Organic pears can sell for about $10 more per box, but for growers interested in transitioning Bartletts and Anjous to organic, there’s a lot more to consider than just the potential for higher returns.

A panel of growers shared their perspective on shifting to organic pear production during the Washington Tree Fruit Association’s annual meeting in December: citing pest and disease pressure, nutrient management and marketing opportunities.

“Our organic customers only want certain sizes and grades,” said Jason Matson of Matson Fruit Co., located in Selah, Washington. “Otherwise it’s sold as conventional and then what’s the benefit? You’ll be sinking expensive organic dollars and getting a conventional return.”

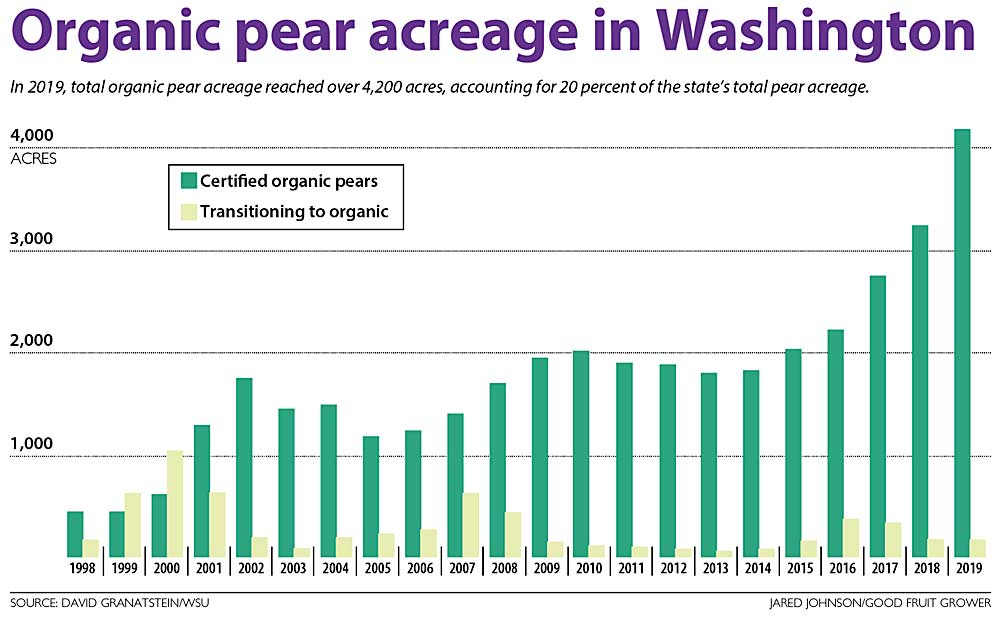

While almost 20 percent of Washington’s pear orchards were certified as organic by 2019, just 14 percent of the product was sold as organic that year, according to Washington State University emeritus professor David Granatstein, who tracks organic trends. There’s only so much demand for organic pears.

Don Gibson, president of Mount Adams Fruit, agreed that growers should consult their marketers before transitioning to organic. “If you are growing something like a third-grade Anjou, it has no home in the organic world,” he said. “You need to have the fruit your marketing department wants.”

As a vertically integrated fruit company, Mount Adams needs organic pears in its portfolio, even though organic orchards don’t always generate larger returns. The organic price premium fluctuates, Gibson said, and packouts can be a little lower than conventional blocks due to russet that stems from fire blight control, but retail customers want some organic in the mix.

For individual growers, however, the calculations look a little different, said Ray Schmitten, a pear grower from Dryden, Washington, and a horticulturist for Blue Star Growers who described ups and downs of profitability in the decades he worked as an organic consultant.

“There’s a margin of benefit, but every organic block I’ve been involved with, we’ve got to the point of diminishing returns,” he said. In his region, it’s hard to manage nitrogen to keep fruit size up for the long term without applying conventional fertilizer.

“If my fruit size is declining, I’d better get out” of organic certification, Schmitten said. “We love the ideology of it but can’t afford to lose the farm for the ideology.”

Before getting into organic, Matson said growers should consider whether their primary pest challenges could be managed organically and reckon with their record-keeping abilities. “Organic audits are thorough,” he said.

All three panelists recommended transitioning established blocks, even if the block was planted specifically for organic production. Gibson said that using conventional tools such as Apogee (prohexadione calcium) in the establishment years can help the pears get into higher-volume production faster, and then they transition.

Schmitten recommended setting up orchards with the option to do overhead wash systems, which reduce the fruit damage from psylla. That helps growers to transition to an organic or IPM psylla control program that largely relies on natural enemies. He said that even when he transitions a block back to conventional to boost fruit size with conventional fertilizer and resume weed spraying, he’ll pretty much stick to the organic pest program to protect the natural enemies.

“Pest control is the easy part. Once we build up the predators, we spend the same” as conventional, Schmitten said.

Nitrogen and vigor management pose the top organic challenge in North Central Washington, he said, while Gibson said in the Mid-Columbia, fire blight management is the top threat to organic blocks.

Rodent control can be an issue everywhere, panelists said.

“After leaf drop, we’ll go through with the brush rake and rake all the garbage from the weed strip into the center of the rows so it’s not right next to the trunks,” Matson said. That relocates the prime rodent habitat away from the trees, at least.

As of 2019, Washington had 4,200 acres of pears certified organic, according to Granatstein’s data. That’s up from just over 2,000 in 2015. Bartletts account for 38 percent of the acreage, with Anjous at 33 percent and Bosc at 15 percent.

Is that the top of the market? Perhaps.

“The market is inelastic,” Schmitten said. “When we first really got into organics in the mid-’90s, one orchard came in and saturated the market.”

The growers he works with through Blue Star want to stick with organic for Bartletts where they can, but less so with Bosc and Anjou.

While the panel billed itself as a discussion on what growers should consider if they want to get into organics, it’s just as important to know when to get out, Schmitten and Matson stressed.

“When disease or pest pressure is so bad you have to break out the conventional hammer to get control back before you lose it,” Matson said. “And when the market is just too small. Pears are a niche item in themselves. Organic pears are a niche of a niche. Organic Seckel or Red Anjous are a niche of a niche of a niche. Retailers don’t want these too nichey varieties.” •

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment