In the last two decades, Michigan has gone from being the dominant force in the U.S. blueberry industry to being just another blueberry region. Increased supplies of fresh and frozen blueberries have depressed prices, and no relief can be expected if current market pressures continue, said Mark Longstroth, a small fruit educator with Michigan State University.

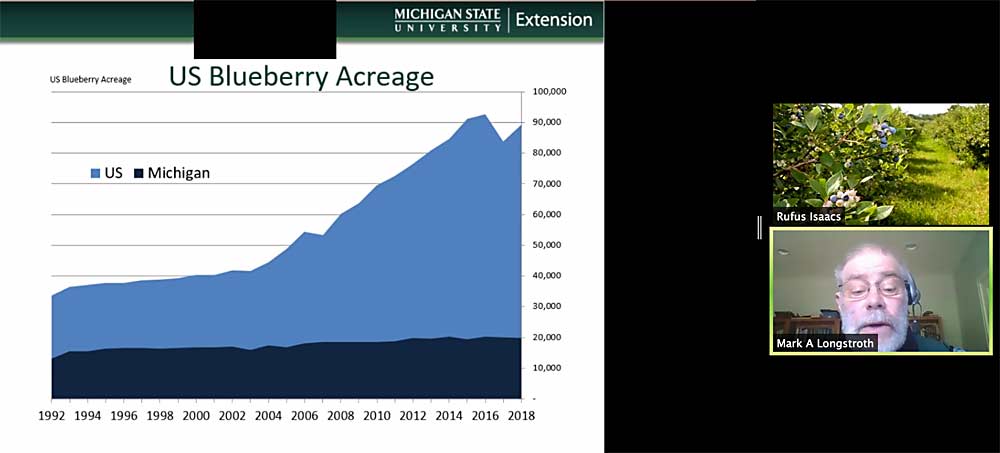

In his virtual talk, “Restoring Michigan Blueberries,” during Day 2 of the Great Lakes Fruit, Vegetable and Farm Market EXPO, Longstroth said that while Michigan blueberry acreage has increased from 15,000 to 21,700 acres since 1992, overall U.S. acreage has increased from 33,000 to more than 89,000 acres. Michigan went from producing more than half of the total U.S. crop in 1993 to producing about 12 percent in 2018.

“As time goes on, (Michigan) becomes less and less important,” he said.

Most of the country’s blueberry growth has come from the Pacific Northwest, where Washington and Oregon are now the dominant producers. British Columbia has grown significantly, too. Production in these newer regions is also more efficient than in Michigan. Where Michigan produces about 4,100 pounds of blueberries per acre, Oregon produces 11,700, Longstroth said.

As blueberries have become a global crop, Michigan’s traditional advantages have disappeared. Fresh and frozen berries are now available year-round. In order to compete, Michigan growers need to improve the efficiency of their farms and their industry.

He gave an example of Michigan’s inefficiency: Of the state’s 21,700 acres of blueberries in 2018, 12,300 were more than 30 years old — and many were 50 or 60 years old. Michigan is competing with 1930s varieties and 1970s technology.

“We’re competing with a Model A pickup truck against a Ford F-150,” Longstroth said.

Combine old fields with old varieties. The three most voluminous varieties in the state are Jersey (5,800 acres), released in 1928; Bluecrop (5,600 acres), released in 1952; and Elliott (4,200 acres), released in 1973, he said.

Costs have gone up at the same time. It cost $800 to grow an acre of blueberries in 1993. In 2019 — due in part to managing spotted wing drosophila — it cost $2,700.

But cost per acre is not the best way to look at the situation.

“It is not how cheaply you can grow an acre,” Longstroth said. “It is how cheaply you can produce a pound of blueberries. Money spent that increases yields increases the cost per acre, but often reduces the cost to grow a pound of blueberries.”

Growers who lower their input costs to focus on processing berries are “penny wise and pound foolish.” Cutting back on inputs increases the cost to produce a pound of blueberries, he said.

“The goal is not to maintain high volumes of Michigan blueberries, but to restore the profits of Michigan blueberry growers,” Longstroth said. “If the profit margins of growing processing blueberries are too low, get out of that market. Focus on the fresh market or develop new markets.”

Longstroth had more advice for growers looking to modernize:

—Remove unproductive fields. If they are not making money for the farm, they are costing the farm money.

—Leave the field fallow for several years, to avoid replant issues.

—Plant test plantings of many varieties to determine which best fit your market window.

—Prime new fields. Get them ready to plant and be productive.

—by Matt Milkovich

Leave A Comment