Shippers are moving less fruit through Washington’s ports of Seattle and Tacoma this winter.

Part of that is due to the short apple crop — revised down to 100 million boxes as freezing weather hit the late harvest.

“When we have a crop the size of what we have this year, we could move it all domestically. We really don’t need exports,” said Steve Reinholt, export sales director for Wenatchee-based Oneonta Starr Ranch Growers, typically one of Washington’s largest apple exporters.

But Reinholt and representatives of other leading sales desks call that strategy shortsighted. The industry needs to maintain relationships with those offshore customers for the next 120- or 130-million-box crop.

“No markets are going to wait. A lot of our markets have been backfilled with Eastern European apples, Turkish apples,” said Bryan Peebles, export sales director for Chelan Fresh. “And what’s next year’s crop going to look like? Is that 140-million-box crop still out there?”

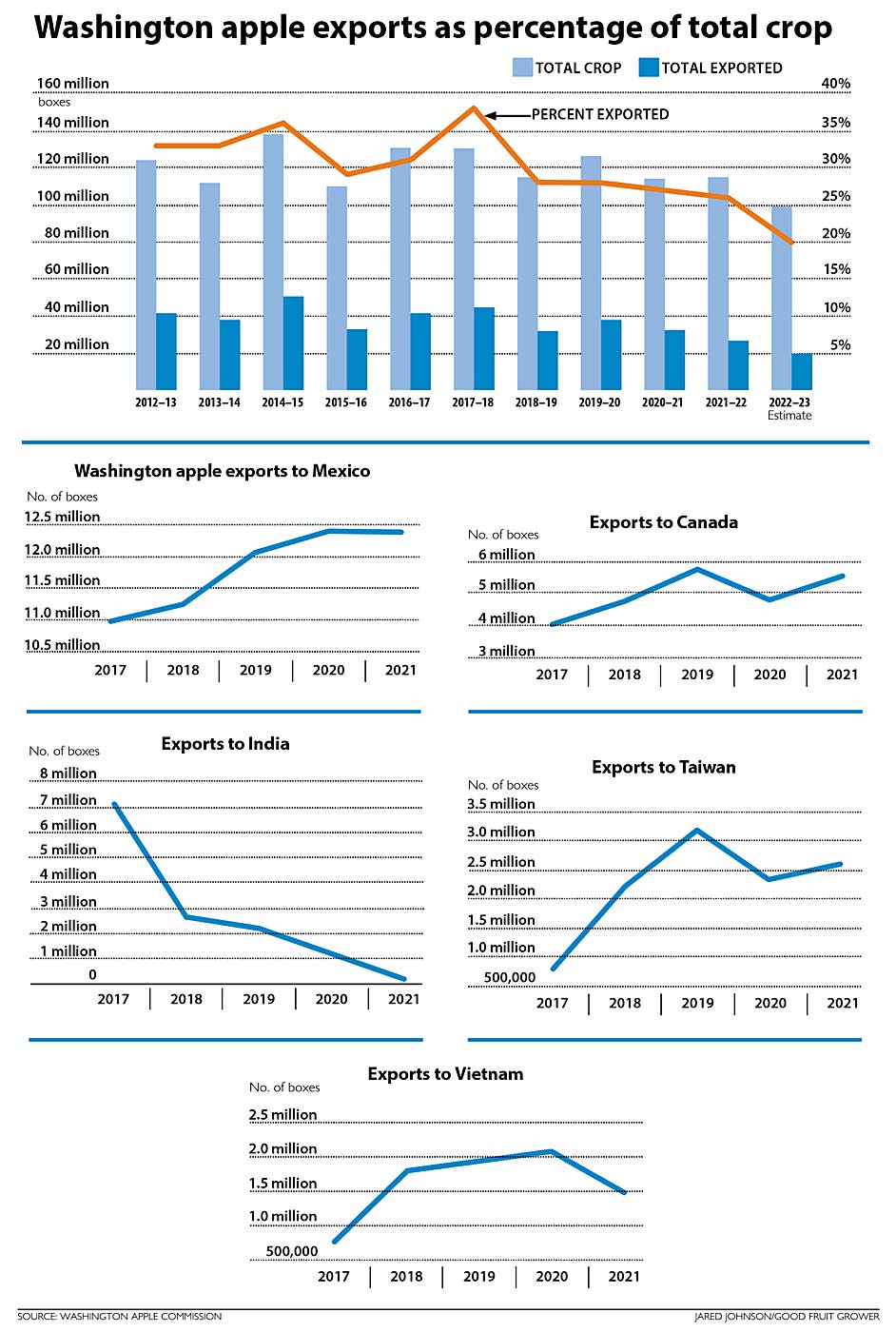

The last time Washington almost hit 140 million boxes, in 2014, 35 percent were exported. Over 7 million boxes of Red Delicious went to India alone.

That 2014 export market is gone, and shippers say it’s not coming back.

Years of tariffs tanking the Indian market. A pandemic snarling supply chains. Skyrocketing ocean freight rates. The ripple effects from a strong dollar. Growers’ ever-increasing costs of production.

Meanwhile, varietal changes and economic forces writ large and small are changing the equation for what Northwest growers need the export market to be.

So, what does the new export road map look like? Fewer Reds and more Cosmic Crisp, for sure.

In 2014, Washington exported 44 million boxes of Reds, said Todd Fryhover, president of the Washington Apple Commission. In 2022, growers harvested 13 million boxes, and the domestic market can easily absorb 10, he said.

