Lynn DeVleming and Rick Wasem are co-owners in Basalt Cellars, a Clarkston, Washington winery. They are standing in Wasem’s vineyard that overlooks the Snake River.

When Rick Wasem of Basalt Cellars started planting wine grapes in 1996 in Clarkston, Washington, he not only established the state’s easternmost vineyard, but began the process of bringing award-winning local wines back to what was once a thriving wine region.

In the late 1800s, the area was a significant grape region, with grapes grown for juice, wine, and processing. The cities of Clarkston and Lewiston, located in two separate states and divided by the Snake River, jointly have a population of around 60,000. Clarkston is on the Washington side, Lewiston in Idaho.

(Aurora Lee/Good Fruit Grower illustration)

Robert Schleicher was an early grape pioneer, planting 130 acres of wine grapes in 1883 near Lewiston and receiving awards from wine competitions in New York, Missouri, and Oregon.

Another pioneer was Robert Schafer, who planted 60 acres of grapes in Lewiston in 1896 and had one of the state’s earlier wineries in Clarkston, operating from 1906 to 1911, according to Ron Irvine’s The Wine Project: Washington State’s Winemaking History. An area of Clarkston is still called Vineland, a throwback to its grape-producing days.

But because Idaho was an early adopter of Prohibition laws (Lewiston voted to be a dry town in 1910), most of the grapevines were pulled out and replaced with tree fruit orchards well before the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution went into effect in 1920.

Wasem’s grandfather had a vineyard in Clarkston in the 1910s and grew juice grapes to process in his cannery. His grandfather did not “officially” make wine due to his Christian Science religious affiliation, said Wasem, but winemaking equipment was housed in a portion of his barn.

Decades following the end of Prohibition, Washington State University’s Dr. Walter Clore, who traveled throughout the state searching for suitable wine grape sites, came to Clarkston and Lewiston. Clore convinced Lewiston meteorologist Robert Wing to plant a small trial vineyard on the Lewiston side in 1972.

“Their conclusion was that the area still was a great place to grow wine grapes,” said Wasem.

Wasem is a Clarkston pharmacist by day, but he made wine in his basement for years before launching Basalt Cellars. “Winemaking is in my genes,” he said, noting that his grandfather made wine, as do relatives in Germany who have been tending grapevines for 300 years and have a 100-year old winery. He also has cousins working in northern California wineries. “I think winemaking is a genetic thing with me.”

In the 1990s, he found the perfect site for a vineyard and began transforming acres of noxious star thistle and cheat grass into a small vineyard. Thus far, he’s planted three acres with Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Syrah, Chardonnay, Petit Verdot, Malbec, and Zinfandel. He’ll have about six acres when the parcel is completely planted.

Steep, low-vigor site

Elevation of his vineyard, which overlooks the Snake River, is 1,100 feet at the top, sloping downward to 925 feet. Because of the steepness, he had to terrace most of the block. “It’s so steep that for the most part, everything has to be done by hand,” said Wasem, adding that spraying is done with an ATV.

“The slope provides great air drainage, and the vineyard receives early morning sun to warm it up quickly,” he said. “The cold air just slides down to the river. I don’t have any flat ground, low pockets, or any place for the cold air to stop.” He’s not lost any vines to winter kill, although he had a light crop one season due to bud damage from frost in early May.

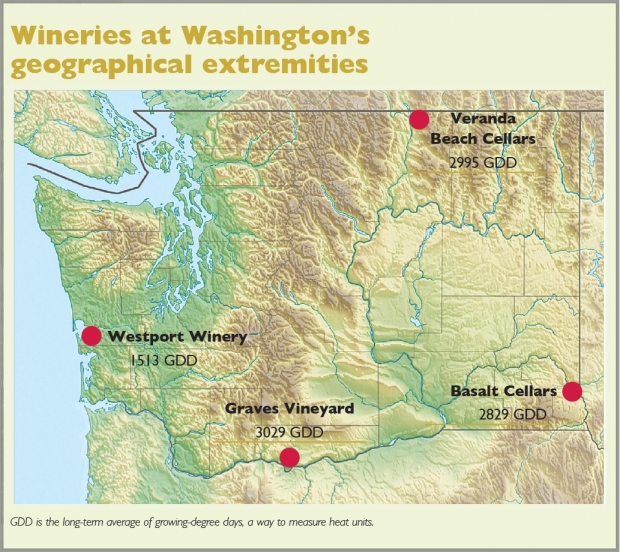

The average growing degree-days for the vineyard, a measure of the heat units, is 2,829. Last year was a very warm season, and he recorded 3,287 GDD.

The top layer of soil, wind-blown loess, is a sandy loam. Underneath the loess is alluvial sand, gravel, and sedimentary material deposited from the Lake Bonneville Flood and Missoula Floods that occurred during the Ice Age.

“The site is very low vigor and the climate quite dry, receiving annual rainfall of 10 to 12 inches,” Wasem said. He controls canopy growth through irrigation, but notes that between the sandy loam soil and riverbed rocks underneath, “irrigation water just disappears.”

The high soil pH of 8.0 to 8.2 limits uptake of some micronutrients important for fruit development and affects fruit set. “Clusters are generally not as full as those in more vigorous sites, and berry size is naturally on the small side,” he explained. “But there’s usually no need for color thinning.”

He adds composted horse manure annually to help improve organic matter in the soil, and he also uses foliar sprays to add trace minerals.

Clarkston’s only winery

Wasem and winery partner Lynn DeVleming opened Basalt Cellars in 2004 to bring locally produced wine back to the region. Although DeVleming completed the viticulture and enology program at Walla Walla Valley Community College, Wasem said that because of his pharmacy and chemistry background, he became winemaker “by default.”

In addition to Wasem’s small vineyard, DeVleming also has two acres of wine grapes used in the Basalt Cellars wines. “Although we are slowly growing our production of estate wines, thus far, most of our wines are from grapes sourced from Walla Walla, Sagemoor Vineyards, and the Yakima Valley,” he said. “Some of our vines are still young, and we don’t want to push them to produce too soon.”

In the first year of business, Basalt Cellars produced 1,500 cases. Buoyed by great reviews and awards, they quickly ramped up production to 2,200 cases.

“But we discovered that selling 2,200 cases in Clarkston was difficult,” he said. “We’re the only winery in town doing tastings and tours, so there’s not a hub of wineries. Without outside distribution, it was hard to market all of the wine.”

Wasem and DeVleming have since scaled back to 1,800 cases for annual production, a more manageable volume to sell through their doors. Seventy percent is sold through direct sales at the winery and their wine club. The rest is sold to local restaurants and in regional markets.

Wasem has learned that most distributors are not willing to handle small wineries unless the winery accepts discounts. “We’re not ready to start doing the discount thing.”

Surprisingly, they sell quite a bit of wine to California. “It’s our biggest state for shipping,” he said, noting that shipments are usually repeat buys from customers who visited the winery.

Wasem said that in addition to wine competitions in the Pacific Northwest, they also enter several judgings in California. Wine competitions like those held by the San Francisco Chronicle, Sunset magazine, and Grand Harvest in Sonoma help generate publicity in California. They are most proud of awards for best of class and double gold for their 2008 Cabernet Sauvignon from the Grand Harvest competition. •

[…] Ironically, there are problems with the other AVA petition involving Idaho. The proposed Lewis-Clark Valley AVA involves two states — Washington and Idaho — but the ongoing debate involves removing about 57,000 acres from the Columbia Valley AVA. That would require winemaker/grower Rick Wasem of Basalt Cellars in Clarkston, Wash., to use Lewis-Clark Valley, rather than the well-known Columbia Valley AVA, on the label of his wines, including those made using fruit from his estate vineyard. […]