipping — the supply chain crisis dominating headlines for the past six months — which may even get worse. West Coast port operators and the union that represents dockworkers are due for a new collective bargaining agreement on July 1. In late November, the union rejected a contract extension offer, according to the Journal of Commerce.

Ports and dockworkers have long had a contentious, sometimes violent, relationship. Since the advent of container shipping in the 1950s, unions have opposed technological developments that displace workers. Nearly every contract negotiation between the Pacific Maritime Association, which represents the administrators of 29 West Coast ports, and the International Longshore and Warehouse Union since the 1990s has resulted in cargo delays, the Journal reported, including a six-month work slowdown that disrupted the 2014–2015 season. The Northwest Horticultural Council estimated that disruption cost the apple and pear industry $95 million in lost sales opportunities.

The unprecedented surge in consumer demand causing backlogs at ports, a lack of available containers in the Northwest and a dearth of truck chassis and drivers only make the problems more complicated.

“It’s not clear that anybody can fix the problem in the short term,” Powers said.

—by Ross Courtney

there shouldn’t be any need to import fruits rather India should start expanding it’s export chain and give the Indian taste to the world.