Last year, 24 percent of the crop was exported — the second lowest share in decades. And an increasing share of the exports stays in North America, what Fryhover likes to call Washington’s home court. “We’re going to ship the smallest amount that we have in the last 20 years,” he said. “That just shows you how fast things are changing.”

Port challenges

The Northwest Seaport Alliance, the marine cargo operations manager for the ports of Seattle and Tacoma, knows the challenges stymieing apple and pear shippers in recent years and is trying to address them, said Steve Balaski, business development director for the alliance.

But some problems — high freight rates and lack of efficient service to key markets — are global in nature.

Recognizing the challenges from congestion in 2021, last year the alliance partnered with the U.S. Department of Agriculture to pilot a project that would allow ag exporters to stage containers in advance at an “off-dock storage lot,” and the USDA would reimburse shippers for the cost. One such facility at Terminal 46 in Seattle now hosts the infrastructure to power stacks of refrigerated containers.

Balaski said they aimed to help ag exporters maintain consistency with their offshore customers, but he didn’t have specifics on which commodities had used the program. Good Fruit Grower reached out to the USDA for more specifics, but it did not share any data on the pilot program. The agency plans to continue it this year and is also examining the feasibility of raising the reimbursement rates of $400 per refrigerated container and $200 per regular container, which didn’t entirely cover shippers’ costs, Balaski said.

However, Good Fruit Grower interviews show fruit shippers haven’t even been using the program. Exporters say the backlog has abated; the storage solution would have been good to have in 2021, but it’s not worth the hassle now.

“You can’t get equipment far enough in advance,” Reinholt said, plus the fees were quite high for the limited amount of time that advanced storage might save. “You can pick up the container, load it in Wenatchee or Yakima, and take it back to the port in almost the same time, so you don’t save that much.”

One actual bright spot: new, direct service to Vietnam.

“Twenty-one-day service, you can’t beat that,” said Marc Pflugrath, international business development director at CMI Orchards, which still ships to Vietnam via other services, too.

The relatively high-end market still looks strong, he said. For example, he’s selling Ambrosia there for a nice return to the growers.

Fryhover also cited Vietnam as a strong market, one of the few offshore markets where the apple commission sees growth.

Pears

For pear exporters, the challenges at Seattle and Tacoma are even worse. Efficient service no longer exists from the Northwest to ports in South and Central American nations with strong pear markets.

“We’re basically shipping everything out of Oxnard or Long Beach,” in California, or trucking to Mexico, said Lina Sanchez, export sales manager for Duckwall Fruit of Hood River, Oregon. Those inefficiencies and higher costs dampen the once-bright potential for South American markets. “Brazil disappeared for us last year,” she said, because it now takes 60 days on the water instead of 30.

Luckily, U.S. pears have seen significant growth in the Mexican market — up 20 percent last year, Sanchez said.

“For Mexico, it’s very sunny. We are doing tremendous volumes at good pricing,” said Jeff Correa, director of international marketing for Pear Bureau Northwest, which promotes under the USA Pears label. “We’d normally have inflation concerns, but they continue to buy at higher pricing levels.”

The pear crop also came in on the light side this year, at 16 million boxes — a volume that can be moved close to home, Correa said. “The domestic market takes 12, Mexico will take three and Canada will take one.”

From that perspective, some shippers don’t see a reason “to take the risk of sending something 45 days on the water,” he said. But, just like the apple industry, he worries about ceding that space in export markets.

In markets farther afield, such as the Middle East and India, the industry has definitely seen its market share erode in recent years, Correa said. “It’s a big question mark as we return to normal-sized crops,” he said.

Sanchez noted the good news: The f.o.b. is high, driven by the short crop of apples and pears.

“That’s what we need to reset the minds of buyers, because things are not getting cheaper,” she said, “We have to find a new normal.”

“Normal-sized crops”

Beyond this short crop, the reduction in exports also reflects how much of the acreage that was fueling the export market has been removed.

But simultaneously, the industry needs to be building export markets for new varieties, such as Cosmic Crisp, Fryhover said.

The customers and the logistical capacity need to be there, because “even at 120 million boxes, we still need 10 million to go offshore,” he said.

Export desks are working hard to strike the balance between maintaining relationships with customers they want to keep — by supplying them — and maximizing the value of the short crop in the North American market.

Freight costs have certainly gone up domestically as well. “I can ship a container of apples to Vietnam for less than we can truck apples to the East Coast,” Pflugrath said.

And it doesn’t have to be a forgone conclusion that the export market won’t pay higher prices. It depends on the market and the customer, said Peebles of Chelan Fresh.

Inflation, after all, is global right now.

“You have to keep talking with customers. My team has been pleasantly surprised at the people who have said yes and the price they have said yes at,” Peebles said. “All of our jobs at the export desk are to maximize short- and long-term returns to the grower. The need to go export might have come down, but we still need to maximize it.”

One silver lining to the short crop is that it’s pushing up prices, and retailers can see that they can still move fruit at those prices.

“They don’t tend to fall back as low as they were when we get a full crop back,” said Reinholt.

He’s also optimistic that next year, freight costs and frequency will improve — barring another intentional slowdown as the longshoremen try to force contract negotiations, as they did in 2014.

“Next year, hopefully there will be lots of apples to go around and keep our customers happy and our growers profitable,” Pflugrath said. “No year is the same. Just when you think you’ve got the apple industry figured out, it will change.”

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment