Organic agriculture, aside from reduced exposure to pesticides, doesn’t necessarily translate into better working conditions for farmworkers, a University of California study found. Most of the attention placed on organic agriculture, one of the fastest growing segments of the food system, is on the consumer benefits of produce free of synthetic chemicals, and benefits to farmers of higher prices.

But what does organic agriculture mean to the farmworkers who work on organic farms? Do farmworkers benefit if they work on organic farms? Is organic agriculture more “socially sustainable” than conventional agriculture? The implications of organic agriculture for farmworkers were the focus of a study by the UC Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education Program based in Davis.

Gail Feenstra, a sustainable agriculture food systems analyst; Christy Getz, assistant Cooperative Extension specialist at UC, Berkeley; and Aimee Shreck, a postdoctoral researcher for the sustainable agriculture program, co-authored the study. “The results of the study were surprising,” Shreck said.

“We learned some big lessons about the diversity within the category of organic agriculture. Organic farmers can be large, with mixed acreage of conventional and organic, and they can be small in scale. You can’t make broad generalizations.” They also found great diversity in the working conditions of farmworkers employed in organic agriculture.

Misperception

There’s a misperception that because organic farming standards prohibit the use of many pesticides and organic farmers are perceived as social activists, that the working conditions of farmworkers are better than for those working in conventional agriculture.

In recent years, the organic community has debated incorporating social criteria into organic standards and certification requirements. At the international level, the International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements adopted a new chapter on social justice for its basic standards, which are standards that IFOAM-accredited certifiers must comply with, according to the study’s authors.

The California Certified Organic Farmers and the California Sustainable Agriculture Working Group have also discussed social standards, but the ideas haven’t been seriously considered. The official definition of organic agriculture under the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s national organic program does not include any certification criteria concerning farmworkers’ rights or their working conditions.

The study sheds light on the term organic farmer and what that means, Shreck explained. There are many different dimensions to organic agriculture. It also provides insight related to social certification and organic agriculture in California. She noted that there’s been little attention given to farmworkers involved in organic agriculture.

Insight

The project included in-depth interviews of those involved with organic agriculture in California—farmworkers, growers, and representatives of the organic community. Questionnaires were also sent to a random sampling of organic growers. Out of 500 surveys mailed, nearly 200 were completed and returned.

The majority of those responding to the survey were growers who farm 50 acres or fewer and report less than $50,000 in annual sales. Three-quarters of the farmers market ten or fewer crops, with just over 30 percent growing only one crop for marketing purposes.

Two-thirds of the responding farmers hire workers in addition to their own families. The study found that though organic products typically bring higher prices, many small- and medium-sized farmers can’t afford to be “socially sustainable.” It’s hard to expect them to provide things like health insurance for their workers when they don’t have health insurance for themselves, Schreck said.

Though safe, fair, healthy, and equitable working conditions for hired labor are considered central to agricultural labor certification programs, the study found little support for adding social certification standards to current organic standards. More than half the growers surveyed opposed such a requirement. Most respondents felt that requiring health insurance or living wages would not be economically viable given current market conditions.

Survey results

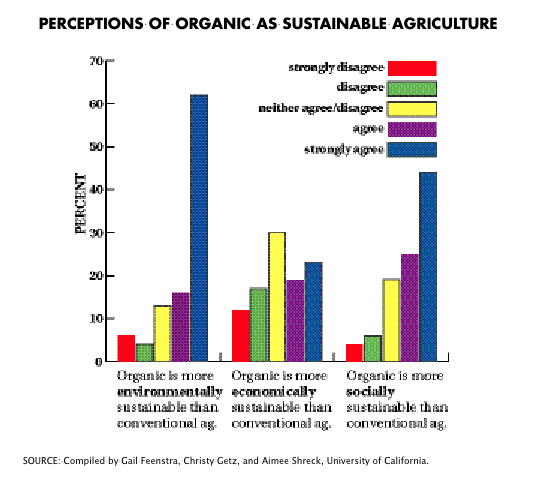

The survey found that while a fairly large majority of farmers said that organic was more environmentally sustainable, less than half think that organic is more economically sustainable. “Remarkably, about 40 percent of the respondents ‘strongly disagree’ with one of the proposed requirements, to ‘respect farmworkers’ right to bargain collectively,’ even though it is already required by California law

(under the Agricultural Labor Relations Act of 1975),” Getz said. In-depth interviews with organic growers did highlight a number of exceptions to the survey results, Shreck noted.

The authors found farmers whose atypical practices demonstrate that an organic production system can be environmentally, economically, and socially sustainable. They will be looking more closely at these examples to see what can be learned from the farmers’ practices. “The study showed that farmworkers need to be brought into the organic equation,” Shreck said.

Leave A Comment