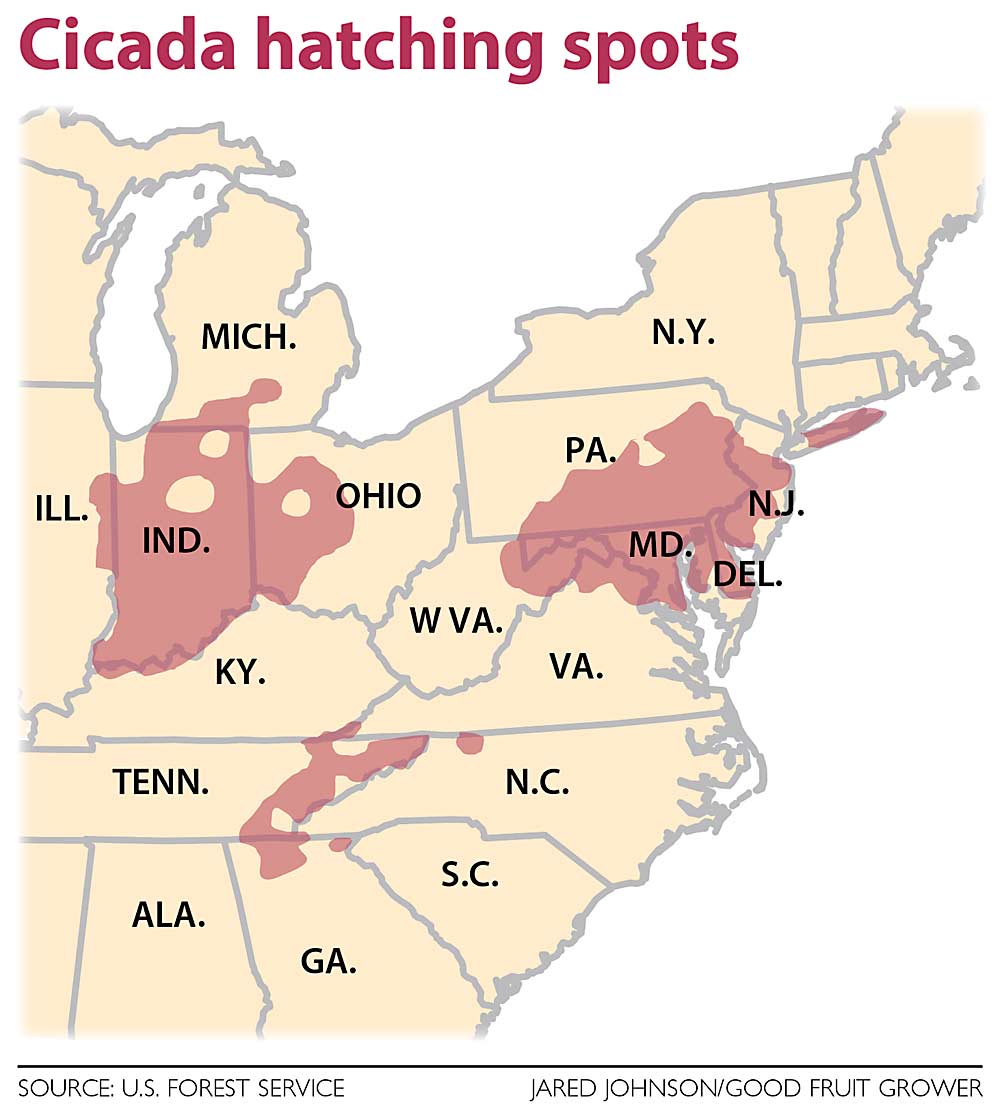

For the first time in 17 years, billions of cicadas are emerging from the ground across a wide swath of the Eastern United States — climbing, molting, mating, laying eggs, dying and generally making a massive nuisance of themselves.

They also might be damaging young fruit trees and grapevines.

This particular group of cicadas — known as Brood X — climbs to the surface when the soil reaches about 64 degrees Fahrenheit (so, any day now, if it hasn’t happened already). The adults will live for about a month. Their eggs will hatch a few weeks later and the nymphs will go underground. They won’t re-emerge until 2038, according to Elizabeth Long, an assistant professor of entomology at Purdue University.

Good Fruit Grower interviewed growers and others in the fruit industry in Brood X hot spots in the Mid-Atlantic and Midwest in early April, before the cicadas started to emerge. Most of them remembered the previous emergence in 2004, and some memories went back even further. They were anticipating some damage to young fruit trees and were taking precautionary measures, but no one was expecting a horticultural or viticultural catastrophe. Their real concern was the sheer ubiquity of Brood X cicadas blanketing every surface, vertical and horizontal, for a few weeks, and their mating calls making a deafening racket.

“It’s just crazy,” said Phil Baugher, president of Adams County Nursery in Aspers, Pennsylvania.

David Byers, an orchardist in Bedford, Indiana, said the same thing.

“It really gets bad,” he said. “We get so tired of it, but we can’t do anything about it.”

Tree damage

Once aboveground, Brood X females lay eggs in more than 200 woody tree species, including apple, cherry, peach and plum, and in grapevines. They cut slits in the bark with their ovipositors and lay their eggs inside. This process physically weakens the branches, which could turn brown and die. Young trees with branches between 3/16 and 7/16 of an inch in diameter are the most susceptible to damage, Long said.

Greg Krawczyk, a tree fruit entomologist with Penn State University, said there are no insecticides specifically registered for Brood X cicadas, but a number of broad-spectrum products should be effective at mitigating their impact. Additional applications of such products could hurt beneficial insects, however, causing increased pressure from secondary pests.

Another protective measure, netting young trees, might work well for homeowners and gardeners but is impractical for commercial orchards, Krawczyk said.

University of Maryland Extension entomology specialist Stanton Gill said cicadas mainly dwell in wooded areas. They’re not strong flyers, so most damage will be done to trees on orchard edges near woods. Growers will use Danitol (fenpropathrin) to knock down cicadas if they see them, he said.

Maryland is ground zero for Brood X’s emergence, but the brood doesn’t pose a severe threat to the state’s orchard industry. Most growers will keep a close watch and spray as needed, then remove damaged branches over winter, said Bryan Butler, a UMD principal extension agent.

“It seems like a very exciting story for everyone to get worked up over, but it scares me less than a resurgence in BMSB, because at least we know this is coming and when it will begin and end,” he said.

Maryland grower Robert Black, 69, has experienced Brood X before. He said it’s just one of many challenges he’s learned to deal with as a fruit grower. The cicadas damaged some of his trees back in 2004, but it was manageable. He planted new trees earlier this spring, same as normal.

Black said extra spraying is the only real way to deal with the cicadas, and even then it’s hard to keep up because they just keep coming out of the ground. He might have to spray at five-day intervals, instead of seven or 10, and maybe do some extra pruning later in the season.

“It’s on my mind, but I think we’ll be OK,” he said.

Baugher said Brood X damaged some of Adams County Nursery’s young trees in 1970 and 1987, but most of its trees are in Delaware now, where good nursery land is easier to find — and which has the added bonus of not being a Brood X hot spot. He anticipates some cicada injuries in the pear nursery, which is still in Pennsylvania, but they’ll deal with that by pruning the limbs below the injuries and starting new leaders.

In south-central Indiana, another cicada hot spot, Byers, 84, has seen Brood X emerge a few times. His fruit trees are all more than 20 years old, so he anticipates egg-laying damage to be minimal.

“All you can do is spray them, or live with them, or both,” he said.

Maryland grower Washington White decided not to plant new trees this spring. Brood X wasn’t a major problem for his orchard back in 2004, but he’d rather avoid damage to young trees if he can help it. He can’t afford to net every tree, and he’s not sure spraying will accomplish much, he said. Mostly, he’s just hoping for the best. Freeze and hail events have made the past couple of years “terrible.”

“And now the cicadas are coming,” he said with a chuckle. •

—by Matt Milkovich

Leave A Comment