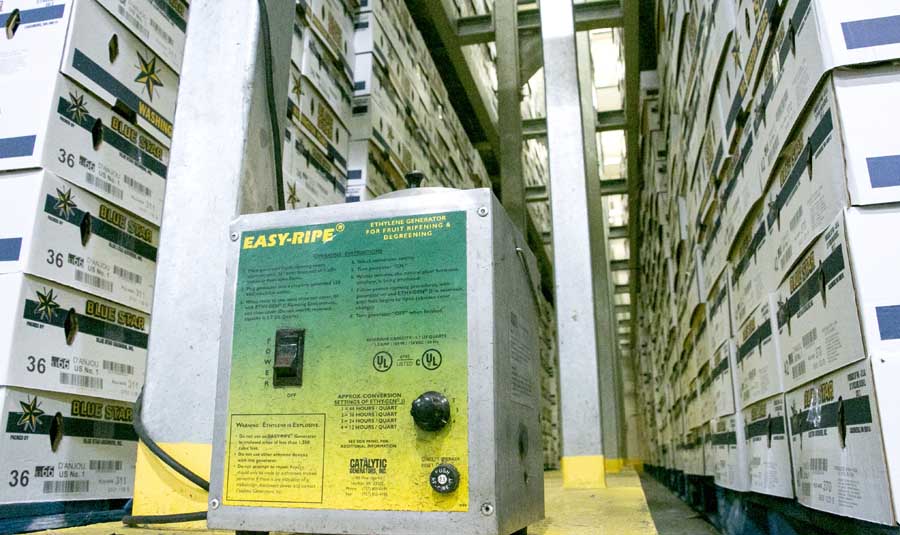

Ethylene treated pears are shown inside a controlled atmosphere room at Blue Star Growers in Cashmere, Washington. Though the process is nothing new, industry officials still urge both shippers and retailers to condition pears so they are riper when a shopper picks one up. The device in the foreground emits the ethylene gas that permeates the vented boxes. (Ross Courtney/Good Fruit Grower)

Conditioning pears is nothing new, but industry officials are still asking shippers and retailers to do more of it.

“It’s been an ongoing process,” said Kevin Moffitt, president and CEO of Pear Bureau Northwest, which promotes fresh pears from Washington and Oregon under a federal marketing order and the brand USA Pears.

For 15 years or so, the Pear Bureau has encouraged both retailers and packing houses to build controlled atmosphere rooms in which to condition pears, kick-starting their natural ripening process with ethylene gas treatments.

The theory is that shoppers will buy more pears if the fruit is closer to ripeness at the time of purchase.

And it’s true: In 2012, conditioned pears sold nearly 20 percent better than unconditioned pears in a study by the Pear Bureau and Nielsen Perishables.

“If people understand you have ripe pears or ripe fruit, you’re going to distinguish yourself from your competition,” Moffitt said.

Chalk it up to the obvious. Impatient shoppers don’t want to either wait for their fruit to ripen or help it by, say, placing it in a bowl next to a banana. (Bananas release a lot of ethylene that will hasten ripening of any other nearby fruit.)

The pear on the left — note the blush hue — has been ethylene treated. The pear on the right is untreated. (Ross Courtney/Good Fruit Grower)

A total of 71 percent of pear shoppers eat their fruit within three days of purchase, according to Pear Bureau statistics.

“Today’s consumer doesn’t want to work that hard,” said Kathy Means, vice president of industry relations for the Produce Marketing Association based in Newark, Delaware.

Asking shoppers to wait two weeks after purchase before eating? “It’s the stupidest thing you’ve ever seen in your life,” said Roger Pepperl, vice president of marketing for Stemilt Growers in Wenatchee, Washington, which conditions some of its pears.

Conditioning is getting more prevalent. Nationwide, 47 retailers offer treated pears, up from 35 five years ago.

But only about 35 percent to 40 of green d’Anjou pears receive ethylene treatments before they reach store shelves and even less of other varieties — 15 to 20 percent of Bartletts and only 5 percent of Bosc, said Moffitt, who hopes the food service industry adds red d’Anjous to the list next.

D’Anjous, both red and green, are the easiest variety to treat. After an ethylene treatment, their ripening slows again in cold storage.

Bartletts, on the other hand, continue to ripen after conditioning and need to be sold within two weeks or so, but they are extremely firm right after harvest, so most Bartlett conditioning happens early in the season. Other varieties simply ripen better on their own or don’t respond as well to ethylene.

The Pear Bureau publishes a manual for conditioning of different varieties and contracts with a consultant to help both shippers and retailers start a condition program or fine-tune one already in place.

Part of the reluctance is deciding whether the retailer or the shipper bears the responsibility for conditioning.

Many shippers would rather retailers handle it, preferring folks further down the line risk damaging ripe fruit by shipping it to their stores.

Meanwhile, ethylene chambers with generators, vented boxes and forced air temperature control require a sizeable capital investment and space.

Of the 54 Northwest pear shippers, 32 have conditioning capability, according to Pear Bureau Northwest’s roster.

“You also need to have a significant enough volume to justify the expenditure,” said Dan Kenoyer, general manager for Blue Star Growers in Cashmere, Washington.

However, the service adds value. Blue Star custom conditions for many of its buyers and charges a premium for conditioned fruit, Kenoyer said.

In the past, many packing companies like Blue Star relied on roaming ethylene trailers. The company built four conditioning rooms in 2005.

The chambers, each with a bright yellow door and resembling a fire station bay, each can hold two tractor-trailer loads full of pears.

Inside each chamber is an ethylene generator the size of an office printer and probes that track the internal temperature of the fruit.

To condition pears, shippers warm the fruit to roughly 65 degrees, gas for roughly 24 hours and then cool to 32 degrees or so. The process takes three to four days.

However, the fruit still is not ready to eat. It has another three or four days to ripen, allowing time for shipment.

The ethylene treatment “is like we kick-start the process to a certain point,” said Josh Dailey, assistant shipping manager for Blue Star.

Retailers routinely condition bananas in ethylene chambers in their distribution centers, but not as often for pears, avocados, mangoes and tomatoes.

They often don’t have the space and prefer to use their limited capacity for bananas. Some also fear it will increase their shrink due to pears going bad before purchase.

Only five — Raley’s, Thrifty Foods, United Supermarkets, Wal-Mart and Wegmans — treat pears in their own facilities, according to a roster from the Northwest Pear Bureau.

Wal-Mart was one of the first, said Gary Campisi, senior director of quality control for Wal-Mart’s fresh grocery division.

The retail giant started conditioning bananas in 1993 as soon as it began building its own distributions centers. The company started with pears around 2000 to prep the fruit for in-store samples and customers loved it.

“It doesn’t take a whole lot of leap of logic to figure that one out,” he said.

Today, Wal-Mart conditions Bartletts and d’Anjous in all 44 of its distribution centers, using the same 600 ethylene rooms as bananas, Campisi said.

They do not condition Bosc pears because they don’t sell as many, and customers have a wider variety of preference for the ripeness level of Bosc pears than d’Anjous and Bartletts.

Wal-Mart also buys pears conditioned by the shipper but will run them through the chambers again if the pressure of the fruit is above 12 psi.

“My personal opinion is the retailer who is closer to the customer” bears the responsibility for conditioning, Campisi said, arguing he would rather control the quality of his customer’s eating experience than someone else.

“If you’re focused on sales, on top line sales, then you are going to want to have a good ripening program,” he said. “Not just the one-time sale but the repeat sale.” •

– by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment