In Eastern Washington, where temperatures are high and soils alkaline, blueberry growers may have a little more wiggle room about when to apply fertilizer to early season cultivars, compared to their colleagues on the west side of the Cascades. And while they’re at it, they also should consider using different rates and sources of fertilizers, target different nutrient ranges when they take leaf tissue samples and wait a little later on those samples.

The proliferation of blueberries, especially organic berries, in Eastern Washington prompted plant and soil scientists to update nutrient management advice to match the region’s climate and prevailing soil chemistry.

Washington is the nation’s largest blueberry producing state, with nearly half the state’s volume now grown on the arid east side where organic yields match or surpass those of conventional bushes to the west, according to the Washington Blueberry Commission. About 60 percent of Eastern Washington blueberries are organic, and that will probably go to 75 percent organic in five years, said Alan Schreiber, executive director of the commission. Western Washington is more than 95 percent conventional.

In spite of the growth, the crop is still relatively young in the dry climate, said Leif Olsen, a partner in Olsen Bros. Ranches near Prosser. He is a member of the blueberry commission, which has funded some of the nutritional research. His family’s company began planting some of the early trial blocks of organic blueberries in 2004.

“The soils here are so different,” Olsen said.

The learning curve has been steep and expensive, he said. Most published advice applies to soils on the western side of the Cascades, which is higher in moisture and organic matter. Growers from his area are still learning.

“What levels of nutrition do you have to put out to feed these things?” Olsen said.

Washington State University researchers have come up with some answers and are searching for more.

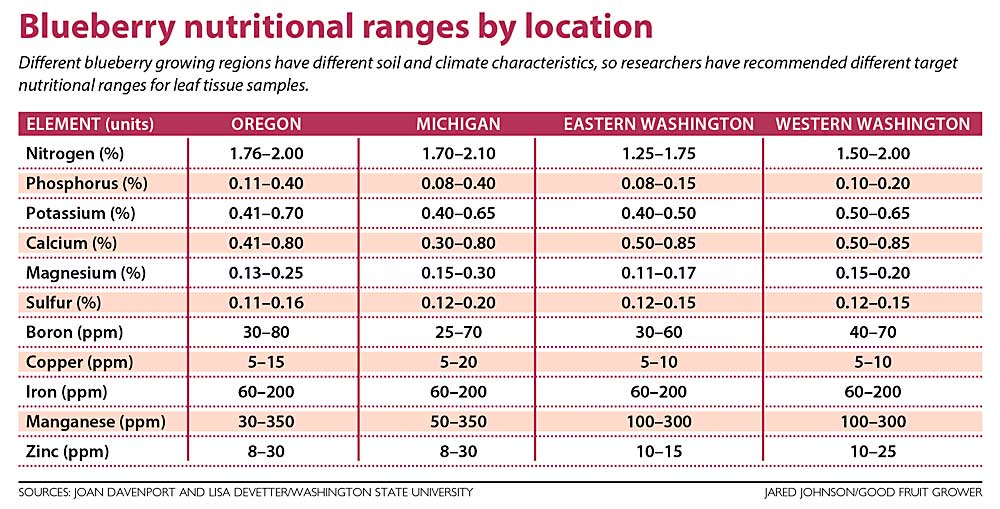

In recent years, Joan Davenport, a WSU professor emeritus of soil science, and Lisa DeVetter, a professor of small fruits horticulture, have determined and published target nutrient ranges for leaf tissue samples for both sides of the state (see chart). For example, Eastern Washington growers should shoot for between 1.25 percent and 1.75 percent nitrogen, while growers in Western Washington should aim for 1.50–2.00 percent. Also, nutrients stabilize in leaf tissue later in the summer in Eastern Washington, so researchers recommend a mid-August to late-August sampling time, later than that of northwest Washington and Oregon’s Willamette Valley.

In Oregon, the advice has always been to fertilize before harvest, but in a three-year project that ended in 2020, DeVetter and her team determined that in Eastern Washington, continuing fertilizer programs after harvest does no harm to early season cultivars such as Duke, one of the main drivers of the region’s blueberry growth. In trials near Prosser, they measured vegetative growth, bud development, winter injury, fruit quality and yields after a variety of fertilizer timings.

This means growers in Eastern Washington have some wiggle room, DeVetter said. They don’t have to stress about getting all their applications in before harvest, and delaying may even help a little. Generally speaking: Slower, more consistent fertilizer applications are better for plant uptake.

“It’s OK. You can be flexible with your early season cultivars,” she said.

However, she cautioned against applying the same advice to late-season varieties, for which late fertilizers could leave tender new growth susceptible to October frosts.

In addition, DeVetter is leading a six-year project funded by the Northwest Center for Small Fruits Research that examines differences in sources and rates of nitrogen fertilizers on Dukes. The team is trying a liquid fertilizer made from food scraps, blood meal, fish emulsion and a combination of other sources.

So far, Duke does not seem sensitive to the variable sources of nitrogen, but the study is only half over. Up until now, the researchers have been intentionally leveling potassium and phosphorus to control for the rates of nitrogen. They will stop doing that this year, to gain a broader understanding of the commercial product’s effectiveness, DeVetter said.

Blueberries need potassium, naturally found in many organic fertilizers, but the nutrient is building up in plant tissues at the fertilizer rates applied in the study. That can cause more harm than good. High levels of potassium in the plant are correlated with reduced yield. The next part of the study will include exploring whether growers can correct for this by stopping or cutting down on potassium applications, DeVetter said.

Determining optimal rates, timing and sources will help Eastern Washington growers cut down on costs, Olsen said. Almost all growers in the area use weed mats that make applications expensive and time consuming.

But the right cocktail for the region is out there, Olsen said. Blueberries grow just about anywhere. He recently visited Peru, one of the new leaders in the global blueberry trade.

“I saw them planted on what looks like beach sand,” he said. •

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment