The framework of these 12-year-old Packham trees (2,082 trees per hectare) on mini-Tatura is simple and very productive (55 to 61 tonnes per hectare annually, with 93 percent packout).

Our society is built on intricate hierarchical systems. Whether it is a private business, a government institution, the army, or a religion, we all fit into formally ranked groups. The same is often the case with wild animals and insects like ants and bees, which cannot survive unless they exist in organized groups. Look at a fruit tree in the same way.

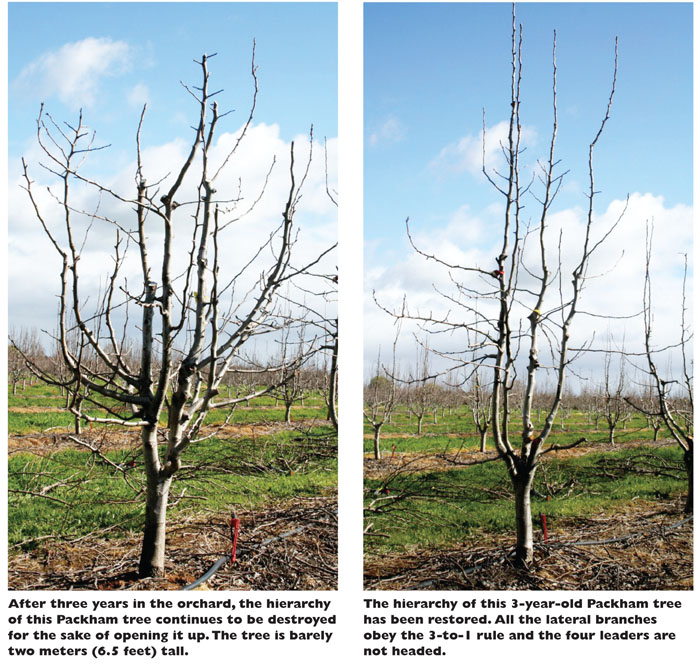

The framework, or structure, of a fruit tree consists of different parts of different ages. This framework is developed in sequential stages. First we establish the leaders as the primary framework. Then the lateral branches are formed as the secondary framework, followed by the fruiting units as the tertiary framework. These different structural parts form a hierarchy, which enables the tree to direct its energy into producing more fruit and less wood.

If you fail to establish a hierarchical framework in your young trees, you will have a fight on your hands, and probably end up with trees that produce mostly wood instead of mostly fruit. This is particularly so when trees are on vigorous rootstocks. The more vigorous the tree, the more important is the hierarchy of the tree’s framework.

A good example is the pear tree. Its growth habit is upright due to its strong apical dominance. As well, it is often not willing to form lateral branches. Many orchardists believe that heading the strong one-year-old upright shoots in winter will “open the tree up” and force lateral shoots to grow. Instead, only the top two or three buds under the cut form new upright shoots. Eventually, the tree wastes energy on producing big wood with many forks and limbs.

The solution is simple: Understand and respect the growth habit of the pear tree. Don’t fight it, you won’t win!

- Build a hierarchical framework, by first establishing one or more dominant leaders. Use stub cuts in summer to remove any lateral shoots. Depending on the quality and size of trees you planted, it may take one or two years for you to establish dominant leaders.

- In freestanding trees at a density of about 1,000 trees per hectare, establish four or five dominant leaders of equal size. Do not head these leaders.

- The next group in the hierarchy are the lateral branches. To create these, first apply a rest breaker, and then score the leaders in spring at “green tip.” Then remove the four or five buds immediately under the tip bud. The new shoot that develops from the tip bud provides the epinastic force to widen the angles of the new lateral shoots below it.

- In summer, remove any shoots that grow inside the leaders.

- Develop lateral shoots from the base up. Use stub cuts to remove shoots that develop higher up.

- Lateral branches must obey the 3-to-1 rule. This rule refers to the relationship between the diameter of the leader, and the diameter of the branches where they join the leader. Branches must have a diameter at their points of origin of one-third or less of the diameter of the leader.

- The last group in the hierarchy are the fruiting units, which develop on the lateral branches. Use the 1,2,3 rule of pruning to keep the fruiting units young and productive. This rule refers to one-, two- and three-year-old wood and is described in detail in Good Fruit Grower, January 15, 2010, on pages 34 and 35.

- When the trees have reached their maximum permissible height, head the leaders in late spring. This is called delayheading, and devitalizes growth in the heads. The later you make these heading cuts (but before the longest day), the weaker the regrowth will be. In extreme cases, double-delay head to subdue vigor in the heads. Delay heading maintains the tree’s hierarchical framework.

These principles and practices apply to all kinds of fruit trees and systems of training trees. In general, the simpler the tree structure, the easier it is to maintain a hierarchical framework.

Leave A Comment