Irrigating more, overhead cooling and shade netting.

Washington wine grape growers threw a variety of mitigation strategies at the 2021 heat wave, with varying results and trade-offs, as they tried to counter the effects of the so-called “heat dome” — a period of extreme temperatures in early summer — and an overall hot vintage with 29 days over 95 degrees and a record of 3,238 growing degree-days in Prosser.

“Grapes like warm weather but they don’t necessarily like hot weather,” said Markus Keller, a Washington State University viticulturist at the Irrigated Agriculture Research and Extension Center in Prosser.

There’s no single correct answer, of course, but a panel of three Washington growers discussed mitigation measures in November at the Washington State Grape Society annual meeting in Grandview. Keller moderated.

Here’s what they said at the meeting and in follow-up interviews with Good Fruit Grower.

Sagemoor Vineyards

Sagemoor Vineyards has used overhead sprinklers to cool canopies for years, as well as drip tape under canopies to manage deficit irrigation, said Lacey Lybeck, vineyard operations manager. The technique just came in extra handy during the 2021 heat wave.

The vineyard near Pasco, planted in a former alfalfa field, has big main lines and ponds that fuel 60-gallon-per-hour sprinkler heads, even more volume than traditional overhead cooling in apples.

During the heat wave in late June and early July, the company cycled the overhead sprinkler two to three times per day, making sure to turn it off about four hours before sunset, to prevent water from reaching clusters or the vineyard floor, Lybeck said. Within 30 minutes after a cycle, there was no evidence that irrigation had been used at all, and soil moisture profiles registered no increase in water levels. In fact, they ran the overhead sprinklers sometimes at the same time as under-canopy drip.

Lybeck’s crews measured success with thermal camera imaging and a close visual inspection of leaves, which often cupped and curled when water didn’t reach them, such as when tendrils obstructed the sprinkler heads’ oscillation.

The method is expensive, Lybeck said. Drip lines typically run $1,500 to $2,000 per acre for materials and labor to install. The high-volume, overhead system runs another $1,500 to $2,000 per acre on top of that.

The cost would pay for itself relatively quickly, she said. “But $1,500 to $2,000, that’s 1 ton of grapes.”

The company intends to continue installing both overhead sprinklers and drip irrigation in the future and hopes to use WSU research data about heat stress and mist cooling to fine-tune volume and cycle spacing, she said. Though 2021’s heat wave was rare, such events likely will become more common, Lybeck said.

“We’re kind of anticipating that more extreme summer weather is going to be part of our future,” she said.

Ste. Michelle Wine Estates

Some Horse Heaven Hills growers contracted by Ste. Michelle Wine Estates augmented irrigation in advance of the heat wave, and that seemed to do the trick, said Yun Zhang, a viticulturist for the state’s largest wine producer.

“The good thing is that clearly that worked,” Zhang said. Her guess is that the extra water enabled the vines to cool their canopies through transpiration.

Weather forecasters saw the heat wave coming, so some growers started ramping up their irrigation one or two weeks early. In the vineyards where they didn’t, Zhang found canopy damage.

Growers also did not thin leaves as intensely or lift trellis wires during the heat wave, which they often do to increase sun exposure in certain red varieties, Zhang said.

Zhang acknowledges that increasing irrigation can alter deficit irrigation goals, forcing some growers into a balancing act, she said.

None of the growers in her region used shade cloths or overhead irrigation, she said.

Olsen Bros.

On a large scale, Olsen Vineyards managed heat stress by limiting leaf thinning, reducing it on about one-quarter of their acreage and skipping the task altogether on the rest, said Leif Olsen, a partner in his family’s farm business near Benton City.

The company also irrigated extra in advance of the heat wave but ended up overdoing it on some blocks, he said. Riesling and Sauvignon Blanc ended up with botrytis and sour rot, and the vines pushed too much vegetative growth — which the company had to hedge.

Olsen also experimented with a form of shade netting on about 1 1/2 acres of Mourvedre, a high-end grape in a Benton City vineyard. Stealing the idea from another grower, he ordered just a small amount of the 2-foot-wide netting and stretched it across the west side of his fruiting zone, using bread clips to hold it in place against the trellis wires.

“It worked great,” he said. In places where he did not have it, he had to drop sun-damaged fruit to the ground. His crews typically put up protective bird nets closer to harvest anyway, so the shade netting saved a step on that side of the rows.

Olsen plans to use it again this year but not expand. The material costs up to $500 per acre, not including the labor to put it up and take it down. He only uses it on the high-value grapes. It can be cut in half lengthwise to double its coverage area, he said.

“It was very successful, but the downside was the cost,” he said.

WSU research vineyards

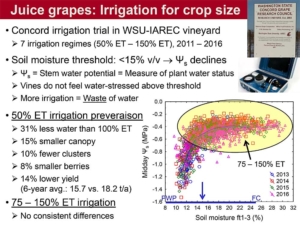

The head-scratcher in all of this is the extra irrigation, something Keller said the verdict is still out on. He knows growers use that technique and he understands the impulse: He’s just not convinced it works.

Many of the experiments by his team show grapevines — Concord or wine grapes — reach a point at which they max out on water. Any more just evaporates from the leaves into the atmosphere. That evaporation, of course, provides some evaporative cooling to the canopy, but it does not improve the vines’ overall water status.

“There’s no additional benefit of adding more water,” Keller said.

In fact, too much water will throw off deficit irrigation goals and lead to mildew problems and overgrowth, like Olsen experienced.

One trial, led in 2021 by Charles Obiero, a postdoctoral researcher on Keller’s team, involved 30 different varieties at a Roza research vineyard near Prosser. Obiero watered adequately at end of bloom and beginning of fruit set and then not again until veraison. The vines went 45 days with no water.

“And they all made it through the heat wave,” Keller said. “They didn’t seem to care.”

That doesn’t stop growers from trying, and Keller understands. The problem is that those growers typically don’t leave a block less watered for a scientific control, so data from them is anecdotal.

He advised that growers who have their minds made up to boost irrigation in the face of heat should apply water only in measured amounts that let the soil dry out between applications.

“My advice would be, if you must just because of psychological reasons, yes apply a little bit of (extra) water — but please, please, please don’t just pour the water on,” he said.

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment