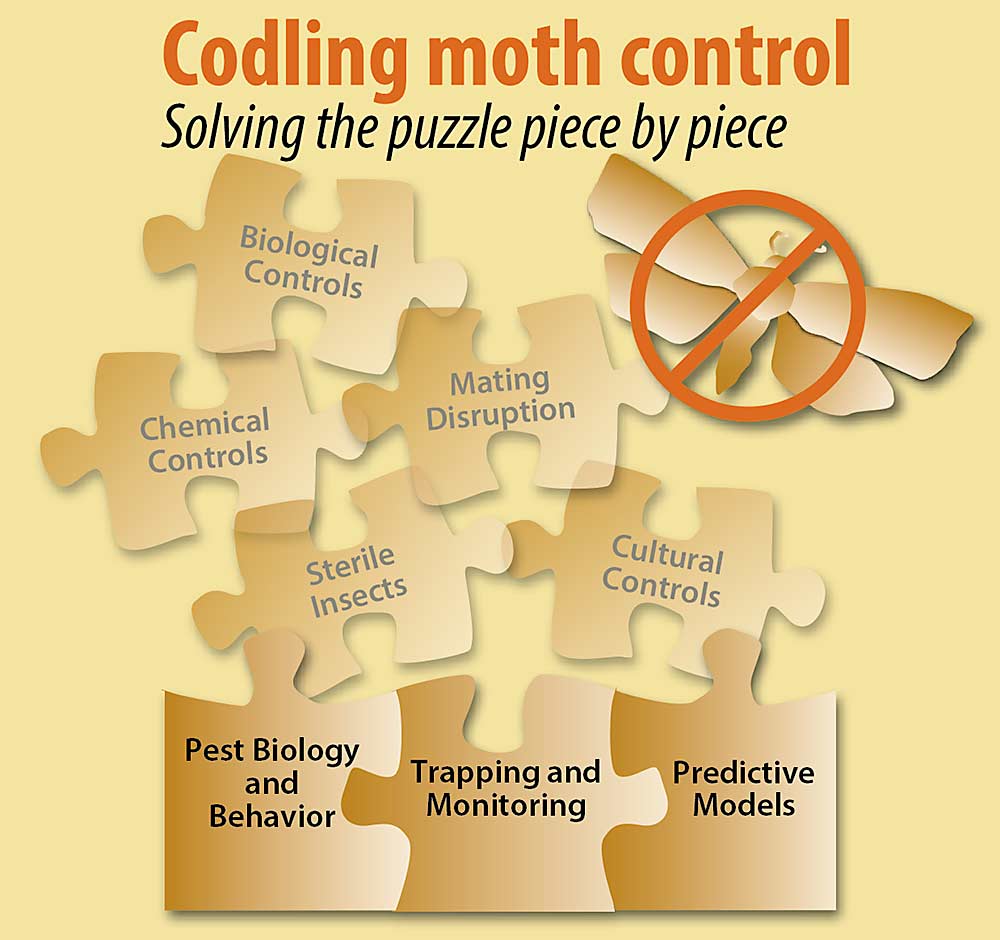

Successful codling moth control results from growers and pest consultants putting together many pieces. The leaders of a recently formed codling moth task force believe that understanding this big picture of how different aspects of the codling moth program fit together and influence each other is critical to successful IPM programs.

Some pieces, such as understanding pest biology and monitoring to assess pest pressure in individual orchards, provide the foundation upon which the rest of the control is built.

As Good Fruit Grower rolls out more coverage of the Codling Moth Summit and other stories on this topic, we hope using this piece-of-the-puzzle framework helps to show our readers how it’s all connected.

Phenology models aren’t perfect, but they work. Focus on knocking down the first generation. And don’t stop trapping.

A cadre of pest management experts drove home core biological tenets of codling moth control in late February to kick off a daylong webinar dubbed the Codling Moth Summit.

Entomologists, extension specialists and pest consultants have been looking for ways to address reports of growing pressure from — and increasing questions about — the codling moth, a key apple and pear industry pest that some in the industry had assumed was straightforward to manage after decades of pheromone disruption. Last year, those experts formed a task force to figure out where the problems are coming from and how to meet them.

One way, they decided, is to double down on biology. So, they named the opening session of the Codling Moth Summit “The Foundation.”

“Because codling moth has been researched and studied in depth for so many years, it’s really challenging to know and remember all the details,” said Gwen Hoheisel, a tree fruit extension specialist at Washington State University. Also, new people have entered the industry.

So, welcome to your first codling moth class. Speakers covered the biology of the codling moth, the intersection of phenology models and population dynamics and stressed the importance of early sprays and trapping.

Biology

Codling moth is an internal feeder pest that evolved with wild pome fruit in the mountains of Central Asia. It came to North America with European settlers and moved west with them as they planted small orchards at their new homes, said Peter McGhee of Pacific Biocontrol Corp. in Corvallis, Oregon.

The moth likes apples, pears, quince and apricots.

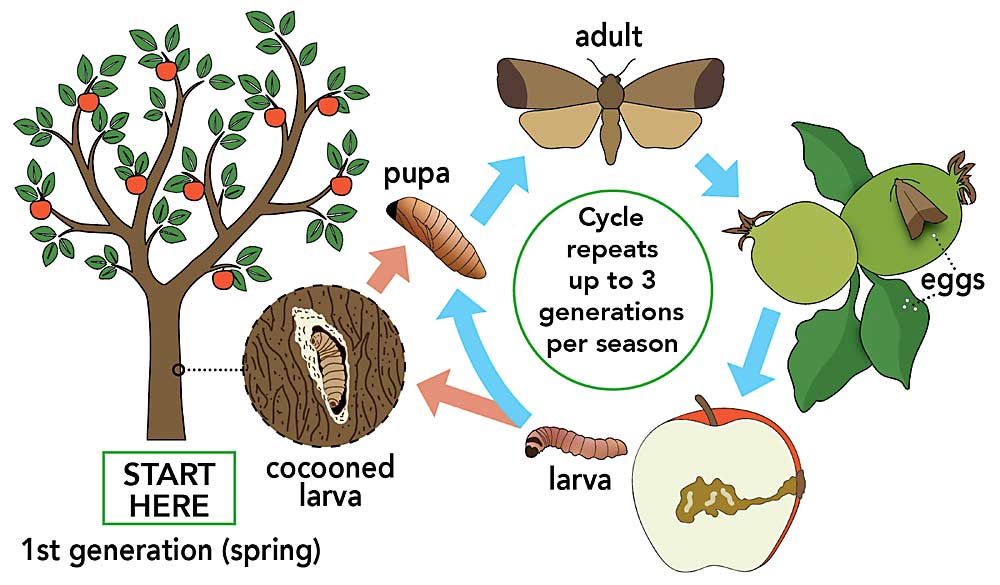

The pest goes through four life stages — egg, larvae, pupae and adult — and in the Northwest produces two to three overlapping generations per year, he said. The fruit damage comes after the eggs, which females lay under leaves or directly on fruit, hatch and larvae burrow straight to the core to feed on seeds, rendering the fruit unmarketable.

They are “opportunistic,” overwintering in fruit bins, under orchard floor debris and in crevices in the trunk, McGhee said. Trunk banding is a way to catch them and physically remove them before they fly in the spring.

Adults are not active below 58 degrees Fahrenheit, after 0.1 inch of rain or when wind is stronger than 3 miles per hour. Adults are most active from sunset to midnight, while females lay most of their eggs from 3 to 7 p.m., McGhee said.

Codling moth larvae look like oriental fruit moth, which has similar feeding activity but different timing. If growers get wormy fruit in the midst of their mating disruption programs, they may have oriental fruit moth.

“It would be imperative to identify the larvae,” McGhee said in a follow-up interview.

Oriental fruit moth larvae have a black comb on their posterior, visible with a hand-held lens. Codling moth larvae do not.

Models vs. population dynamics

Over the years, researchers have devised models that are based on codling moth phenology and give growers a rough idea when the pest will begin to emerge in the spring — the best time to spray for them.

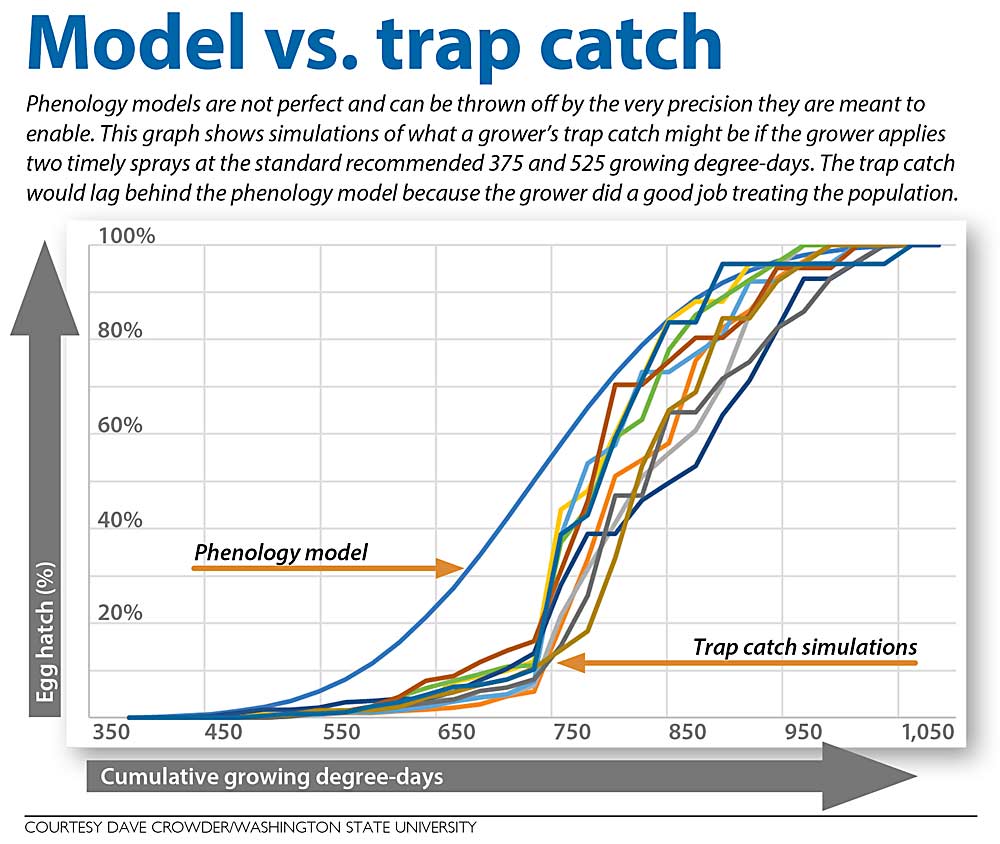

But “models aren’t perfect,” said Dave Crowder, a Washington State University entomologist and director of WSU’s Decision Aid System, or DAS, an online phenology tracking tool.

More accurately, phenology models aren’t population dynamics, a mathematical study of how a population grows, declines, shifts and ages over time. Growers track that from their trapping, giving them actual historical data for their own blocks.

“I think this is where a lot of folks get tripped up,” Crowder said.

Both provide critical information.

Models give a window of time (accurate to within seven days before or after) based on tracking accumulated heat in generalized locations throughout the Northwest. Codling moths lay their first eggs at about 375 growing degree-days, for example.

But models can’t predict when moths will emerge in every orchard because even the most sophisticated weather devices can’t measure temperature under a piece of bark where the moth is hiding. Localized rain or wind also may prevent mating flights and throw off models.

Even growers’ own management may skew things. If they spray at the right time, they will kill a chunk of the population, which then won’t show up in their traps.

Early sprays are the best sprays

Most speakers stressed the importance of nailing the first-generation spray, which allows growers to knock down a chunk of the population before it increases as the weather warms.

Codling moths overwinter in cocoons hidden in tree bark crevices or under leaves on the orchard floor. The generation that emerges in the spring is considered the first generation. That’s the one to target, said Jill Tonne, a crop consultant from Nutrien Ag Solutions.

“The most economical way to attack codling moth is to start with your first-generation spray,” Tonne said.

That’s old advice, she said, but sometimes growers try to save money by either skipping the first-generation spray or skimping on it, especially when they think pressure is low. Don’t do that, she cautioned.

Spray thoroughly with at least 100 gallons per acre, all the way to the end of rows, she said. Then, give the block a “border wrap” spray, shutting off the opposite side of the spray boom to avoid off-target spray. The foundational first-generation spray will save money later in the year.

Tonne also advised diligent pest scouting and talking to neighbors who may have backyard trees.

“Trapping is fun!”

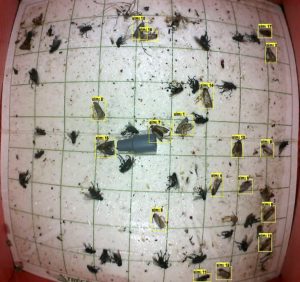

Chris Adams, an entomologist at Oregon State University, urged growers not to cut corners on trapping, either.

“Trapping is really the foundation of IPM,” said Adams, chair of the codling moth task force. Trapping allows growers to confirm model predictions, inform accurate spray timing, estimate size of later generations and detect patterns in the population.

Entomologists recommend placing one trap every 2.5 acres in both the interior and edges of blocks, in the top one-third of the tree canopy. Avoid hanging them just downwind of aerosol emitters, which will throw off trap counts.

Adams urged growers to trap even with low pressure. An empty trap is still useful data, he said, helping growers reduce the use of expensive chemical sprays through precision. Cutting just one spray every three years would pay that back.

To drive home his point, he shared an old picture of the late Larry Gut, veteran Michigan State University entomologist who died last year, checking a triangle-shaped trap with his son Tommy, as if on a family picnic. The caption read: “Trapping is fun!”

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment