The modern orchardist’s most important tool isn’t pruning shears or a spray tank, a tractor or harvest platform: It’s an Excel spreadsheet.

Growers Sam Godwin and Rod Farrow both emphasized the game-changing impact the Microsoft software has had on their farms during “Know Your Numbers,” a presentation offered during the International Fruit Tree Association’s annual conference, held virtually in February.

Excel spreadsheets “changed the world” for Godwin, allowing him to look at his business in a more multifaceted way, he said. Godwin grows about 450 acres of apples, cherries and pears with his brother in Washington state’s Okanogan Valley. About 15 years ago, the brothers started transitioning to organic production, to differentiate themselves from larger, more vertically integrated producers.

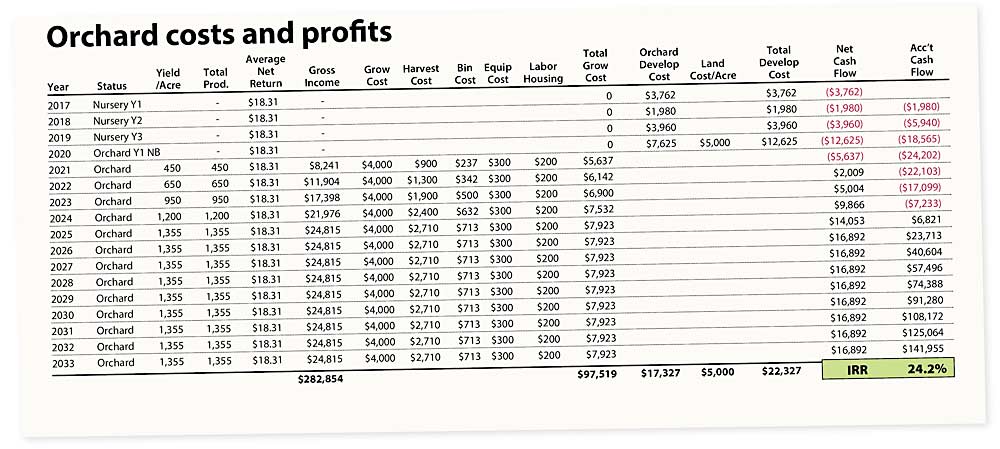

When Godwin started plugging his orchard’s cost and profit numbers into spreadsheets, it helped him clarify his biggest expenses, as well as the areas that had the most potential for revenue growth. Based on these numbers, he created a more data-driven business model — an approach that makes it easier to make tough decisions.

“It does the math for you,” Godwin said. “It’s not just, ‘Pick a number and hope.’ It’s, ‘I’m going to do X and here’s my expected outcome.’ I rarely second-guess a removal decision now, but I do second-guess deferring removal.”

When buying a piece of equipment, for example, Godwin’s main focus isn’t the cost but rather how much it can increase his cash flow by improving fruit quality or saving on labor.

Spreadsheets also helped Godwin home in on the varieties, sizes and grades that earn him the most money. With Honeycrisp, for example, he learned that going up one grade in quality can net him another $50 per bin. Loading an extra pack per bin can net him an extra $20. Using reflective fabric to boost apple color can add even more value.

“In the simplest terms, we want more target fruit per acre,” Godwin said. “If we can get more target fruit per acre, it will make us more money in the end than, say, a whole bunch of bins per acre.”

Farrow, former owner of Lamont Fruit Farm in Western New York, credits time spent on spreadsheets for the farm’s success as well.

“I could design spreadsheets that had meaning to me, and designing them took me down roads I wouldn’t have gone down if I was in the orchard,” he said. “I have calluses now from my keyboard, not from pruning.”

Farrow gave an example: looking for a new planting site. Typical sites in his region cost $4,000 per acre, but he found an ideal site that cost $8,000 per acre. The site had everything he was looking for — access to water and a frost-free slope, so purchasing a wind machine wouldn’t be necessary. But how could he justify the doubled cost?

When he crunched the numbers, he learned that buying the more expensive site would only lower the long-term profitability of the block planted there by a negligible amount. And he knew it had the potential for excellent yields, which would more than make up for the loss. That made the decision to purchase very simple.

“You drive business by increasing income, not by trying to save money,” he said. “You cannot save your way to prosperity.”

Farrow gave another example: It costs $600 to $700 to lay down and then remove reflective fabric in an acre of Minneiska (trade name SweeTango). Eighty-count SweeTangos are worth 35 cents each, but only if they’re at least 50 percent red (any lower than that and they have no value). The Minneiska block has 2,000 trees, so if the fabric reddened only one apple per tree above the 50 percent threshold, it would net an extra $700 for that block.

“Change one apple per tree and it’s paid for,” Farrow said. “Change two and you double your money. It’s simple math.”

From 2004 to 2019, Lamont Fruit Farm’s labor costs doubled and its chemical costs tripled. During the same period, however, the chemical cost’s share of each dollar of income stayed consistent at 11 cents, while the labor cost’s share actually shrank from 52 cents to 41 cents per dollar of income. They’re absorbing those increasing costs because they’re making more money, he said.

Spreadsheets can do wonders for your business, but their output is only as good as their input. The numbers entered need to be as accurate as possible. Farrow and Godwin said there are two main ways growers can get accurate numbers: precision crop load management and good relationships with packers and marketers.

“If you don’t measure it, you can’t manage it,” Farrow said. “If you want to influence the outcome, you have to know what the heck is going on.”

Godwin said packers and marketers have lots of useful data and will share it with trusted partners.

“Their sole purpose is to get the right fruit in the right box, on time, to the right customer every day,” he said. “You have to know what the right fruit looks like — and turn that into action on your farm.” •

—by Matt Milkovich

Leave A Comment