In a Washington State University laboratory in Pullman, staff and students smelled a lot of pears this fall.

But these trained evaluators smelled the right way, using two or three sharp and noisy inhalations to propel volatiles into sensitive nasal nether regions. No debonaire wafting, as when screening a wine at dinner.

“Aggressive sniffing, that’s what we teach,” said food science professor Carolyn Ross.

To determine which pears to plant, Northwest growers need to know what consumers want in a pear. So, the industry commissioned food scientists at WSU and Oregon State University to run evaluations, aiming to put some empirical data behind subjective traits of aroma, taste and texture.

The Northwest pear industry, beset with low prices, is seeking to diversify its variety portfolio. One idea is to start a breeding program at Washington State University. WSU already has a pear rootstock breeding program, searching for dwarfing options, and an apple breeding program best known for the WA 38, marketed as Cosmic Crisp.

But building a breeding program is an expensive and lengthy endeavor. A shorter-term idea: Run trials on existing selections not widely planted in Washington and Oregon.

Either way, the industry needs data on consumer preferences. That’s where the food scientists came in.

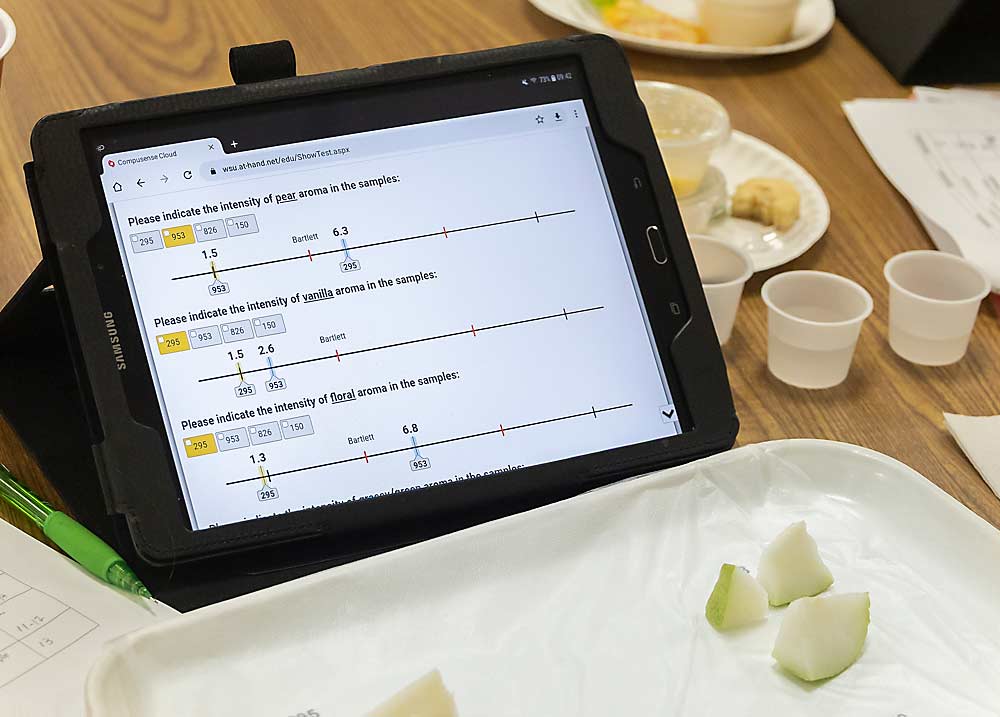

At WSU, Ross trained a panel of 10 student and staff evaluators how to recognize specific pear attributes, broken into categories of aroma, texture, taste, mouth feel and appearance. Taste attributes consisted of sweetness, sourness and bitterness, for example. Aroma attributes included floral, grassy and fermented.

Recognizing those details took practice. Ross trained her panelists for 15–20 hours, like bloodhounds. To help them recognize and measure the aroma of, say, vanilla in a pear, she gave them a waft of vanilla extract. Only then, did they rate the pear varieties on a scale of 1–15 for each attribute.

The evaluators at WSU did not indicate preference. “Trained panelists, we don’t ask what they like,” Ross said.

The preference question came into play in late October at OSU’s Food Innovation Center in Portland, where 120 pear shoppers from a cross-section of demographics blindly sampled six to eight varieties, including both industry staples and uncommon cultivars, ranking them largely on their subjective preferences.

“It’s all about liking,” said Ann Colonna, sensory program manager at OSU and Ross’ co-researcher on the project.

Each participant was paid $40 for the hourlong testing, which involved 20–30 computer questions about characteristics for each sampled pear. They also were asked how willing they would be to pay for the sampled pear.

Colonna plans to repeat the sampling in January with winter pear varieties.

In the end, data from Ross and Colonna about characteristics and preferences will inform growers and researchers about what to plant, said Tory Schmidt, a project manager for the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission, which manages scientific grants for the fresh and processed pear committees charged with collectively marketing Washington and Oregon pears under federal marketing orders.

Ross and Colonna will present their results in February at a research review.

The information could yield some selection goals for field trials of existing outside varieties or a new breeding program, Schmidt said. However, even if neither of those things happens, consumer preference data will help growers and packers fine-tune their horticultural, storage and sales practices.

Through surveys in the past, consumers have told the industry they might buy more pears if they didn’t have to wait as long for them to ripen, but they based those opinions on traditional European pears expected to ripen into a soft, buttery texture. Not all pears are like that, said Schmidt, also a commercial pear grower.

The evaluations aim to broaden the palates of consumers with tastes, textures and smells they didn’t know a pear could deliver.

“Maybe they don’t know what they would like because they’ve never been exposed to something (different),” Schmidt said.

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment