Even just a year ago, farmers stood in the back of the room for discussions about mental health, said Julie Jesmer, farm stress and suicide prevention coordinator for Washington State University Skagit County Extension.

That’s already changing, she said. The topic of mental health is gaining traction and acceptance in agricultural circles. It shows up on conference agendas, surveys are underway, and farmers are more willing to discuss things like stress, depression and suicide.

“They’re coming up to me,” Jesmer said.

To capitalize on the momentum and shed light on the problem, Jesmer and fellow leaders of a Western U.S. farmer mental health program have tabulated results from a baseline survey of farm operators and owners. Colleagues are making similar efforts to survey farm laborers, too.

Farmers take their own lives at a higher rate than the general U.S. population, driven in part by remote lifestyles, heavy debt, family legacy pressure and an ethos of self-reliance. The very mission of farming — feeding the world — carries a lot of emotional weight, Jesmer said. It’s been dubbed “the agrarian imperative.”

“The idea of losing the land is so traumatic … that they will do just about anything, healthy or unhealthy, to maintain possession of that land,” Jesmer said.

Meanwhile, farmers present a unique challenge to mental health professionals because they control few external stressors — such as weather and prices. Meanwhile, each year, the job becomes more complicated, as calls for regulatory compliance, environmental stewardship and workers’ rights grow.

One farmer told Jesmer: “What stresses me out the most, is we get it from all sides,” she said.

With the 750 respondents, the surveys aim to drill deeper for short- and long-term solutions with questions about perceived stress.

They were organized by the Western Regional Agricultural Stress Assistance Program, or WRASAP, a coalition of agencies and universities from 13 Western states and four territories to address mental health and suicide among farmers. WRASAP and similar coalitions in other regions are part of the nationwide Farm and Ranch Stress Assistance Network, funded by the 2018 Farm Bill.

Among the findings:

—The top three reported stressors were workload, lack of time and financial worries, in that order, throughout the West.

—Farmers asked for resources to help with finances, relationships and sleep, among other issues.

—The youngest age group, 18–32 years, was the most likely to seek mental health resources through social media and most likely to want face-to-face counseling. Mental health support is simply more accepted among younger people, Jesmer said.

—Older farmers preferred online mental health help rather than in-person counseling. Professionals suspect that’s driven by stigma. Online appointments are private, but “everybody in town knows their pickup” if they park outside a therapist’s office, Jesmer said.

—Female farmers report higher levels of stress but die by suicide at a much lower rate than men. Female farmers have a similar suicide rate as the national average for women.

To read all the survey results, including data by state, visit: farmstress.us/wrasap-baseline-data-collection.

The survey also involved long interviews with farm operators that WRASAP officials are studying to find common themes. No report is available for those yet.

Workers feel stressed, too

Farmworkers are getting the message, too, though efforts to reach them are a little further behind, said Esmeralda Mandujano, an outreach specialist with the University of California, Davis.

Mandujano has been leading efforts to give the same survey to farmworkers, but she uses “promotores,” outreach workers who either volunteer or are hired with separate grant funding. Workers don’t tend to fill out surveys online but will participate face to face or by phone after a relationship has been established, she said.

That survey was still out as of late March, the deadline for this issue of Good Fruit Grower.

However, farmworkers have reported stress in other studies. In an overall health survey by UC Merced in fall 2021, 15 percent of workers reported feelings of uncontrollable worry, while 14 percent said they felt depressed or hopeless.

Mental health among farmers and farmworkers is linked, Mandujano said.

“If a farmer feels stressed, the farmworker will feel it, too,” she said.

When tragedy occurs at offices or schools, counselors show up to help colleagues and students cope and adapt. That doesn’t happen at farms, Mandujano said. Workers usually go straight back to work because fruit is ripe, and they need the paycheck to pay rent. Farm work is competitive. They think: “If I don’t get back to my job, someone else will.”

Still, workers often don’t complain about stress directly, said Mary Jo Ybarra-Vega, a mental health outreach specialist with Quincy Community Health Center in Central Washington. Instead, they discuss helicopter supervisors or bathrooms being out of toilet paper. Women tell her about neck pain while men show depression in the form of anger.

She also sees workers increasingly replacing energy drinks with meth or a drug-laced drink, called a “cometa,” to enable them to pick longer and faster. Some of them don’t know what they are drinking, she said.

Bring up the term “mental health” and the reaction is often “I’m not crazy,” said Ybarra-Vega, a licensed therapist.

However, Ybarra-Vega and Mandujano have noticed that stigma waning.

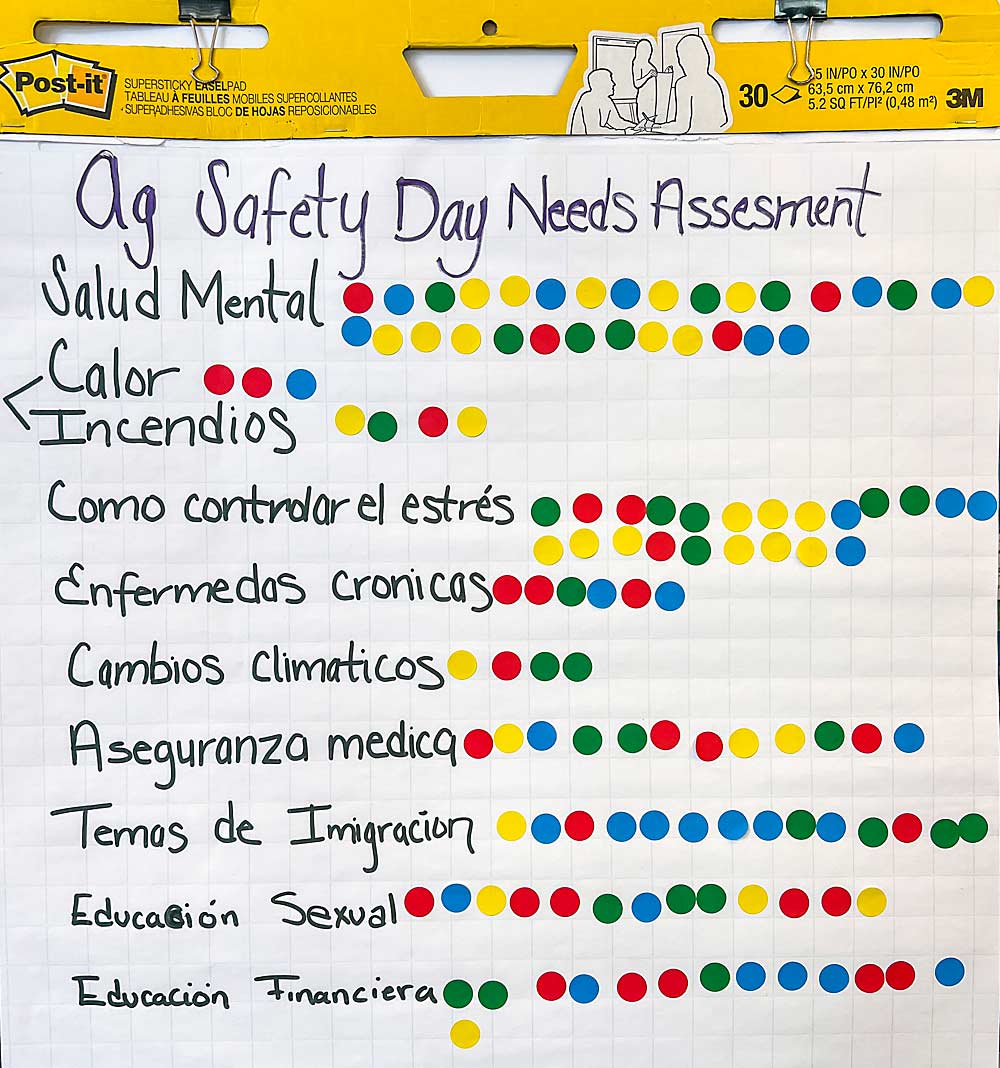

In February at an agricultural safety conference in Yakima, mental health and stress management topped the list of concerns in an informal needs assessment, while rooms were full for Spanish-language presentations about mental health. Crew chiefs have invited Ybarra-Vega to visit their workers.

She encourages supervisors to keep up with their training and executives to communicate with crew chiefs about stress and depression.

“You guys have the ability to give life or not,” she said.

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment