As if the world needed another 2020 curveball, along came the eccentric Northwest sweet cherry season.

Of course, the coronavirus pandemic lurked behind all of it, skewing shoppers’ habits, but in the end stay-home orders seemed to boost demand after marketing experts spent the spring concerned about the opposite.

“It’s just another year in the cherry business because they’re never the same,” said B.J. Thurlby, president of the Northwest Cherry Growers, the Yakima, Washington, organization that collectively markets fruit from Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Montana and Utah. “But I would call this a monumental year.”

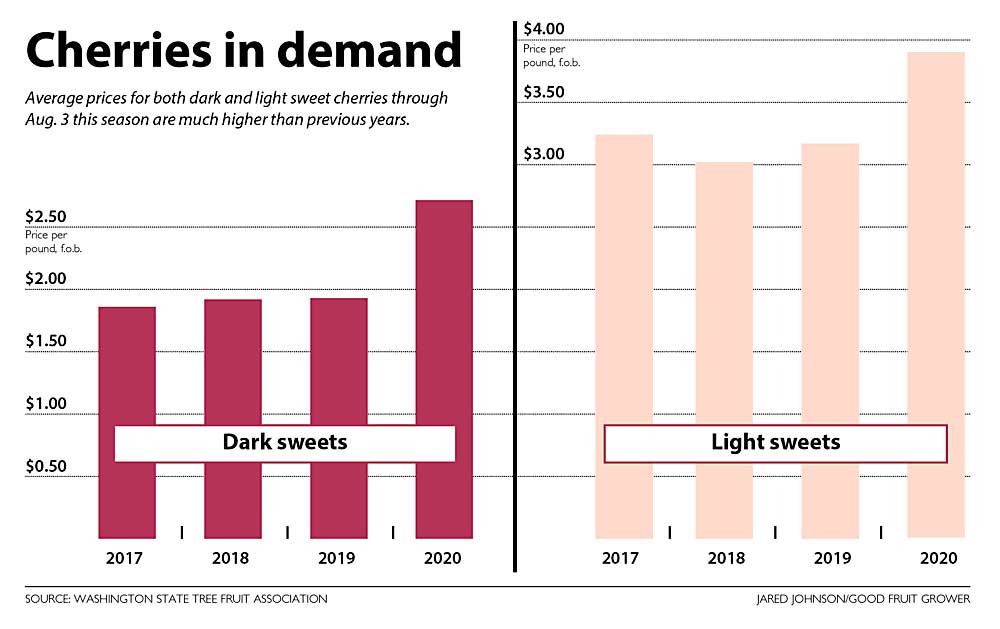

On the good-news side of the equation, prices stayed high all season, with average f.o.b. prices for dark and blush varieties through late July about 40 percent higher than the previous three-year average.

Mac Riggan, marketing director for Chelan Fresh of Washington, called the marketing season “perfection.”

“Man, cherries are selling like crazy,” Riggan said.

Typically, prices start high with the first shipments and decline as the seasonal excitement wears off. This year, prices stayed above $2.50 per pound through July. For example, on July 16, the average f.o.b for dark sweet cherries was $2.68, 56 percent higher than the average of the previous three years from the same date.

Riggan suspects there’s a lesson this year. Maybe, he said, prices can stay high in years to come and find a new normal, to borrow an overused pandemic phrase. For many years, decades ago, cherries sold for 99 cents per pound as a rule. “I think that new 99 cents could be $2.49, $2.99 going forward,” he said.

High demand also led to frustration for sales representatives, who at times struggled to fill orders. That differed from the spring when marketing executives viewed the upcoming season with both optimism and “trepidation,” Thurlby said. Statistics routinely show that fresh cherries rely heavily on impulse purchases in-store, but a marked increase in online shopping meant people were visiting stores less frequently.

Graphic: Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower)

Once the season started, however, shoppers still picked up cherries, either through online orders or in prepackaged bags from displays as they hastily made their way through the store. Advertising and publicity about the health benefits of cherries may have clicked with shoppers suddenly facing health concerns, Thurlby said.

The cherry industry, which doesn’t have the budget to compete against large food companies in advertising, relies on retailers themselves to display cherries prominently in stores and scrambled this year to convince retailers to do the same online. Walmart took the effort a step further this year, passing out free sample bags of Northwest cherries with curbside pickup.

“For the first time, a perfect storm worked for them (growers), not against them,” Thurlby said.

Sporadic volume

Thurlby expected the 2020 cherry crop to top out at nearly 200,000 tons, the lowest volume since 2015. Tree removals, driven by little cherry disease, caused between 25,000 and 30,000 tons of that drop, while a hard cold snap in mid-April, a total of six rain events and some wind, accounted for the rest.

Like every year, problems were scattershot. Rains picked on some orchards but left neighbors untouched. Frost hit some elevations but not others maybe 50 feet higher. Some blocks were so thin, growers didn’t bother picking. Other producers reported an average of half crops across the board. Still others gushed about record volumes.

Drew Myers of Seattle owns cherry orchards near Benton City and Chelan, Washington. The 55-acre Benton City blocks with early varieties, such as Chelan, Rainier and Bing, were a total loss from frost and rain.

The 15-acre block of Sweethearts at his Haspa Hill Fruit Growers orchard north of Chelan produced at roughly half the usual 8 tons per acre.

“The fruit was as beautiful as we’ve ever seen, it was just low tonnage,” he said.

However, he’s optimistic about prices turning into high returns from his packer, Chelan Fruit. “I’m excited about the prospect of breaking even for once,” he said.

Matt Jeffery of McDougall and Sons, a Wenatchee production company with plots throughout Central Washington, said yields varied location by location, though they averaged under half of normal. Orchards in Monitor and Ephrata didn’t pick at all, while others produced 12 tons or 14 tons per acre.

“Despite the good prices, it’s still a break-even year,” Jeffery said.

Erik Olson of Selah, Washington, harvested his largest crop ever, in spite of severe cold spells in mid-April that had him working around the clock with irrigation, wind machines and smudge pots.

“It was two of the hardest nights I’ve ever spent in my life,” he said.

It paid off, he said. He averaged 6.5 tons per acre, even with about 20 percent of his trees still shy of full production maturity. Meanwhile, his packouts were high with mostly 9-row and 9.5-row sizes, and he cautiously hopes the high prices he has been reading about translate into high returns.

“It was a farmer’s dream,” he said. •

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment