SOURCE: Washington-Oregon Canning Pear Association

Over the years, Jay Grandy has negotiated long and hard with Pacific Northwest pear processors over the prices that they would pay growers, but this year Del Monte Foods announced it would voluntarily pay almost $30 a ton more this season than it had committed to.

“This is definitely unprecedented,” said Grandy, who has managed the Washington-Oregon Canning Pear Association since 1998 and has been involved in the processed pear industry for 30 years. “Certainly, it hasn’t happened in that time period.”

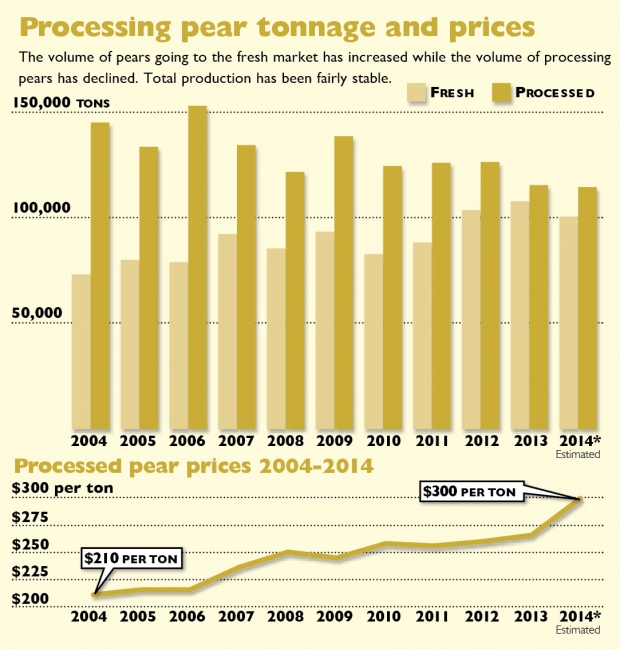

But Grandy wasn’t totally surprised when Del Monte announced the move last December. Growers had long complained that returns for growing processing pears barely covered costs. Between 1990 and 2010, the negotiated price for No. 1 grade pears hovered for the most part between $200 and $250 a ton. For the past few years, it’s been around $260 a ton, and for 2014 it would have been $272 a ton (see “Processing pear tonnage and prices”).

Jay Grandy

“The growers have spoken loud and clear over the years that they can’t get by on what Del Monte was paying,” Grandy said. “They’ve been looking at the attractiveness of apples and cherries and seeing that they would be better off to plant those varieties than put more Bartletts in the ground.

“It’s a matter of competitive returns from other opportunities,” he added. “A lot of growers have told them where they were at—$272 a ton—is just not enough to keep worrying about Bartletts.”

Another factor is that Del Monte bought the fruit-processing plant of Snokist Growers two years ago, which increased its capacity, Grandy said. “They’ve got to run tons to make it pay, so the real issue is getting growers to continue to deliver those Bartletts for processing. They’re worried that growers are going to pull out old Bartlett orchards and not replace them.”

Smaller crop

Also coming into play is a smaller total Bartlett crop and a trend for a higher percentage to go to the fresh market. Last season, the Northwest produced 233,000 tons of Bartletts, with 115,000 going to canners. This year’s crop was estimated at 225,000 tons or less.

Northwest canners sometimes haul pears from California for processing, but California also has a short crop this year (150,000 tons, down from 168,000 tons in 2013), and prices there are higher, too. (See “Pears shine bright in Golden Sate” on page 24.)

“They’re not going to bring them up here,” Grandy said. “There are too many good opportunities for the growers down there.”

The Canning Pear Association used to negotiate annually with the Northwest pear processers but switched to multiyear agreements. The last contract was signed in 2012 to cover the years 2012 ($260 a ton), 2013 ($266 a ton), and 2014 ($272 a ton).

Grandy said he had been discussing the situation with his board and was going to try to reopen the negotiations for the 2014 crop when Del Monte announced it would pay $300 a ton. “The incentive was there for Del Monte to have to do something to get tonnage, so I was sort of, but not totally, surprised.”

There are now three Northwest pear canners: Del Monte, based in Yakima; Northwest Packing Company, based in Vancouver, Washington; and Seneca Foods Corporation. Both Northwest and Seneca announced they would match Del Monte’s price.

The contract price for second-grade pears is 62 percent of the number-one grade price, so that will increase to $186 this year. Seneca and Northwest, which used to treat number-two grade pears as culls (with a return to the grower of $1 a ton), will pay the same as Del Monte for number-two grade.

But, with number twos typically making up 3 to 4 percent of the crop, that won’t have a major impact on grower returns, Grandy said. In 2015, the association will negotiate with the processors for the upcoming crops.

“Growers are in a more favorable position than they’ve been in a long time,” Grandy said. “I’m optimistic that we’re going to change the price upward, but I don’t have any idea how far it will go.”

These will be the first negotiations that Seneca Foods has been involved in, because the New York-based company didn’t have a processing plant in the Northwest when the last contract was negotiated in 2012.

Two years ago, Seneca bought the Sunnyside plant of Independent Foods, which never negotiated because it used a different payment method, similar to the one used for fresh fruit. Growers received what the fruit sold for, less charges for processing.

Grandy said The Food Institute is no longer publishing statistics on retail prices and volume, but it’s thought that sales prices for canned pears have increased. He had not yet seen the end-of-year (June 30) inventory reports from the processors, but he expected it would show one of the lowest inventory levels in a long time.

The volume packed last year was down from previous years and the product has been selling at a good clip. •

Leave A Comment