Fruit growth can be broken down into three parts of the fruit — the seed, the stone and the flesh — that develop separately over time. These stages of development fit in with other growth patterns of the tree, such as growth of new shoots and roots.

An understanding of the development of these parts of the fruit will help you to successfully use regulated deficit irrigation, to time your thinning and to maximize the size of fruit at harvest.

Fruit growth stages

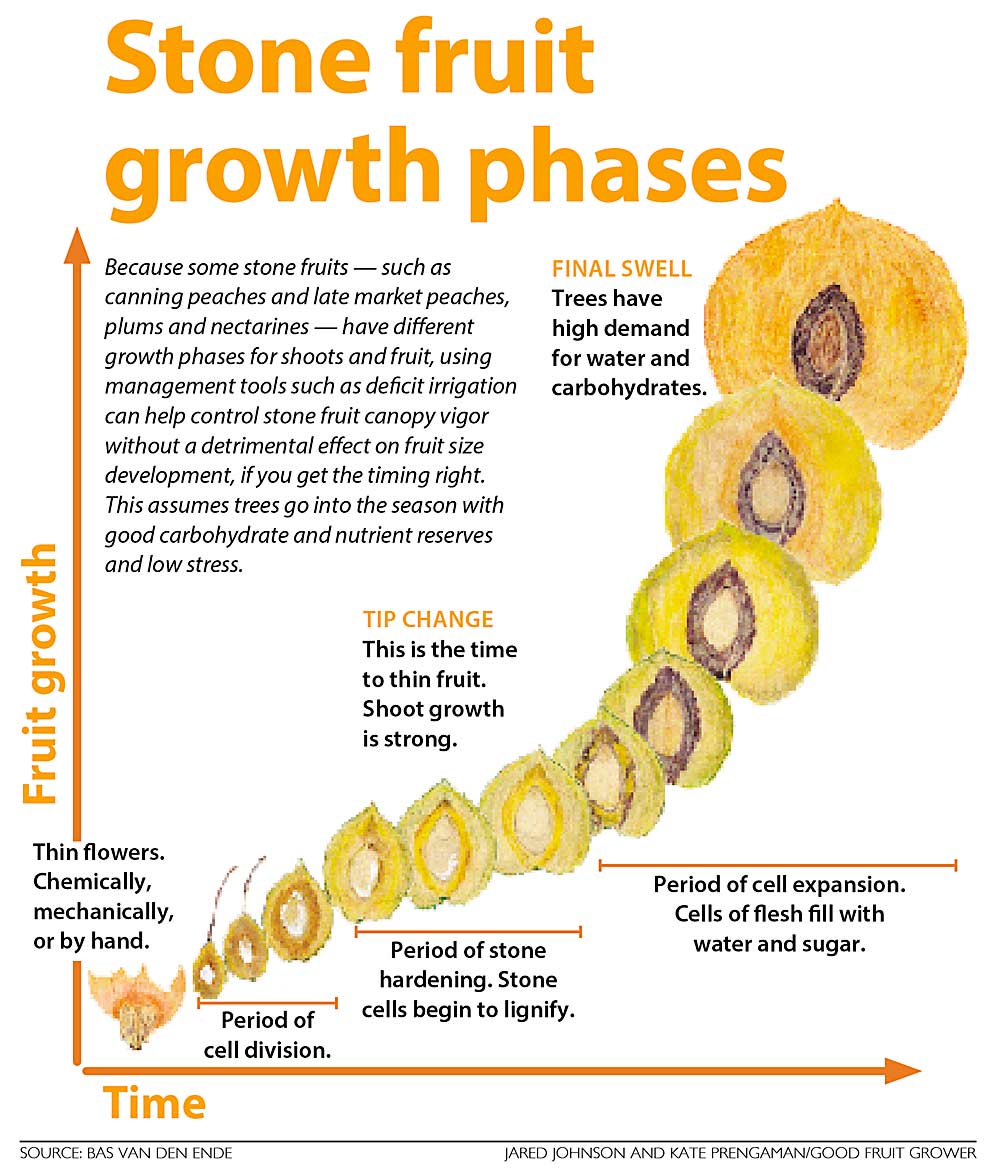

Cell division: After flowering and fruit set, there is a period of several weeks when cells are formed in the flesh and stone.

Stone hardening: Following the period of cell division, the tree will look after the reproductive part of its fruit, namely the seed. A hard shell around the seed, called the stone, protects the seed from being damaged. As the seed grows to its full size, the stone hardens (lignifies) around the seed.

Cell expansion: When the stone has lignified and the seed is fully developed, the tree will fill the cells of the flesh with sugar and water. This period of cell expansion is usually much longer than the period of cell division.

Final swell: Cells expand rapidly, especially toward the end of the growth cycle when harvest time approaches. The tree’s demand for water is high.

By cutting several fruit through the suture line, using anvil-type pruning shears, you can follow the growth cycle of your fruit and determine when you should apply regulated deficit irrigation, where applicable, and also when you should start and finish thinning.

You can also determine when the fruit reaches the final swell stage.

Growth stages guide RDI

Many orchardists have heard of regulated deficit irrigation (RDI). RDI can save water and money by reducing irrigation and pruning. Although trees under deficit irrigation are purposely stressed for water, as the term describes, RDI is not a haphazard neglect of irrigation but rather a carefully planned irrigation strategy.

RDI aims to manipulate the seasonal growth pattern of the trees and to channel more tree resources into fruit rather than into shoot growth.

With some fruit crops, such as canning peaches and late-maturing market peaches, nectarines and plums, fruit growth and shoot growth are out of phase — that is, they grow at different times. Early in the season, shoots grow rapidly and fruits grow slowly; whereas in the six to eight weeks prior to harvest, fruits grow rapidly and shoots have stopped growing.

RDI can be applied to these fruit crops, as well as pears, because the growth of new shoots can be controlled without affecting the growth of fruit. When fruit trees are temporarily deprived of adequate water, fruit growth slows down. On the resumption of ample irrigation, growth accelerates.

Under RDI, the level of irrigation is decreased during the period of fast shoot growth by cutting back (25 to 30 percent of evapotranspiration) on the quantity of water delivered but maintaining irrigation frequency. At the start of fast fruit growth, optimum irrigation levels are resumed.

This approach not only decreases shoot growth and the need for summer and dormant pruning, it also increases fruit size and yield. The phenomenon associated with RDI is compensatory growth — when the concentration of sugars continues to accumulate and increase within the fruit during the period of water stress. At the end of the moderate period of water stress, the fruit absorbs more water to achieve the normal balance between sugars and water. This has often resulted in bigger fruit at harvest compared with fruit where RDI has not been used.

With peaches, nectarines and plums that mature early in the season, as well as cherries and apricots, fruits and shoots grow at the same time, so RDI is not recommended.

Thinning fruitlets or flowers

Thinning fruitlets is one of the most expensive and labor-intensive exercises in stone fruit production. Thinning fruitlets also exacerbates the incidence of split stone.

More and more stone fruit growers are starting to realize that size of fruit at harvest can be greatly improved by thinning flowers by hand, chemically or both, and, if necessary, by following up with a quick thin of fruitlets. Again, understanding the stages of development can optimize thinning.

Varieties that mature early and/or are hard to size both benefit from flower thinning.

To thin flowers and fruitlets to obtain the sizes of fruit that the markets demand, you must know how the fruit of different varieties behave. Fruit set, premature fruit drop and “doubling” are factors you must put in the equation when you try to regulate your crop.

By periodically examining your stone fruit, you take the guesswork out of managing your orchard.

—by Bas van den Ende

Leave A Comment