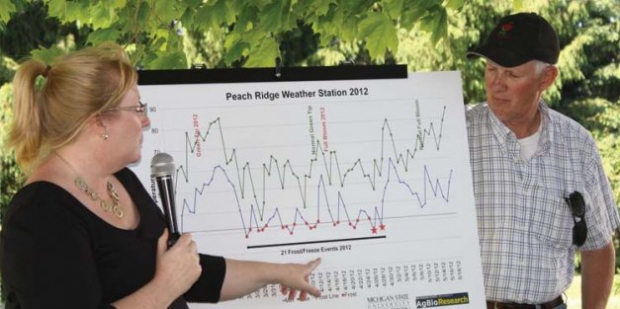

Phil Schwallier and Amy Irish-Brown have good records showing Fruit Ridge weather this spring. Growers can use this data to evaluate what happened in their orchards.

Photo by Richard Lehnert

While scientists warn that extreme weather events will become more common as carbon dioxide levels continue to build in the atmosphere, Great Lakes region fruit growers hope this year’s freeze event is one of those once-in-a-hundred-years events and not something to expect repeatedly or even again in their lifetimes.

“If this were going to happen once every five years, we’d have to get out of the fruit business,” said Mike Wittenbach, who grows 225 acres of apples near Belding, Michigan, with his father, Ed. “My grandfather and great-uncle talk about what happened in 1945, and we’d like to think these things don’t happen very often.”

He recalls hearing their stories about picking a bushel of apples off the top of a 30-foot-tall tree—but Mike isn’t planning to go back to seedling rootstocks to get treetops searching for warmer air.

One thing Mike has learned is the value of wind machines. “We have 12 now, and we’re about 70 percent covered. We need more. We have about 25 percent of a crop, and we’d have had 5 percent without them.”

Still, he estimates it cost him $30,000 to run his 12 machines for 18 cold April nights.

The cold winds that came with the freezes during the last weekend of April in Michigan this year cut the effectiveness of the wind machines, he said. “They weren’t a silver bullet this year,” he said. “They helped; irrigation helped.”

Mike figures that a wind machine should be helpful within a radius of about 350 to 450 feet. With the winds from the north this year, he said, the area covered was an oval shape extending from about 100 feet north of a wind tower to 300 to 350 feet southwest.

“It’s pretty much location. On the south side of wind machines, we got fruit.”

Wittenbach has also looked at varieties. “Variety matters very much. We have more Galas and Ruby Jons, which are much later blooming, and our earliest bloomers are about wiped out. We have hardly any Paulareds.”

Honeycrisp, which is medium to late in blooming, “took it on the chin this year,” he said. But there are other factors. “We had a big crop last year, and they like to be biennial. If we hadn’t overproduced last year, they may have done better this year.”

It would be really useful to have some tool to hold back bloom, he said.

“I’m surprised we got as far as we did,” he said. “We had crop persisting through all the April freezes, right up to April 29.”

Undertree irrigation helped. “There’s more fruit showing up there,” he said.

He also believes that tree health made a difference. He’s not sure how it works, but trees that have adequate amounts of nutrients, especially the micronutrient zinc, seem to have healthier buds that are more resistant to freeze damage. “Where we can gain a degree or two, it helps,” he said.

With a quarter crop, Mike was maintaining all the trees the same as he normally would. After the second-generation codling moth sprays are done, he’ll evaluate the crop again and decide whether to maintain a full pest-control program.

Ohio grower

Eshleman Fruit Farm on the south side of Lake Erie in Clyde, Ohio, shared the misfortune of fruit growers in a broad swath across the Great Lakes region. Richard Eshleman has about a quarter of an apple crop.

“It’s amazing how the peaches survived,” he said, noting that most of his fruit was okay until the last weekend of April. “That was a killer for us,” he said. Sweet and tart cherries were nearly all lost.

He noticed, too, that fruit survived better on north-facing slopes, where bloom was somewhat later.

Lessons

The freezes that struck across the upper Midwest, Michigan, Ontario, and New York in April came with cold, dry winds that make it difficult to protect against, but the events provided lessons for growers that may be useful in the future.

Michigan State University Extension fruit educator Phil Schwallier, who works with fruit growers on Fruit Ridge and the Belding area of west central Michigan, said it was learning experience, if not a pleasant one.

“First, we learned that wind machines do work, some better than others,” he said. “They didn’t cover the acreage we thought they would. Growers thought one machine would cover ten acres, but with this very cold, drying freeze, one machine protected only one, three, maybe four acres.”

Some growers used them repeatedly. “That seemed to save some flowers so we have some fruit,” Schwallier said. But there was not much atmospheric heat to be found and very little high-level warm air to be pulled into the orchard.

“We learned that healthier trees had more crop survive,” Schwallier said. “Fruit on stressed or weak trees succumbed, but with good fertility and good management, fruit survived much better.”

Undertree irrigation provided some freeze protection, he said, and orchards that were protected from wind—those near woodlots or buildings—fared better. “We see fruit in the first two or three rows under those conditions,” he said.

He’s not sure what provided the protection, whether it was that flowers where wind was blocked were less freeze-dried by the wind, or whether these rows retained residual heat without the blowing wind.

Better sites have slightly better crops, but air drainage doesn’t appear to be a huge benefit with strong, cold winds.

While south slopes are normally preferred for their sunny exposure, apples on north slopes bloomed slightly later, and some of them have fruit. Varieties also made a difference. Gala, Golden Delicious, and Rome all bloom later, and these trees have some apples, Schwallier said.

Schwallier and his MSU Extension colleague Amy Irish-Brown collected a lot of weather data in March and April that should be useful to growers in the Fruit Ridge and Belding area.

Deborah Breth, an extension fruit educator in western New York, doesn’t think growers will learn much more from this year than they would have from reading their textbooks. Few growers have the kind of temperature records that it would take to gather site-by-site data.

They’ll see happening much of what the textbooks would have predicted:

Some varieties are worse off than others depending on their bloom date and stage of development. Terminal tip bearers should fare better than spur types. Varieties like Gala that bear some fruit on year-old wood, and bloom later, will have partial crops.

Quality of the fruit may provide some valuable lessons later. Will customers who want to buy their apples locally be willing to accept fruit that is russetted, or lopsided, or has frost rings?

Leave A Comment