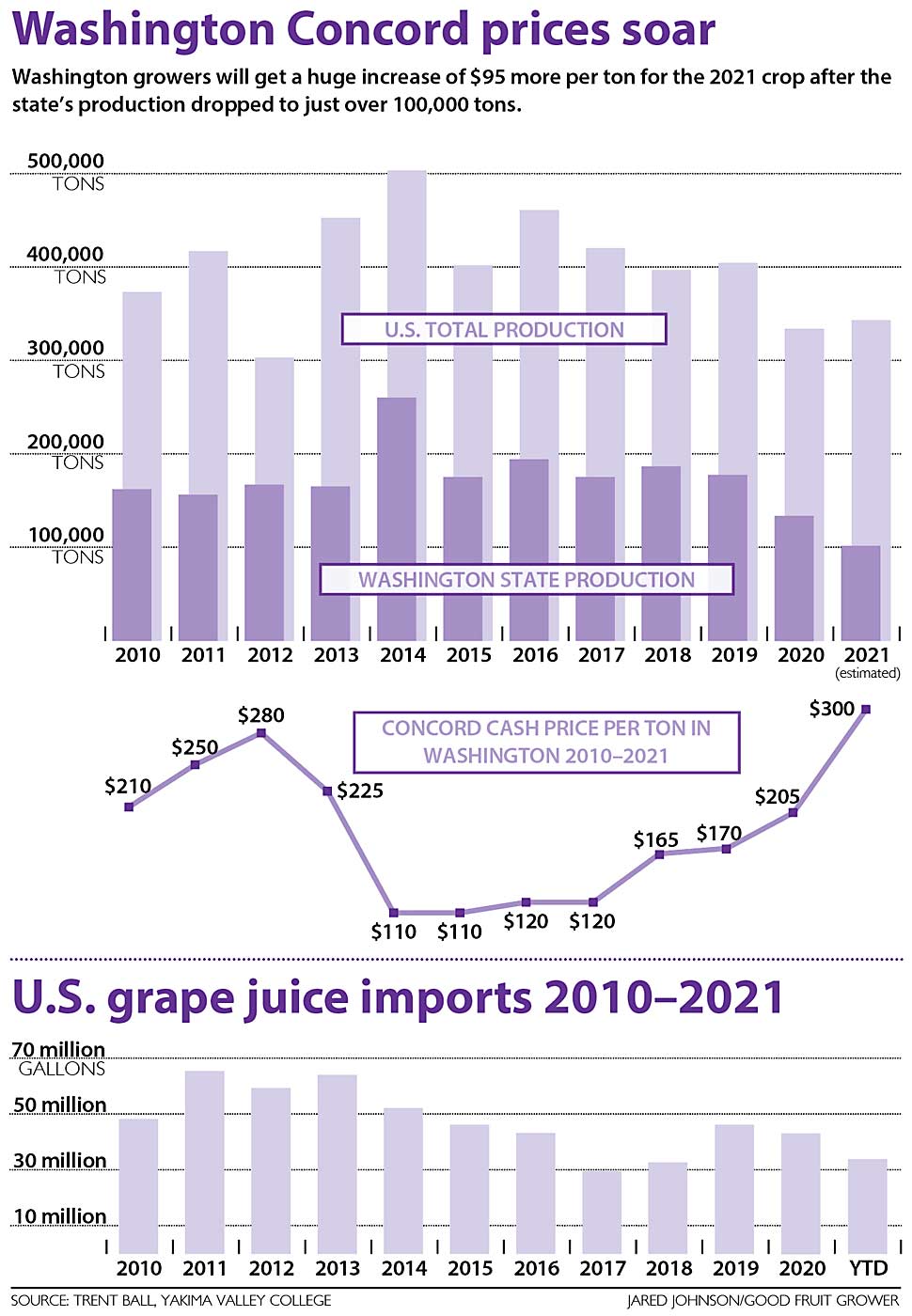

A combination of reduced acreage, low yields, low inventories and low imports pushed the cash price for Washington Concord grapes up to $300 per ton — a record high following years of prices at or under $200.

“The portrait that is painting: We are expecting prices to stay high,” at least in the short term, said Trent Ball, the industry’s unofficial economist, during the Washington State Grape Society’s annual meeting in November.

Graphic: Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower)

Ball, the director of the vineyard and winery technology program at Yakima Valley College, broke down how supply and demand have played out for the U.S. juice grape industry over the past several years, resulting in the sudden price boost.

Both the Eastern and Western production regions harvested short crops in 2020, he said, down about 20 percent from the 10-year average. For its part, Washington harvested the lowest volume since the mid-’90s, at 135,000 tons. That low 2020 inventory began to boost prices, which rose from $170 per ton in 2019 to $205 in 2020, Ball said. In the East, prices rebounded more significantly, to near $300 per ton in 2020.

Then, weather defined the 2021 season: frosts in Michigan; heat in Washington; and a wet, warm fall in New York and Pennsylvania that drove down Brix as it boosted yield.

East

The Lake Erie region, which encompasses about 30,000 acres of juice grapes in New York and Pennsylvania, harvested a record-setting crop in 2021, said Kevin Martin of Penn State Extension. Rain increased berry size after crop estimates were made, boosting an expected 200,000-ton harvest over 215,000 tons, he said, and harvest stretched into mid-November as processors scrambled for capacity to handle it all. The 10-year average for the region is 187,00 tons.

“Overall, this was a very large crop combined with what we assume is going to be a very good price. That doesn’t happen very often,” he said. “We had a lot of weather-related disasters, though.”

Some vineyards, for example, had such heavy crop loads that fruit failed to ripen.

Prices started rising in 2020, as the pandemic pushed up the demand for juice, Martin said.

“Folks are expecting higher prices,” he said. “National Grape, which drives the industry, looks like they are going to pay $400.”

The increasing price is welcome news, as costs of labor and major inputs have risen dramatically, and, after years of low prices, many growers face a backlog of deferred investment in things such as equipment. Also, the labor shortage in the region is so severe that several large grape growers are turning to H-2A for the first time.

“Next year we will have 20 H-2A workers in the region, which is up from zero three years ago,” Martin said. “We are just now getting the prices to justify that.”

With demand for fruit high, he expects prices to stay strong in the near term.

“In any other year, there would have been more fruit cut out of the market,” because of the record production and processing capacity limits, Martin said. “This year, they (processors) were willing to ship it to Michigan without concentrating it because they know they can sell it.”

West

Weather had the opposite effect on Washington’s yields.

“In Washington, we had a little bit of the flip side. It was a high-heat year, which led to small berries,” Ball said. “It’s more wine-grape-like than Concord-like.”

As a result, Washington yields were historically low: 6.3 tons per acre on average, compared to the 20-year average of 8.8 tons per acre. Growers harvested just 103,000 tons from 16,300 acres, Ball said.

Those are the numbers that give Concord growers optimism, said Art den Hoed, a Sunnyside, Washington, grape and tree fruit grower who also serves on the society’s board.

“There’s more optimism because things are headed in the right direction,” he said. “Of course, production was awful light this year, that’s part of it, but hopefully high prices will stay around because a lot of Concords have come out. Concord juice has a stable market now, but it wasn’t too many years ago Welch’s was paying people to pull out.”

In 2014, when prices crashed amid oversupply, growers in Washington had over 21,000 acres in juice grape production. After several years of steady declines, removals seem to be slowing. The 16,300 acres harvested in 2021 is down from 16,600 in 2020.

Den Hoed said he doesn’t expect to see that grow very much. Planting new vineyards is an expensive proposition, even at $300-per-ton returns. He expects to see some new plantings “on good Concord ground” — where it’s a little too cold to support higher-value fruit such as cherries, apples or wine grapes — or see folks replanting aging blocks, but nothing dramatic. Growers have seen the damage oversupply delivers, he said, and will be cautious.

But he hopes the higher prices might encourage younger farmers to consider Concords.

“The Concord grape industry as a whole is older people, and to get young people involved and planting grapes, they have to see that if you can make money at it, it’s a good deal,” den Hoed said. “The biggest thing with Concords is once you get them up, you can do almost everything mechanical,” and in the increasingly expensive labor market, that might have increasing appeal.

Ball said he expects the high prices will probably spur an increase in production, but not enough to fill the void that currently exists.

“This is a very cyclical industry; when you see the ups, you see the downturn,” Ball said. But in the U.S. market, “we are never going to see 500,000 tons again, maybe not 400,000 tons, with all the acreage that has come out. Maybe we are stabilizing the market and won’t see as significant of swings.”

Another factor Ball cited that’s likely to keep prices up: Imports just can’t get in. South American grape producers would like to sell their juice, but constrictions in global trade leave little room for low-cost concentrate. Of course, supply chain snarls also challenge U.S. processors and growers, Martin added.

“High prices for concentrate can drive customers to look for alternatives, but there are no alternatives this year,” Ball said. “With low inventory going into the season, low production overall, a lack of product coming in and COVID really increasing the demand for buying juice, which is a good thing and a positive sign for the industry … cash price is likely to stay high (next year) unless something dramatic changes between now and then.”

—by Kate Prengaman

Longtime leaders honored

The Washington State Grape Society honored two longtime leaders during its annual meeting.

Society President Catherine Jones presented the Lloyd H. Porter Grower of the Year award to Edward Crawford of Prosser.

“He and his family were, along with others, pioneers in turning many acres of sand and sage into valuable farmland, in what would become the Roza Irrigation District,” Jones said. “Ed has been a fixture on the Roza since the beginning. Those who know him know him to be a tireless worker and an exceptional neighbor.”

Crawford planted his first Concords in the 1960s and his first wine grapes, Riesling, in the mid-’70s. Through the years, he always opened his farm to Washington State University research trials, Jones said.

She also presented the Walter Clore Award, posthumously, to Albert Don, who served as the vineyard operations manager at Wyckoff Farms for over 30 years. The award recognizes individuals for their service and contributions to the Washington state grape industy.

“He always wanted to make things easier, faster and find a better way to do things across the farm. He was always willing to share his ideas and learn from others at the same time,” Jones said. “His son, Jason, said that to him, Albert’s legacy is if you work hard, stay dedicated and be humble in your life, you can do anything that you put your mind to.”

Jason Don accepted the award on behalf of his father, who died unexpectedly in February. He said that if his dad were here to accept the honor himself, he would be at a loss for words, except to say that he shared the achievement with everyone on the Wyckoff vineyard team.

—K. Prengaman

Leave A Comment