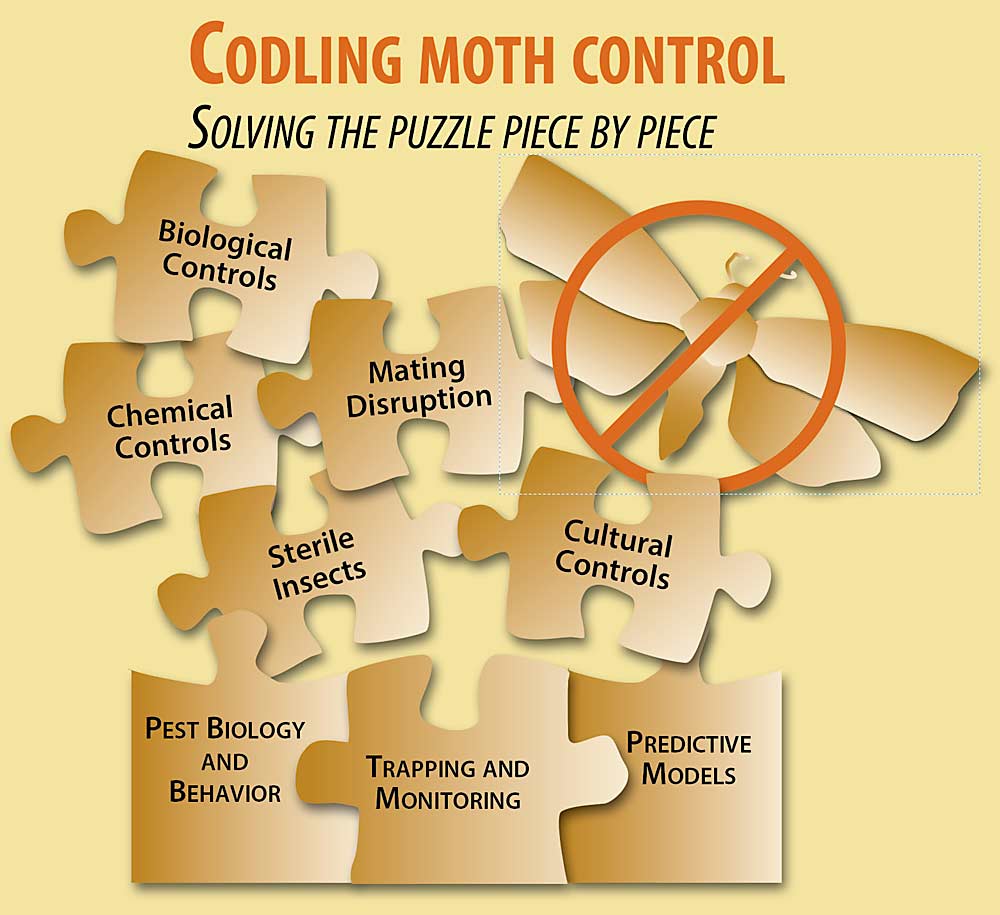

Successful codling moth control results from growers and pest consultants putting together many pieces. The leaders of a recently formed codling moth task force believe that understanding this big picture of how different aspects of the codling moth program fit together and influence each other is critical to successful IPM programs.

Some pieces, such as understanding pest biology and monitoring to assess pest pressure in individual orchards, provide the foundation upon which the rest of the control is built.

As Good Fruit Grower rolls out more coverage of the Codling Moth Summit and other stories on this topic, we hope using this piece-of-the-puzzle framework helps to show our readers how it’s all connected.

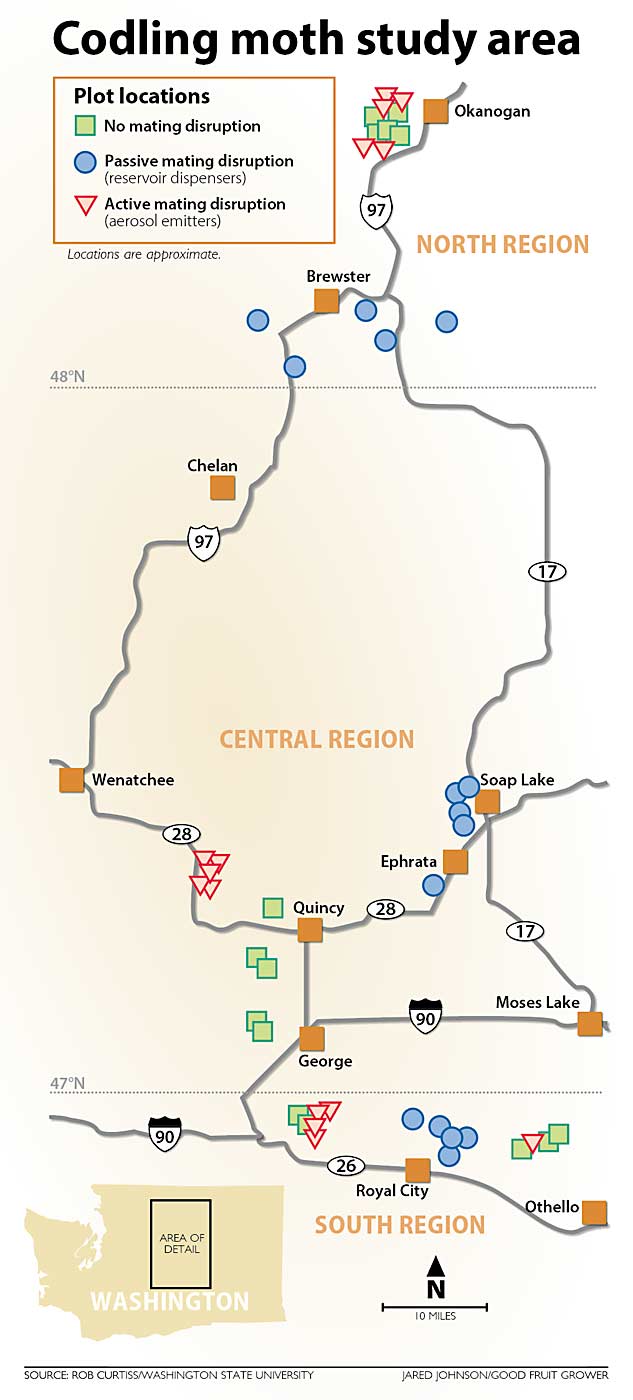

Rob Curtiss covers a lot of ground with his latest codling moth research project — 45 commercial trial sites across some 6,500 square miles of Central Washington.

“Yeah, this is a big project, but it kind of has to be,” said Curtiss, a postdoctoral research associate at Washington State University.

After all, he’s asking a lot of questions about codling moth, one of the apple industry’s top insect foes. How does mating disruption affect spray thresholds? How many lures per acre do growers need? What does trapped moth count say about pest density? And how does all of that change over different latitudes?

Though he has not yet crunched numbers, Curtiss has wrapped up the first season of data collection in his attempt to quantify codling moth movement in the modern era. Many ideas about treatment date back to the days before mating disruption was widespread and growers had only one lure to choose from.

“A lot has changed, because now we have about 10 different lures available and there’s multiple different kinds of mating disruptions,” Curtiss said. “That original threshold based on this lure with no mating disruption may no longer be accurate.”

The Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission thought it was time for some new information. If fully funded, the project will cost nearly $600,000 over three years, a cost largely due to the high price of sterilized moths, imported from a rearing facility in Osoyoos, British Columbia.

In the past few years, a resurgence of codling moth concerns in the Northwest has launched a renaissance in the corresponding science. A Washington and Oregon task force held virtual summits throughout the spring and is now conducting surveys about management programs. The research commission put codling moth at the top of its priority list for 2022.

Growers hope Curtiss’ project yields clear recommendations regarding traps per acre, pest-density estimations and efficient combinations of disruption and lures.

“My hope is, at the end of this project, the industry will have practical guidelines and an economic cost based on specific management information,” said Teah Smith, a research commissioner and also an entomologist and consultant for Zirkle Fruit.

Currently, growers rely on growing degree-day models from WSU’s Decision Aid System, compiled from research that did not factor in the mating disruption that is now widespread in the industry. Most suggestions that do take mating disruption into account come from companies that provide emitters, traps and lures, Smith said. Curtiss’ work may validate some of those.

Meanwhile, tools have changed over the years.

“We are not looking for demonstration trials,” the priorities document said. “We request replicated controlled studies and research that provides statistically significant paths forward for pest management.”

“We used to use a lure that only attracted males,” Smith said. “Now there are lures that attract males and females, and even attract at a higher rate than other lures. What does this mean for our threshold to spray now?”

Growers today also have fewer options for sprays than in the past, said Keith Veselka, a research commissioner and co-owner of NWFM, a Central Washington farm management company with blocks throughout Central Washington.

“You’re fighting the same battle with the same weapons, and maybe they’re not as effective,” he said.

A wide swath

To measure codling moth behavior and tie it to treatment thresholds, Curtiss had to fan out far across Central Washington.

Curtiss, under the direction of WSU entomologist Louis Nottingham, selected 45 commercial trial blocks of at least 10 acres each across three different latitudes. Overall, he is testing five different lures under three different mating disruption programs: active aerosol emitters, passive reservoir dispensers and no mating disruption at all. The lures in this trial are CM L2, CM 10X, CMDA, CMDA+AA and Megalure 4K, all made by Trécé.

In each block, he places four traps in the center, then releases sterilized moths at staggered distances in all directions. Though the irradiated moths have an internal dye, he and research technician Toriani Kent also dust them with DayGlo fluorescent powder, similar to the kind used in nighttime color runs — blue for 20 meters, pink for 40, green for 60 and orange for 80.

“The layout of this experiment will tell us if mating disruption is interfering with their movement and attraction to the different lures that we’re testing,” he said.

The studies should yield four important points:

—The distance moths disperse under certain mating disruption programs.

—The area across which lure plumes attract.

—The area across which a baited trap in the lure and mating disruption combination can be used to monitor moths.

—An interpretation of moth capture. That is, extrapolating what one moth in a trap tells farmers about the density in their orchards, information upon which they will base their treatment plans.

“Knowing on-farm population densities will inform decision making and should lead to better codling moth control,” Curtiss said.

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment