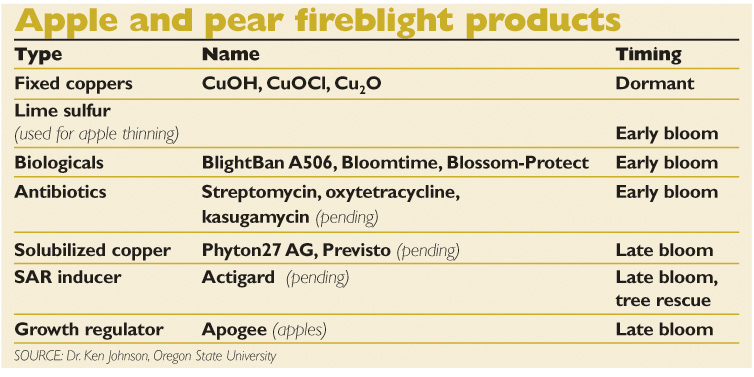

Pear and apple orchardists have a fairly broad field of products to use in controlling fireblight—and it should get even more crowded in the coming year with new registrations anticipated, says an Oregon State University plant pathologist.

Several new products have registrations pending and could be registered in 2013, said Dr. Ken Johnson, who specializes in fireblight research at OSU in Corvallis, Oregon. Kasugamycin, a new antibiotic that goes by the name Kasumin, was registered in Canada in December and is awaiting registration from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. A new solubilized copper by Gowan Company called Previsto is also pending, along with a new technology that uses the plant’s own defenses. The systemic acquired resistance inducing agent is a Syngenta product called Actigard (see “Turning on a plant’s defenses”).

With the addition of the new products, growers will have several effective materials to protect their trees from the fireblight pathogen for a longer period—from dormancy to late bloom and even possibly tree rescue treatments in summer. Predictive models also help growers to better time sprays based on disease development.

Here’s a rundown of today’s fireblight products and how they fit in an integrated control program, according to Johnson:

Fixed coppers (several products available) applied during dormancy. Research studying fixed coppers applied at delayed dormancy with dormant oils has been encouraging, Johnson said. “The coppers do have an effect in reducing the number of infected flowers at bloom,” he said. “Fixed copper is a sanitation treatment that delays the build-up of epiphytic pathogen populations.” Additionally, three years of research in collaboration with University of California’s Rachel Elkins found no difference in russeting and fruit finish from the copper applications compared to dormant oils.

“This is some of the first data I’ve seen that shows that coppers can have an effect,” Johnson said during a session at the Washington State Horticultural Association’s annual meeting. The research involved applying six pounds of active ingredient per acre at delayed dormancy in late March in California. Researchers used molecular scouting to detect the pathogen. Growers applied a full antibiotic program during the mid- to late-bloom period.

“Initially, we couldn’t find fireblight in the early bloom, but as we moved to late petal fall, in the blocks where we didn’t spray the copper, 100 percent of the flowers sampled were infected,” he said. “Where we put the coppers on, infection was delayed, and we saw 30 and 60 percent infected, depending on the year.”

Through molecular scouting of rat-tail blooms, Johnson said that researchers have learned there is more risk presentin orchards in the summer than they previously thought.

Biologicals. Three types of products are available and all are approved for organic use: bacterial stigma colonizers (BlightBan A506, Bloomtime Biological), yeast floral cup colonizer (Blossom-Protect), and an antibiotic substitute (Serenade Max, also known as Optiva). Application timing for biologicals is early bloom.

Stigma colonizers (BlightBan A506 and Bloomtime Biological) are bacteria that grow on the stigma and prevent the pathogen from growing. Both products are beneficial when applied up to full bloom, but are not much value after that, he says.

Blossom-Protect is an aggressive yeast that colonizes the stigma, flowers, and floral cup—just about everywhere, he said. Research on apples found 200 fireblight strikes per tree in the water control, and 10 strikes per tree with Blossom-Protect. “It works really well,” Johnson said, adding that he believes it will have a good fit with organic programs, especially if the use of antibiotics is prohibited as expected by the National Organic Standards Board. “We found the yeast growing all over the nectaries, making a biofilm on them. It’s a really aggressive biological agent, and it hangs around everywhere, even on the calyx in mid-June.”

However, a drawback for the yeast could be a potential for russeting in pears if there is wet weather at bloom. He has seen some russeting in OSU fireblight trials in Corvallis, but they are orchards where he also has a problem with apple scab. “I don’t think you’ll see russeting in Washington or Oregon where you don’t get apple scab,” he said, adding that Washington State University Extension educator Tim Smith has not had a problem with russet in his trials with the yeast product. “But Tim also hasn’t seen apple scab for 20 years. If you don’t get apple scab, then you probably won’t get russeting in pears from Blossom-Protect.”

Serenade Max (a new version is coming called Optiva), works as an antimicrobial compound. Johnson likens it to oxytetracycline, but says the biological has a shorter life than oxytetracycline. “It has a better fit in an organic program or as a resistance management strategy than it does as a stand-alone product,” he said. “The problem with Serenade is that you have to double-down on applications because of its short life.”

Antibiotics (streptomycin, oxytetracycline, kasugamycin), applied at early bloom. Oxytetracycline has been the bread-and-butter product in the Northwest, but it’s not a strong performer, averaging about 60 percent disease incidence in trials, and timing has be just right. However, “it’s the best thing we have,” Johnson said, although it doesn’t match up to the old days of using streptomycin, before there was resistance.

In trials comparing applications of Kasumin and oxytetracycline to streptomycin or oxytetracycline alone, Kasumin performed well, showing less than 15 percent disease incidence. To avoid the possibility of developing resistance with Kasumin, he recommends using a full rate of Kasumin with a quarter-rate of oxytetracycline.

But Kasumin has not performed as well in eastern United States, he said, adding that streptomycin has done best there in efficacy trials. “If you don’t have streptomycin resistance, it’s been the most effective antibiotic for eastern United States.”

A caveat for using Kasumin is phytotoxicity potential. Burning of the leaves has been observed a few times during residue trials on Granny Smith apples. “It’s a warning that there could be finish problems with pears,” he said.

Soluble coppers (Phyton 27AG and Previsto), intended as bloom and petal fall treatments. The new soluble coppers are safer than the old fixed coppers and have a longer residual time of seven to ten days, compared to three days from antibiotics. Other advantages are good absorption by the plant and the ability to apply at late bloom. Also, the coppers are bactericidal (bacteria-killing), whereas the antibiotics are bacteriostatic (bacteria-inhibiting).

He believes the soluble coppers may have a fit for some orchards, including organic orchards (components of the Previsto formulation have been accepted as organic). Extensive fruit finish testing of Previsto has not shown any problems.

Phyton 27AG, copper sulfate in tannic acid, is registered, though fruit finish testing has not been completed, and the product’s organic status is unknown.

The soluble coppers have shown a dose-response in research trials, and appear to give the best control of fireblight at around 96 ounces per acre.

Leave A Comment