Research in a newly planted organic vineyard showed just how difficult and labor-intensive weed control is under organic conditions. Not only can weeds and cover crops compete with young vines and reduce growth, but also mechanical means to control weeds can injure the tender trunks.

Dr. Carol Miles, extension specialist at Washington State University, recently completed a two-year trial of sustainable weed management in a three-acre certified organic vineyard in WSU’s Northwestern Washington Research and Extension Center at Mount Vernon. Results of the trial were published in 2012 in HortTechnology, the scientific journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science.

Miles says the results underscored the difficulty and importance of weed management in establishment of new vineyards. The trial compared five cover crop treatments and cultivation regimes for two years in a newly planted organic vineyard. The plot, planted in 2009, featured two early ripening varieties, Madeleine Angevine and Pinot Noir Precocé.

Cover crops offer many soil benefits and are often used in organic and conventional vineyards to help suppress weeds.

Although acreage on the west side of Washington State is miniscule—around 200 acres in the Puget Sound appellation, compared with the state’s total wine grape acreage of around 45,000—there is great interest there in organic viticulture. Westside growers would prefer not to use any chemical sprays, Miles said. Weed management without herbicides is challenging, so she embarked on research to learn more about suitable cover crops and mechanical means to control weeds.

“The trial showed how challenging weed control is in an organic vineyard and how critical in-row weed management is, early on, in a new planting,” Miles said in an interview with Good Fruit Grower.

“The west side has a 12-month, nonstop weed growing season,” she explained. “It takes greater effort here to control weeds than other locations because of the conducive weed-growing conditions.”

The trial included the following vineyard treatments:

- Cultivation in alleyways with hand weeding in the vine row (the control treatment)

- Grass cover crop (perennial ryegrass and red fescue) seeded in the alleyway with in-row tillage done with a specialty offset cultivator called the Wonder Weeder

- Winter wheat cover crop in the alleyway with in-row cultivation done by a handheld string weeder

- Austrian winter pea cover crop with in-row string weeder

- Austrian winter pea and winter wheat cover crop mix with in-row string weeding

Process and results

All of the cover crops were mowed at regular intervals when vegetation was about a foot tall. Vines were drip irrigated from June to September. For the control treatment, in-row hand weeding and alleyway cultivation were done twice in the first year and three times in the second. In the cover crop treatments, string weeding was done oncein the first year and four times in the second. Offset cultivation treatments were done once each year.

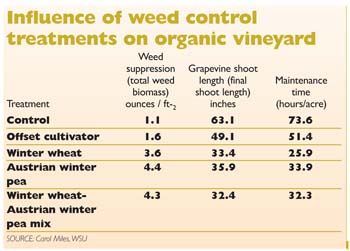

Researchers measured weed and cover crop dry biomass, vine pruning weights of the different treatments, and shoot growth of the vines. Labor required was also tracked for the treatments.

Researchers measured weed and cover crop dry biomass, vine pruning weights of the different treatments, and shoot growth of the vines. Labor required was also tracked for the treatments.

Cover crop and weed dry biomass differed significantly by treatment but not by grape cultivar. In 2009, droughty conditions prevented establishment of the grass cover crop mix, resulting in no cover crop in the offset cultivation treatment. Austrian winter pea and the winter wheat had the greatest biomass in the first year.

In the second year of the study, although both winter wheat and Austrian winter pea were seeded in the research plots in March, there was no significant biomass of the two crops in the treatments in July. Miles believes that maintenance problems coupled with poor cover crop establishment and competition from the two weed species of white clover and perennial ryegrass were to blame for eliminating the annual cover crops by mid-July.

White clover increased two to six fold between the July and September sampling dates. The trial illustrated the loss of the seeded annual cover crops throughout the growing season and the ability of white clover to become established in a mowed system. Annual ryegrass biomass was greatest in the Austrian winter pea alleyway and in the vine row on both sampling dates of the second year, reflecting the invasiveness of annual ryegrass when competition from a cover crop is minimal.

In both years and both varieties, shoot length and pruning weight were significantly greater in the control and offset cultivator treatments than in the cover crop/string weeding treatments.

In the white variety Madeleine Angevine, shoots in the control and offset cultivator treatments were twice as long at the September measurement as the other cover crop/string weeding treatments (50 inches versus 24 inches).

“This underscores the importance of reducing competition within the row of young vineyards,” Miles said. The shoot length difference was also significant in Pinot Noir Precocé, although not as dramatic.

While competition from cover crops can be a good thing in high-vigor vineyard sites, Miles said that during vineyard establishment, competition from weeds and cover crops should be kept at a minimum to encourage formation of the permanent vine structure.

She added that they had difficulty getting the offset cultivator to work properly without accidentally damaging the young vines. The handheld string weeder used to cut in-row weeds to the ground was also hazardous to the young vines and resulted in a 2 percent accidental grapevine death in the first year.

“Mechanical weed cultivation is doable in a young vineyard, but it takes more effort to make it work,” she said, adding that they put steel posts on both sides of the vines in an effort to protect them from the string weeder and offset cultivator.

Weed suppression was most effective and shoots the longest in the control treatment (cultivation in the alleyways and hand weeding in the vine rows), but it also required the most labor and maintenance time. Inversely, the three cover crop treatments required the least amount of maintenance and labor, but had the shortest vine shoots and greatest weed biomass.

“In a newly established organic vineyard, the most effective weed suppression technique allowing for maximum vine shoot growth would be clean cultivation, based on results in this study,” said Miles. “However, labor efficiency must be taken into consideration. Including a vegetation-free zone using a specialty cultivator can minimize the time needed for in-row hand weeding, while still allowing for good vine shoot growth.”

Another option would be to use conventional viticulture methods that use synthetic herbicides to control weeds during vine establishment. Once the vines are established, the grower would transition the vineyard to achieve organic certification, a step that requires three years.

Growers interested in organic viticulture should realize that weed control during plant establishment is critical and takes effort, she said.

“You can’t get behind in weed management.”

The two-year trial ended in 2011. The organic vineyard was damaged during the Thanksgiving freeze of 2010 and has since been removed. WSU no longer supports viticulture research at the research center in Mount Vernon. Miles now focuses on cider and vegetable research.

Leave A Comment