Drones scare birds.

A Washington State University researcher wants to figure out how to use that to a grower’s advantage.

Manoj Karkee, a biological systems engineer for the university’s Center for Precision and Automated Agricultural Systems, spent three years measuring how hovering an unmanned aerial system — a drone —affected the population of birds in both a wine grape vineyard and a blueberry field.

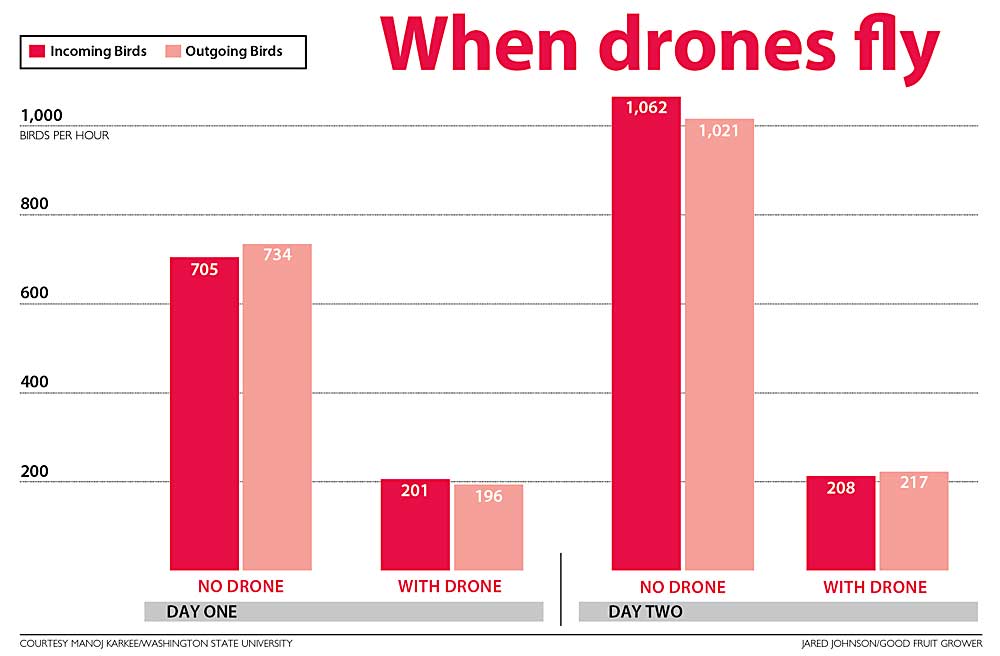

It kept them away — by a factor of five sometimes, compared to the control.

Karkee thinks the approach will work commercially, and some companies already offer drone bird-deterrent services. The drawback is that federal regulations still require drones to be piloted, preventing full automation, but Karkee thinks the technology will be ready if and when the rules allow.

“We have demonstrated capability and feasibility of controlling the damage caused by these birds, and we hypothesize that this will be a solution that will be more robust” than existing methods, he said.

The experiments were pretty simple. His research team placed cameras looking down the four field boundaries and collaborated with a biologist to count the birds arriving and leaving. Most were robins and finches, known fruit-eaters.

They did that one day without drones and then repeated the experiment with a team member flying a drone. The field researchers also counted birds, as a way to validate the camera research.

Some days, they just let birds do their thing. Other days, they flew the drone.

And what a difference.

Graphic: Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower)

Bird visits were between 3.5 times and 5.1 times higher over a peaceful vineyard compared to one patrolled by a drone. The fruit damage was higher in the untreated block compared to the drone-policed block, as well.

The blueberry field was 15 to 20 acres in size. The vineyard was 5 acres.

Funded by the Washington Blueberry Commission and internal Washington State University grants, Karkee and his team ran the experiments in 2017 and 2018.

The results gave Karkee proof-of-concept. “This is effective,” he said. “How much, we don’t know.”

There are some caveats. For one, weather is different every day, so birds simply may not have been as active the day his team flew drones. Meanwhile, just because it works in his test plot doesn’t mean it will work as well in a plot that has different surroundings.

Also, birds are adaptable. Any grower will tell you they habituate to most tools you throw at them, and growers have tried plenty over the decades — reflective strips, giant inflatables, sound cannons, lasers and sugar coating. He’s not sure if birds would get used to drones over time, but he has high hopes. Drones can fly in random patterns.

The next step is automation. Federal Aviation Administration rules currently dictate that drones may be automated, but an operator has to man the controls within line of sight to take over if something goes wrong. Karkee envisions a day when drones become more common, the rules relax and a drone would recognize the presence of birds, write its own flight path, scurry up to shoo away the intruders and then return to a charging station — without a paid person standing guard.

A software designer worked part-time throughout 2019 on the technological hurdles associated with automating the drones. Karkee had some plans to test it in 2020 but is unsure how the coronavirus restrictions will affect his work.

Besides, rules would have to change for growers to use it.

“That depends on a lot of other aspects, including the regulatory framework,” Karkee said.

Automation would be ideal, agreed Catherine Lindell, an ornithologist at Michigan State University who also tested drones as a bird deterrent. Her limited 2018 trials in sweet cherry orchards were inconclusive. “Sometimes pest bird numbers in sweet cherry orchards appeared lower in the presence of drones, and sometimes they were not,” Lindell said.

Commercial companies such as Bird-X, Flock Free and RoBird already offer a variety of drone bird deterrence methods. Some boast of drones that mimic flights and sounds of predators, with the automation that Karkee idealizes. Some are painted and shaped like falcons.

And looks may help, according to research that recently determined airplane-shaped drones, which look more like birds of prey, increased the perception of threat among blackbirds over rotor-style drones, according to a March article in “The Condor,” the academic journal of the American Ornithological Society.

“Blackbirds became alert earlier (by 13.7 seconds), alarm-called more frequently (by a factor of 12), returned to forage later (by a factor of 4.7), and increased vigilance (by a factor of 1.3) in response to the predator model compared with the multirotor,” the authors wrote in their abstract.

“Making drones as ‘predator-like’ as possible likely will reduce the likelihood of habituation,” said Lindell, who was not one of the authors. •

—by Ross Courtney

Related:

—Battling birds with lights, sounds — Video

—Sugar sours birds on eating valuable cherry crops

Luv the headline on drone article!! Question- did the blueberries flee as much or more than the birds!! Good chuckle. Thanks- really needed that today!!