Anyone associated with Michigan pears will tell you that, small though the state’s industry might be, it wouldn’t exist without Gerber. The iconic baby food maker began purchasing pears from Michigan growers not long after it was founded in 1927, and it has been purchasing the majority of the state’s crop for decades.

That pattern didn’t change after food giant Nestle acquired Gerber in 2007, and today Gerber/Nestle wants to be the future of Michigan pears, too — or at least fund the research that puts that future on a solid footing.

“Michigan pears have been a good fit for us for a long time,” said Drew Afton, an agronomist with Gerber/Nestle. “We don’t see a reason to change.”

The baby food company gets most of its pears from California — New York is another supplier, and Washington state supplies organic pears. Sourcing from multiple regions is critical to keeping a consistent supply, but as the only large pear processor left in the Eastern United States, Gerber/Nestle wants to ensure a viable pear supply closer to Fremont, Michigan, where the company was founded and still has a processing plant, Afton said.

To maintain, and enlarge, that local supply, Gerber/Nestle is funding Michigan State University research on new varieties, rootstocks and management systems for Eastern growers.

“Our research is as much to ensure our own supply as to keep the pear industry going,” Afton said. “We might not get all those pears in the end — they might go to the fresh market — but that’s OK. We need the pear industry to be bigger and broader in order to preserve our own supply.”

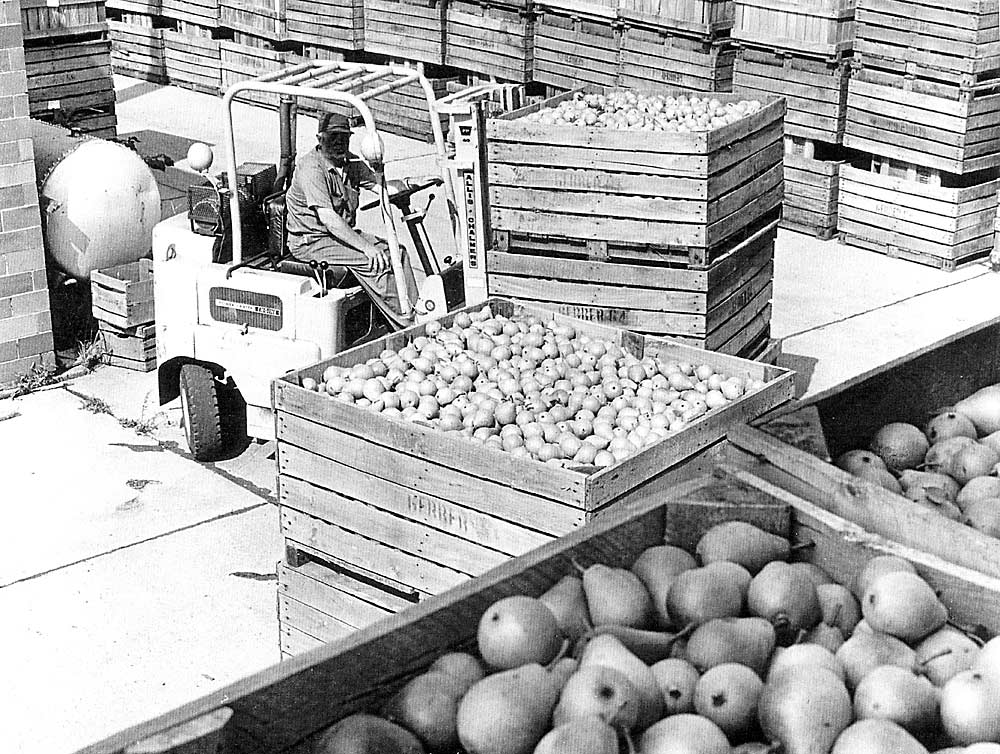

Though Michigan remains a diverse fruit state, its pear industry has stayed relatively small. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, 160 Michigan farms grew 650 acres of pears in 2018, most of them Bartletts grown on decades-old trees. A smattering of that fruit goes to the fresh market, but Gerber/Nestle processes most of it.

There are two main constraints on the growth of the Michigan pear industry.

