During the 2019 U.S. Apple Crop Outlook and Marketing Conference in Chicago, Randy Riley, the Kroger Co. director of produce merchandising, reported that consumer engagement and consumption of apples has dipped in the past five years, with Kroger’s shopper card data showing a 4 percent reduction annually.

Since Kroger is one of the nation’s largest retailers, this could represent an alarming decline in demand for fresh apples.

Riley’s statement raises two questions: One, is the Kroger experience of declining apple sales typical across U.S. food retailing, and two, if so, what does the U.S. and Washington apple industry need to do about it?

Evidence from USDA data

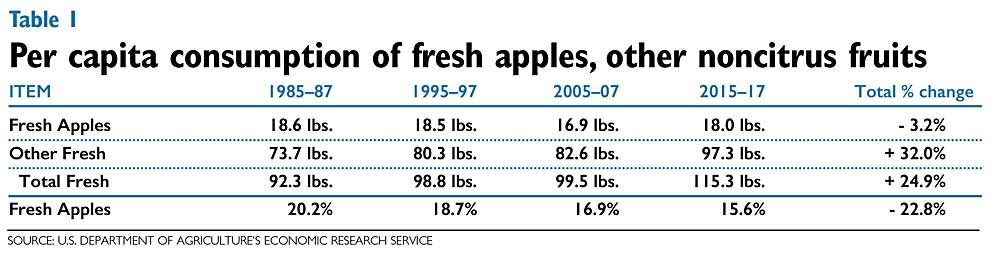

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service publishes annual estimates of per capita consumption of fresh fruits. The latest data are for 2017. (See Table 1)

While per capita consumption of fresh apples has remained around 18 pounds for much of the period from 1985 to 2017, consumption of other noncitrus fruits has soared by 32 percent. The fresh apple share of the market has fallen by almost 23 percent.

If fresh apple consumption had kept pace with that of all fresh noncitrus fruit, about 37 million more boxes of fresh apples would have been sold from 2015 to 2017.

Evidence from “Fresh Facts on Retail”

United Fresh has been publishing its “Fresh Facts on Retail,” a quarterly review of retail sales of fresh produce, since late 2007. On an annual basis, the volume of fresh apples sold per store rose by 24 percent between 2008 and 2014, but fell by 5.2 percent between 2014 and 2017.

In contrast, the volume of all fruits rose by 25.4 percent between 2008 and 2014 and by a further 7.8 percent between 2014 and 2017. The fresh apple share of fresh fruit slipped by 12 percent between 2008 and 2017, a similar trend to that shown in the USDA data.

Unfortunately, the methodology used in Fresh Facts on Retail was changed after 2017, so it is not possible to compare results for 2018 with those of the previous decade.

In 2018, Fresh Facts began reporting total retail sales and not sales per retail outlet, so only two years of the newer data are available. While the method changed, the message did not. Between 2017 and 2018, the volume of fresh fruit sold fell by 0.2 percent, but the value rose by 0.7 percent due to slightly higher prices.

In contrast, the volume of fresh apple sales fell by 3.8 percent, and the value by 3.6 percent, similar declines to those reported by Kroger’s Riley.

Evidence from Belrose fresh apple index

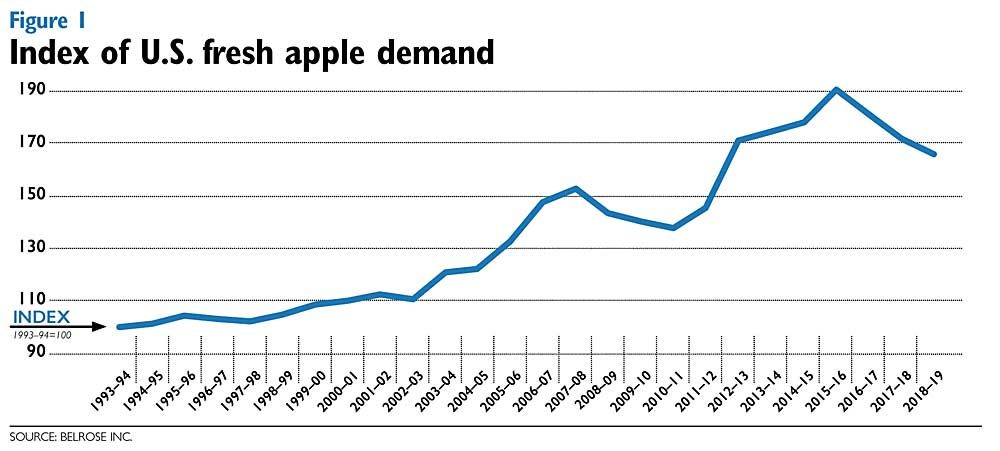

Belrose Inc. has been calculating an index of U.S. fresh apple demand since the 1993–94 season. The index is more comprehensive than either USDA or United Fresh data in that it accounts for the volume of shipments, the index of fresh apple prices and a correction for inflation.

Figure 1 shows that real U.S. apple demand grew little between 1993–94 and 2002–03. It grew rapidly between 2002–03 and 2007–08 before falling the next three seasons due to the impact of the Great Recession. It entered another period of fast growth between 2011–12 and 2015–16. However, it has declined by 5 percent in both 2016–17 and 2017–18, and by a further 3.2 percent in 2018–19. So, the Belrose index confirms the decline in fresh apple demand noted by Riley.

How should the industry respond?

Washington consistently accounts for over 70 percent of fresh apple supplies to the U.S. domestic market, so clearly it has a major stake in responding to falling U.S. demand. If that trend continues, the Washington apple industry’s multibillion-dollar investment in modern growing, packing and marketing facilities is at increasing risk.

Speculating about why demand has fallen, Kroger’s Riley argues that too many apple varieties with similar flavor profiles may confuse both the retailer and the consumer. There is also too much supply of “less-than-optimal eating apples,” in his words. “The increased variety tactic is clearly not lifting the category and it’s not translating to the consumer.” He also pointed out that “external competition from other fresh produce items may be another reason consumer apple engagement has dipped.” That last argument is supported by USDA and United Fresh data.

Promotion is part of the answer.

There are currently 27 state apple associations that promote fresh apples in the U.S. market, including leading states like New York, Michigan, Pennsylvania and California. However, Washington state, the source of over 70 percent of fresh apple sales in the U.S., has no coordinated promotional program in the domestic market.

The Washington Apple Commission’s domestic promotional program was terminated in 2004 after being declared unconstitutional. Meanwhile, promotional programs for many competing fruits and vegetables continue unabated. Ironically, among these are Washington pears and sweet cherries.

Major Washington apple marketers have their own individual promotional programs, but their resources are limited relative to the vast U.S. market. Many tend to concentrate promotion on their own proprietary varieties. Most other apple varieties grown in Washington fall into what I have called the “orphan” category — they no longer have a strong promoter in the marketplace. Yet those orphan categories still account for over 80 percent of Washington apple volume.

Two steps to a cure

For the Washington apple industry to correct declining demand, it will need to take two major steps:

Industry leaders will have to accept the fact that competitive conditions have changed significantly since the Washington Apple Commission’s domestic promotion program was terminated in 2004. The favorable trends that helped fresh apple sales between 2003 and 2008 and between 2011 and 2016 have evaporated. The retail landscape has changed dramatically, and consumer needs have become much more complex. Only a coordinated, scientifically targeted effort by the Washington apple industry can reverse the decline in U.S. fresh apple demand.

A way will have to be found to restore the state’s domestic apple promotional program that will not be declared unconstitutional. Feasible alternatives include placing the program within the Washington State Department of Agriculture or creating a voluntary program in the format proposed by Cornell University’s Kent D. Messer, Todd M. Schmit and Harry M. Kaiser in an article in the American Journal of Agricultural Economics in November 2005. What is needed is the will to find a formula that will win broad industry support.

The Washington apple industry can continue to face declining demand, or it can take decisive action to restore a well-funded promotional program aimed at halting or even reversing the decline. The second option seems desirable if the Washington apple industry wants to protect the huge investment that it continues to make in apple growing, packing and marketing. •

—by Desmond O’Rourke

Desmond O’Rourke is president of Belrose Inc. of Pullman, Washington, publisher of the monthly World Apple Report.

Leave A Comment