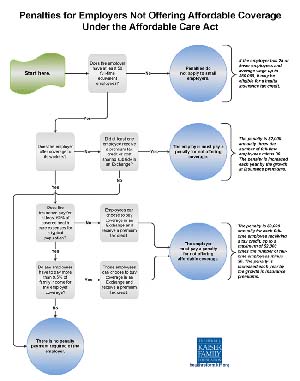

Click image to read the chart. The Affordable Care Act does not require businesses to provide health benefits to their workers, but larger employers face penalties starting if they don’t make affordable coverage available. Enforcement of those penalties will begin in 2015, a year later than originally scheduled. This flowchart illustrates how those employer responsibilities work. (Graphic from the Kaiser Family Foundation)

Do you have to provide health insurance for the employees on your farm?

The answer to that is pretty straightforward. If you employ 50 or more Full-Time Equivalents (FTE), you must offer full-time employees health insurance under the new Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act or pay a penalty.

If you employ fewer than 50 FTEs, you do not have to.

If you don’t know exactly how many FTEs you employee, but it may be in the vicinity of 50, then you have some work to do to figure it out. The magic number is 50. And there are specific rules for counting full-time employees, part-time employees, and seasonal employees. More on that later.

Also remember. Under the new health care law, every legal resident of the United States (working on U.S. soil, not elsewhere) must have health insurance or pay a penalty that will be collected by the Internal Revenue Service at income tax time. Whether people buy it for themselves or get it through their employer or a public program like Medicare or Medicaid, they must have it. There is no “forgiveness” if a person refuses to buy health insurance and then incurs catastrophic medical bills.

The law applies to all employers—private, non-profit, churches, or government.

This Good Fruit Grower reporter spent more than three hours, with about 25 fruit growers, in a seminar that explained it all in bewildering detail. Michigan State University agricultural economist Dr. David Schweikhardt and MSU farm management agent Dr. Adam Kantrovich had been traveling the state of Michigan explaining how the law works, and their audience that evening comprised fruit growers in north central Michigan near Hart.

The presenters made it clear from the start: Their goal was to explain the requirements of the law. “Don’t shoot the messenger,” Kantrovich said. “MSU is not choosing a side.”

“Approach this as a labor management issue,” Schweikhardt said. Forget politics for now.

Of course, the law, passed along partisan party lines in 2010, has been controversial. The U.S. House of Representatives has tried to kill it nearly 50 times. The roll-out of the Web site that was supposed to provide everyone easy access to the Health Insurance Marketplace, failed in October, making it unclear whether the provisions can be implemented on the original schedule.

Adoption was further complicated by uncertainty. Would the law even survive to be implemented?

Bottom line, however, is that by January 1, 2014, everyone in America is supposed to have a health insurance policy. The enrollment period for 2014 closes March 1.

For employers, there are three key questions, Kantrovich said:

1) What is my average monthly number of workers?

2) What are my options for providing health insurance?

3) Am I eligible for a Small Business Health Care tax credit that will help pay the premiums?

How many workers?

As an employer, you also need to figure out:

• How many employees you have. Start counting with full-timers.

• How many employees provide 30 or more hours of service (including sick time and vacations) a week for 120 days or more a year. Do a head count. Include family members in the head count.

• How many part-time employees you have. Count up the number of hours part-timers work per week and divide that by 30 to determine how many full-time equivalent employees you have.

If you have workers who are independent contractors (perhaps you hire a pruning service) or are “leased” through a staffing agency, they do not count as your employees. Be careful, Kantrovich advised. Staffing agencies must be licensed and certified, and independent contractors must qualify to get form 1099, not W-2—and be wary of the IRS’s anti-abuse rule for anyone attempting to skirt the law.

How many seasonal employees do you have? A seasonal employee is one who works no more than 120 days a year. These are exempt and may not get counted, as long as you do not get to 50 FTEs or more or, if you do, it is for no more than 120 days throughout the year.

If you get to 50, you must provide health insurance. Less than that, you do not.

Remember, when counting part-time employees, the number helps determine whether you must provide insurance but, no matter the number, you do not need to provide health insurance to the part-time employees. Conceivably, you could have thousands of employees and thousands of seasonal workers, and your official count could be one or two. Remember, count yourself or any family member who provides labor.

Kinds of policies

Employers with a total of at least 50 full-time equivalent employees must either offer an affordable health plan that provides a minimum level of coverage to full-time employees or pay a penalty—the Employer Shared Responsibility payment.

If you choose to provide health insurance—either because you have to or you want to—you, as an employer, don’t have to pay the full premium for your employees. You can charge the employee partly for their coverage, an amount up to 9.5 percent of his or her “household income,” but since you can’t really know that, Kantrovich said, the IRS requires employers to use W-2 wages that you actually pay as the base for calculating. You can charge fully for the cost of the premium for his or her spouse and dependents, and you need not offer insurance to the spouse at all.

That 9.5 percent figure defines “affordable” in the act’s name. While 9.5 percent may seem like a lot of money for health care, remember that a key reason for passing the law was that health care costs were expanding uncontrollably and now consume nearly 18 percent of all the dollars generated in the U.S. economy. That is nearly twice what we pay for food.

“Affordable” has a second meaning. There are income-based subsidies—tax credits—for individuals and for employers to help them buy or provide health insurance. When a person goes to the Web site (www.healthcare.gov) and enters personal information about household income, the insurance provider will immediate calculate the amount of the subsidy and or tax credit the buyer will receive.

To be eligible for the tax credit, policies must be purchased through the Web site, the Health Insurance Marketplace and, for employers, through the Small Business Options Program (SHOP) through the Marketplace Web site. You cannot go through an insurance agent that does not use the Marketplace and receive the tax credit.

Note the terminology, “offer” insurance. If you employ 50 or more FTE’s, you must offer the insurance, but the employee need not take it. He or she can shop for insurance plans as well, but if the employee refuses the employers’ “affordable” offering, no tax credit is allowed.

Patient protections

The “patient protection” part of the act’s full name is more complex.

Insurance companies can no longer use “preexisting conditions” in determining how much they will charge for a policy.

The only factors they can use in pricing their policies are age of the insured (and that is limited to a 3:1 ratio), whether the person smokes (also limited, to 1.5 times the base rate), and where the insured person lives.

Children now must be allowed to remain on their parents’ insurance policy until age 26.

Insurance companies may not place lifetime caps on how much they will pay for the health care of the insured people.

There are also limits on how much a policyholder will have to pay for a deductible. Deductibles are pretty standard in all policies, but there is a cap. The maximum deductible a person may have is $6,350 a year for an individual, and $12,700 for a family plan.

Insurance companies are mandated to pay out at least 80 percent of the money they collect in premiums for actual payments for health care, and if they do not, they must issue a rebate to each policyholder. This puts somewhat of a cap on salaries of insurance company executives, administrative costs, and payouts to stockholders in the company.

Companies also must offer policies that meet minimum standards. Qualified Health Plans offered by insurers on the Health Insurance Marketplace must contain “Essential Health Benefits” that include these ten categories:

Ambulatory patient services; emergency services; hospitalization; maternity and newborn care; mental health and substance use disorder services, including behavioral health treatment; prescription drugs; rehabilitative and habilitative services and devices; laboratory services; preventive and wellness services and chronic disease management; and pediatric services, including oral and vision care.

Levels of policies

Insurance policies that meet the criteria as Qualified Health Plans are described according to four major levels of coverage—the amount of deductibles and co-pays.

Bronze policies may require the insured to pay 40 percent of the health costs in deductibles, co-payments and out-of pocket expenses (60/40 plans). Silver plans require 30 percent payments by the insured (70/30 plans); gold plans 20 percent (80/20 plans), and platinum plans 10 percent (90/10 plans). There is also a catastrophic category with very high deductibles available for some people under 30 or with certain hardship exemptions.

In general, the more you are willing to pay from your own pocket, the lower the premium. Bronze policies are the cheapest.

When you shop for insurance on your state’s Marketplace, you’ll see the health plans organized first by metal level, then by brand (Blue Cross, Cigna, Humana, Kaiser, United, etc.), then by type of health plan, such as HMO (Health Maintenance Organication), PPO (Preferred Provider Organization), POS (Point of Service), or high-deductible plans with a health savings account.

While most states do not offer their own Marketplaces, insurance plans are still offered within state boundaries, not across state lines.

Try it out

While Michigan is one of the majority of states that did not elect to set up its own Health Care Exchange and instead went with the federal system, the state’s Department of Insurance and Financial Services offers a summary of the Qualified Health Plans and a list of rates for individuals seeking to buy health insurance. It is quite a useful tool for anyone in any state and can be found at www.michigan.gov/difs.

Some 14 companies are offering insurance in Michigan, and premiums are listed in a table for individuals of various ages and by tobacco use. There is also a premium calculator showing the range of premiums by location, metal level, number and age of adults and children in the household, and annual income—for tax credit purposes.

More provisions

There are thousands of provisions in the law. Some other important ones are:

• If an employer has 25 or fewer employees whose average wage is less than $50,000, the employer may be eligible for a tax credit if he or she provides insurance.

• Employers who should provide insurance but don’t will pay a penalty—if at least one employee goes to the Health Insurance Marketplace, buys his or her own policy, and receives a tax credit against the premium. That penalty is $2,000 per full-time employee minus 30. For example, if you have 50 employees, you pay $2,000 times 20—per year. It will be due in monthly installments to the IRS.

The penalty can actually seem stiffer if the employer offers insurance that is not “affordable.” That penalty is $3,000, but only on employees who buy coverage in the Health Insurance Marketplace and get a tax credit, and the penalty is limited to $2,000 times number of full-time employees minus 30.

Individual mandate

If you are a farmer who is self-employed—even if you don’t hire a threshold number of employees—you, your family, and your workers are all subject to the Individual Shared Responsibility requirement—that is, the “individual mandate” to carry health insurance.

People who are on Medicare or Medicaid or other public health coverage program, such as the Children’s Health Insurance Program or TRICARE, will continue to obtain health care coverage in that way.

The penalty for not having insurance is the greater amount of either:

A flat dollar amount of $95 for the taxable year 2014, $325 for the taxable year 2015, $695 for the taxable year 2016, and $695 plus cost of living adjustments in all taxable years thereafter, or;

A percentage of the modified adjusted gross household income (1.0 percent for the taxable year 2014; 2.0 percent for the taxable year 2015; and 2.5 percent for taxable years 2016 and thereafter) This penalty can be assessed individually against all individuals in the household who should have had insurance (but at half rate for those under age 18).

Links and Web sites

The most important site for everyone is www.healthcare.gov. That is how individuals and employers access the Health Insurance Marketplace and actually sign up for health insurance.

Other helpful Web sites include:

www.irs.gov/uac/Small-Business-Health-Care-Tax-Credit-for-Small-Employers

www.firm.msue.msu.edu click on Affordable Care Act to see fact sheets developed by Kantrovich and Schweikhardt.

Leave A Comment