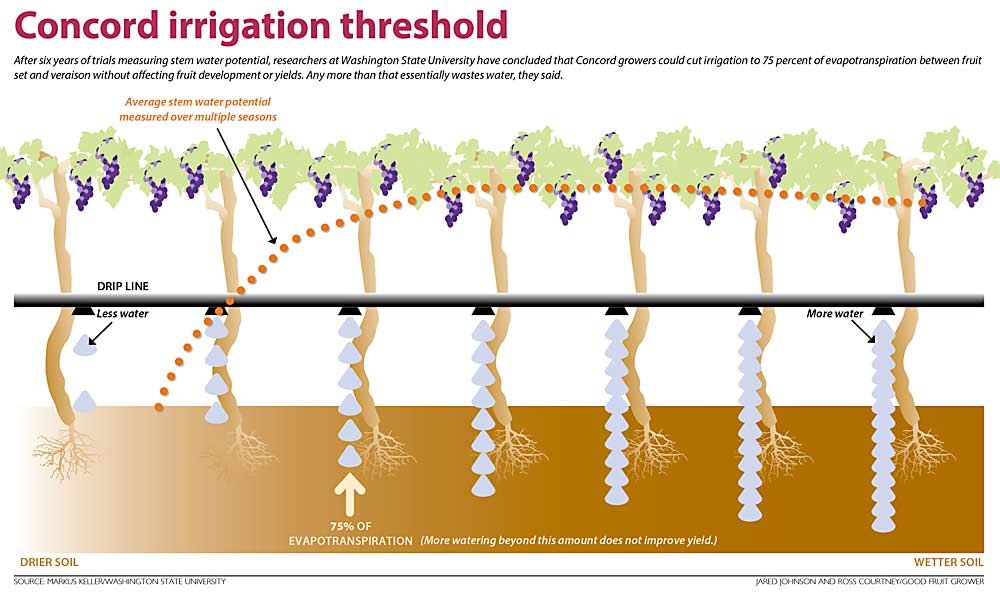

Graphic: Jared Johnson and Ross Courtney/Good Fruit Grower)

Markus Keller, a Washington State University viticulture professor, is convinced deficit irrigation will not hurt yields or crop load in Concord juice grapes.

The growers he works with are convinced, too, but Keller doesn’t expect them to change right away. They haven’t needed to, so far.

“Most juice grape growers shy away from deficit irrigation for fear of reducing load,” he said.

Deficit irrigation is common in wine grapes, where growers use strategic water stress to coax certain characteristics out of grapes, for more complex flavor in the wine they make. Juice growers just want to deliver as much volume as possible with the minimum required sugar levels — usually easy to reach in sunny Eastern Washington. No nuance necessary.

“With Concords, it’s all about tonnage,” said Keith Oliver, a manager at Olsen Bros. Ranches near Benton City.

However, six years of trials at WSU’s Roza research vineyard in Prosser has convinced Keller that Concords can still get their tonnage with less water than growers typically apply. But growers don’t see any reason to cut back unless they have a drought.

Saving water would be great in a shortage. Until then, they say, it makes sense to err on the side of caution.

“It’s not a problem to overirrigate Concords,” Oliver said. “Doesn’t hurt the crop.”

Ryan Schilperoort, a Sunnyside grower who has hosted some of Keller’s other irrigation trials, felt the same way.

“I believe what Markus is saying, I just haven’t had to do it yet,” Schilperoort said.

After Washington’s 2015 drought, Schilperoort switched from rill irrigation to drip irrigation, based on Keller’s trial results. His farm lies in an area with junior water rights, meaning his allotment is curtailed before those in older irrigation districts with senior rights.

While water supplies have been sufficient since, Schilperoort also likes the fertigation benefits of drip irrigation.

Other growers have made the switch to drip over the years, as well, he said.

Richard Hoff, the viticulture director at Mercer Canyons, plans to experiment with deficit irrigation after his juice vines reach maturity. The company, known for wine grapes, tree fruit and vegetables, is planting about 250 acres of juice grapes in the Horse Heaven Hills, south of the Yakima Valley.

“I plan to play with it,” said Hoff, who studied under Keller’s tutelage at WSU.

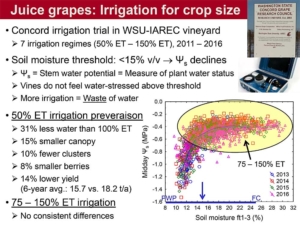

Keller began his trial comparing different levels of irrigation to a control block receiving 100 percent of evapotranspiration. Growers convinced him to bump the control up to 150 percent, more than replacing what water the plant loses, because that’s what they usually do.

Keller found that 75 percent of evapotranspiration is the magic number. Concord canopy development, fruit composition and yields improve with more water until that point, then level off. Cutting back even more will indeed affect fruit development, he said. Going beyond 75 percent is wasting water.

Specifically, his findings show that water cutbacks between fruit set and veraison offer the most water savings, because that’s when days are hottest and longest.

“That, of course, is exactly what the growers are afraid of,” he said.

Note: The researchers applied the various irrigation levels during different periods of the growing season and then watered enough to saturate the soil the rest of the year. Thus, 75 percent of evapotranspiration came out to roughly a 20 percent annual water savings.

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment