Joe Beaudoin of Joe’s Place Farms, an 80-acre u-pick farmer’s market in Vancouver, Washington, holds a Cameo apple damaged by brown marmorated stink bugs. He estimated that he lost most of his Granny Smith apples (about 3,000 pounds) to stink bug damage. (Courtesy Dr. Peter Shearer/Oregon State University)

Warning: The invasive brown marmorated stinkbug is headed your way.

The pest, already in more than 40 states, is rapidly spreading through the Pacific Northwest and had its first sighting in the Columbia Basin last year.

Dr. Nik Wiman, bearer of the sobering news, is sharing some of the latest research findings on the pest this winter during tree fruit talks in Washington State.

Photo Illustration: Brown marmorated stinkbug. (Courtesy Lynn Ketchum, Oregon State University)

The Oregon State University entomologist has spent the last two years working on a federally funded brown marmorated stinkbug project.

A team of 50 scientists from across the country is collaborating to develop management strategies to control the voracious pest.

Research on the West Coast is being led by OSU entomologist Dr. Peter Shearer. Wiman’s part in the project includes conducting statewide surveys for the pest; evaluating natural enemies, flight capacity, and population dynamics; identifying crops at risk; and figuring out which plants it prefers.

The far-reaching project also involves developing monitoring tools, attract-and-kill control methods, and biological control.

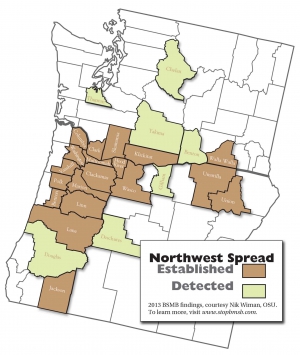

Wiman has followed the stinkbug’s march through Oregon, which has spread from its initial detection in Portland in 2004 to some 20 counties throughout the state following the major north-south and east-west highways (Interstates 5 and 84).

In 2011, homeowners in the greater Portland urban area began complaining of brown marmorated stinkbug infestations in their homes and gardens, he said, adding that OSU received funding for a statewide survey in 2012.

“We found major movement of the pest,” said Wiman. Brown marmorated stinkbug was found in 240 sites, from southern Oregon to the Columbia Gorge, and in Umatilla County. The pest was also detected in Washington’s Yakima County.

For the first time, the pest was detected in commercial farms (hazelnuts, tree fruit, wine grapes, and blackberries) in Oregon’s Willamette Valley. All of the farms were close to urban areas.

Since 2012, the stinkbug has continued its spread.

“In 2013, it got a lot worse, and we’re seeing more established populations, both in Oregon and Washington,” Wiman said. The pest is confirmed in Walla Walla, Washington, and in drier locations of Oregon, including The Dalles, La Grande, and Hermiston. Wiman believes it’s very likely to be established in the Tri-Cities area of Washington.

California officials began looking for brown marmorated stinkbug last year and found a significant population located in Sacramento.

A detection in Hermiston is the first indication of its movement into the Columbia Basin, a desert climate with irrigated agriculture, he noted. That’s significant because past detections on the East Coast and in Oregon’s Willamette Valley were near mixed wood forests, riparian zones, and habitat similar to the stinkbug’s native environment in Asia.

Urban risk factor

Last year saw the first documented report of economic damage to a commercial grower. A Vancouver, Washington, grower farming 80 acres of tree fruit and vegetables had significant damage in his Asian pears, Granny Smith apples, and several vegetable crops.

“The Vancouver farm is an extremely urban farm,” Wiman said. “The urban risk factor has a lot to do with that farmer having economic damage.”

Most farms in the Willamette Valley where the pest has been found are also near urban areas, though not as close as the Vancouver farm.

“Humans are a big factor in the stinkbug’s dispersal,” he said, adding that the stinkbug hitchhikes in moving vans, recreational vehicles, lumber shipments, freight trains, and ships.

Using flight mills (a device attached to bugs allowing them to fly in continual circles), OSU researchers found that the brown marmorated stinkbug is a good flier. Most can travel about 15 miles within a 24-hour period.

“A few flew 50 miles in a 24-hour period, so they don’t need a lot of assistance from us,” Wiman said.

The pest attacks a wide range of crops, damaging fruit and vegetables with its sucking mouthparts that secrete saliva while the insect sucks up the plant’s juices. Fruit flesh is discolored; dimpling and bruising can also occur.

Wiman found it has a similar appetite on the West Coast as in the Mid-Atlantic region, where it has spread since the first U.S. detection in Pennsylvania in 1996. In the Willamette Valley, stinkbug damage has been observed on apples, Asian pears, cane berries, blueberries, and hazelnuts.

Though tree fruits are not a big crop in the Willamette Valley, hazelnuts are. Oregon produces 99 percent of the nation’s hazelnut crop.

“The stinkbug has no problem feeding through the shell of the nut and reaching the kernel,” he said.

Crops like wine grapes and mechanically harvested bush and cane berries also face potential contamination issues from the stinkbug’s odor, a smell that some liken to cilantro.

OSU’s food science department studied contamination in Pinot Noir wines. When given three blind samples of Pinot Noir (one spiked with brown marmorated stinkbug), tasters could easily pick out the spiked sample. “It wasn’t that it tasted bad,” Wiman said, “but certain wine flavors were masked by chemical reactions from the stinkbug.”

One of the problems in managing brown marmorated stinkbug is that it has a long list of host plants in the United States. Two of the stinkbug’s favorites—tree of heaven and Himalayan blackberry—are commonly found on both sides of the Cascade Mountains in Washington and Oregon.

Tree of heaven, in the Pacific Northwest since early railroad days, is found alongside train tracks and often is the only green plant around. Himalayan blackberry is loved by both the stinkbug and spotted wing drosophila, another recently arrived pest gaining a foothold in U.S. fruit-producing regions. The invasive blackberry plant grows like a weed in many areas when left unchecked.

Other common plants in Northwest forests that Wiman has found serving as hosts include dogwood trees, several maple species, and English holly.

With the recent discovery of brown marmorated stinkbug in the Columbia Basin, Wiman said it’s an open question about what the pest will do in a dry environment. “It remains to be seen how the pest will do in our dry deserts, with its limited amount of vegetation and number of alternate hosts, massive farms, and few people.”

But if it’s not in your area yet, know that it’s likely coming. •

Leave A Comment