“Between pear psylla and fire blight, Michigan is not an ideal place to grow pears,” said Todd Einhorn, an MSU horticulturist.

Old relationships

After a big wave of plantings in the 1960s and ’70s, Michigan pear growers slowed the effort. The trees struggled with fire blight, pear psylla and inconsistent yields. Under the circumstances, growers didn’t see the point of waiting nearly a decade for new trees to start producing, said Scott Lewis, who’s still tending 18 acres of pear trees his grandfather planted in 1966. Lewis sells a small percentage of fresh Bartletts out of his New Era, Michigan, farm market every year, but the vast majority still go to the nearby Gerber/Nestle plant.

Chris Falak, Gerber/Nestle’s category manager for fruit and vegetables, said the company buys an average of 800 tons of pears annually from 13 Michigan growers whose orchards stretch from the southwestern to the northwestern part of the state. Many of those farms have been supplying Gerber with pears for generations, with an average relationship of 38 years.

Lewis and another grower, Todd Fox, exemplify the long-term relationships Gerber/Nestle has with its growers and the company’s efforts to keep those relationships going.

With 120 acres near Shelby, Michigan, Fox is probably the largest pear grower east of the Mississippi River. On top of the 80 acres his grandfather planted in the 1960s, Fox added 10 acres in the ’90s, and planted 30 acres of high-density trees in the last couple of seasons, all meant for Gerber/Nestle.

In his 30 years of growing asparagus, cherries, peaches, apples and wine grapes, pears are the only commodity that hasn’t gone down in price. That’s due to Gerber’s consistent purchasing over the years, Fox said.

In spite of the challenges, Lewis’ and Fox’s old pear trees are still producing. Properly managed pear trees can yield fruit for decades.

“As long as Gerber keeps buying pears, these trees will outlast me,” said Fox, 50, standing in a block of trees that was planted in 1963. “Economics will push these trees out, not the grower.”

But even pear trees don’t last forever — and growers don’t either, said Lewis, 51. For the Michigan pear industry to have a future, modern varieties, size-controlling rootstocks and high-density plantings will be required, as in the apple industry.

“New growers need to get excited about planting pears,” Lewis said. “They need to know that if they put a pear block in the ground, it will be there in the future.”

New research

Gerber/Nestle hosted meetings with growers and researchers over the past few years, trying to figure out what it can do to preserve and expand Eastern pear orchards. To tackle the most frequently mentioned challenges — fire blight, pear psylla and inconsistent fruit set — the company started funding MSU research projects, Afton said.

MSU Professor John Wise studies the use of biopesticides on pears and alternative delivery methods such as trunk injection: delivering pesticides directly into the tree. Trunk injection offers several advantages over the typical spray method, such as preserving crop protection materials, protecting biopesticides from environmental degradation and doing no harm to beneficial insects. The method does pose economic and logistical difficulties for growers who have to cover hundreds of acres, however. It might be a good fit for organic pears, Wise said.

Gerber/Nestle also funds the research of MSU’s Einhorn, who studies high-density training systems for pears, new varieties such as Cold Snap and Gem, and dwarfing rootstocks. Cold Snap, the brand name for a Bartlett descendant developed in Ontario, Canada, and commercialized by the Vineland Research and Innovation Centre, shows resistance to fire blight. Gem, bred by the U.S. Department of Agriculture in West Virginia, promises precocity, fire blight tolerance and little russetting. It has had virus problems, Afton said, but work is being done to clean up the scion wood.

Fox recently planted Gem, Cold Snap and a few experimental varieties on OHxF rootstocks. The new trees are planted closer than his ancient pear blocks, about 8 feet apart, but Fox didn’t want to go any tighter than that. He’s worried about fire blight.

Lewis decided to give high-density pear trees a shot. He recently planted 1,000 trees of Cold Snap on OHxF 87 at 12- by 3-feet and 12- by 6-feet spacings. He expects the trees to start producing in three or four years. If Cold Snap shows consistent resistance to fire blight, it could be a “huge player” in Michigan, he said. •

—by Matt Milkovich

Leave A Comment