With rolling orchard topography in the background, Cornell University researcher Terence Robinson speaks about soil variability with Andrew Wright of Helena Agri-Enterprises, right, and Bob La Comb of Fowler Farms in February in Rochester, New York. (Ross Courtney/Good Fruit Grower)

Soil is never uniform throughout an orchard. Each hill and dale has different depths and chemical makeups. Some parts might lack calcium; others have plenty.

A Cornell University researcher is urging growers to map the soils in their orchard blocks to overcome this variability and thus deliver nutrients more precisely.

“Identify the variability in the soils and then do something about it,” Terence Robinson told tourgoers at the February annual meeting of the International Fruit Tree Association in Rochester, New York.

Robinson has been working with Fowler Farms and Helena Agri-Enterprises on a nutrient variability project for five years.

On a 30-acre block, Helena used a Veris Technologies machine that measures electrical conductivity of the soil to create a georeferenced map of soil variability. From that map, the company identified and mapped management zones, then collected soil samples from points suggested by the machine’s GPS to determine exact nutrient loads.

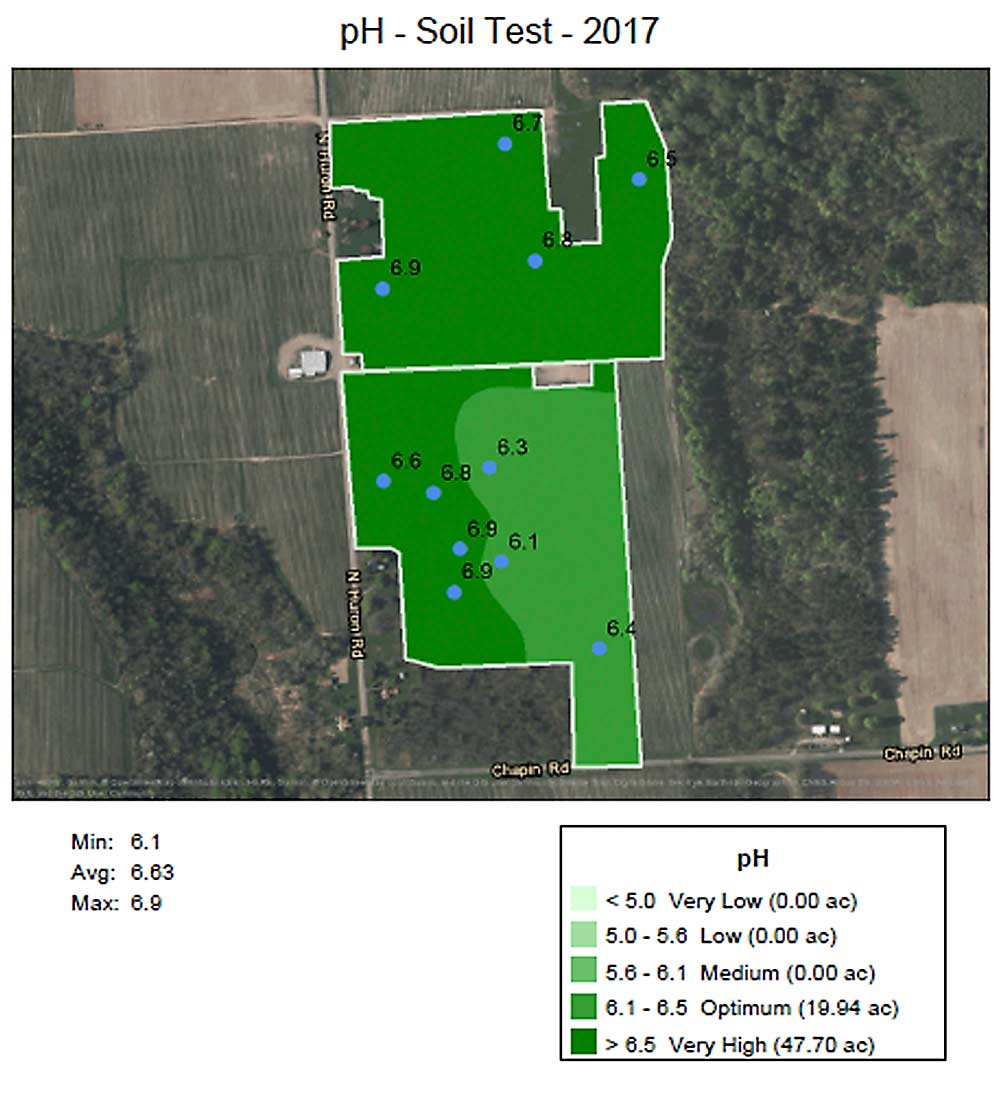

The end result was a computerized map of the various soil needs of different sections of the block.

For example, Helena turned the information into a recommendation map for lime. Some spots in the block needed 400 pounds per acre. Others called for 13 times that amount — 5,200 pounds per acre. Trying to average those rates would have grossly under- or over-fertilized various spots.

A recommendation map of a 30-acre Fowler Farms apple block calls for lime at wildly disparate rates. (Courtesy Helena Agri-Enterprises)

To make use of the information, Fowler Farms has applied different rates of lime, nitrogen and potassium using a variable rate fertilizer spreader to try to even out these three nutrients across their orchards.

The company has since begun variable rate fertilization on other orchard blocks, said Bob La Comb, a horticulturist for Fowler Farms. Results are not definitive, but anecdotally, he has noticed some improvement. Yields seemed to increase by roughly a bin per acre in a block of six different varieties three years in.

“We’re still really early in the game,” he said.

To explore results further, Robinson and his Cornell colleague, Lailiang Cheng, have been collecting Honeycrisp apples from the block and measuring their nutrient content. They hope they can help Fowler Farms produce apples with, say, a uniform ratio of calcium to potassium, both of which affect fruit size, bitter pit and biennial bearing.

Machinery such as Helena’s makes things easier, but growers don’t necessarily need the mechanization to do this, Robinson said. They could simply lay a grid through the orchard ground, pull soil samples and draw their own soil maps.

The trick is to use a dense soil sample pattern, he said, to finely track variability. Cornell researchers have suggested this before, Robinson said, but the idea never took off until mechanized and computerized tools, such as those from Helena, made the chore easier.

In the end, Robinson hopes that more precisely delivering nutrients to the parts of an orchard block that need it will lead to better yields and higher quality, and therefore more money. Does it work?

“I don’t know the answer to that yet,” Robinson said. “I hope it does.” •

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment