A Washington State University researcher believes growers do not have to wait until postharvest to find out if their fruit is infected by postharvest pathogens.

Achour Amiri is developing a way to detect key pathogens in the orchard, while apples and pears still hang on the tree, with a test that yields results in less than an hour — without sending samples off to a full laboratory.

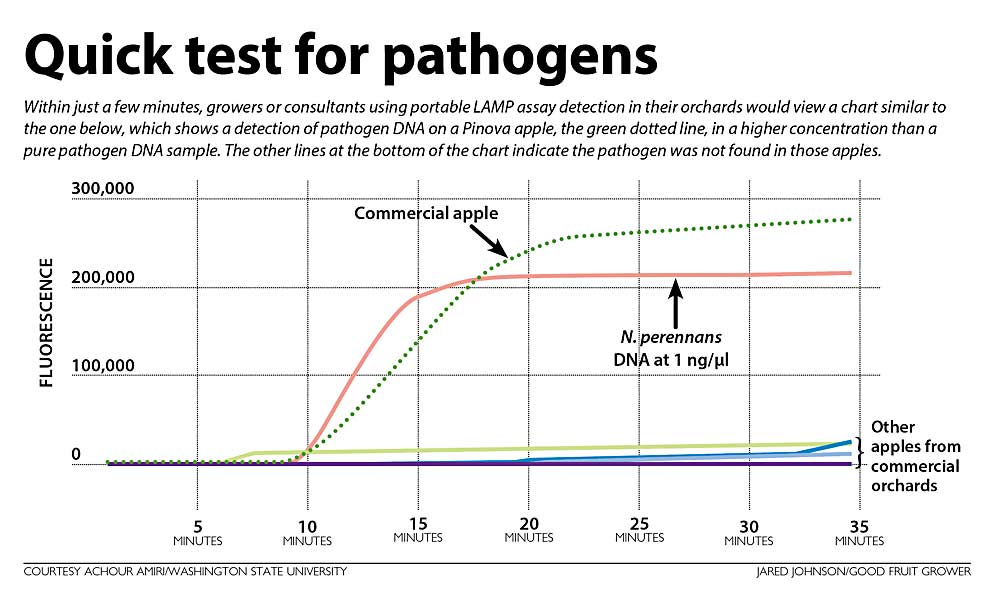

Amiri, a plant pathologist at WSU’s Tree Fruit Research and Extension Center in Wenatchee, believes growers or consultants can use portable LAMP assays themselves in their orchards as early as bloom — leaving plenty of time to take corrective measures — to detect any pathogen, once researchers develop a set of DNA primers for each one. He plans to hold a workshop in March, pandemic permitting, to train growers and others to use the technique.

“It’s useful for both growers and the packer,” Amiri said.

Meanwhile, a researcher at Cornell University in New York developed a similar tool to detect fire blight before visual symptoms show up.

LAMP

LAMP, shorthand for loop-mediated isothermal amplification, is a method of amplifying DNA — a critical step in genetically diagnosing diseases — more quickly and more nimbly than traditional PCR. That approach, the polymerase chain reaction, requires expensive laboratory equipment.

LAMP technology was first developed around 2000. Medical professionals use the assays to diagnose human diseases in clinics without full-scale laboratories. Some researchers have proposed employing LAMP to quickly diagnose COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus. Portable LAMP machines cost anywhere from $4,000 to $18,000 and take up about as much room in a pickup as a lunchbox.

However, they only can detect the organism they seek. Amiri’s breakthrough came when he developed a set of primers — reagents carried in liquid form — that allow the LAMP machine to detect a species of Neofabraea, the pathogens that cause bull’s-eye rot.

During his three-year, $55,000 project funded by the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission, Amiri used a portable LAMP machine, called the Genie II, to detect naturally occurring Neofabraea on Golden Delicious and Pinova apples 90 days before harvest. Both cultivars are especially sensitive to bull’s-eye rot.

He also is nearing completion on a set of primers for Phacidiopycnis washingtonensis, the fungal pathogen that causes speck rot in applesand a related pathogen, Phacidiopycnis pyri, that causes Phacidiopycnis rot on pears.

All are threats to the fruit industry. Bull’s-eye rot, an export quarantine problem, accounts for between 8 percent and 10 percent of decayed storage fruit, according to surveys by Amiri in 2016. It causes depressed, circular lesions originating from the lenticels. Speck rot, which causes a water-soaked appearance that turns brown or black with time, accounts for 15 percent of postharvest decay in apples and 20 percent in pears. Both can be managed with preharvest fungicides. (For more information, visit http://treefruit.wsu.edu/post-harvest-diseases/.)

In his trials, Amiri’s LAMP assays were sensitive enough to detect as low as 0.001 nanograms of DNA on Golden Delicious apples, a particularly sensitive variety, artificially inoculated with N. perennans at the Sunrise Research Orchard east of Wenatchee.

Industry benefit

Early detection can let growers take earlier and more precise action, said Sam Godwin, an apple grower in Tonasket, Washington, and a research commissioner.

“Having tools to know where things are at and what’s going on is always better than having to guess and react after the fact,” he said.

Meanwhile, bull’s-eye rot is more common than many growers realize, said Harold Schell, a research commissioner and a horticulturist with Chelan Fruit Cooperative. Prevailing belief long held that the disease affected only 50-year-old Golden Delicious trees with perennial cankers.

“That attitude or idea is no longer valid,” said Schell.

Research commissioner Jeff Cleveringa sees application for warehouses, too. Bull’s-eye rot is a quarantine disease for many countries. A rapid test to diagnose it in an American warehouse would save time and money before it leaves port. Even a small amount can spread en route to foreign harbors.

“In a 30-day boat ride to Asia, you could have an explosion on your hands,” said Cleveringa, head of research and development for Starr Ranch Growers. •

—by Ross Courtney

Method can help find fire blight

While a Washington State University researcher develops primers to enable rapid field detection of fungal pathogens, Awais Khan of Cornell AgriTech at Cornell University has used a similar approach for fire blight detection.

Khan developed tools for rapid and sensitive detection of the dreaded bacterial disorder and has begun training growers, consultants and extension specialists on how to use immunostrip kits and LAMP assays to diagnose fire blight before visual symptoms appear, or to distinguish the pathogen from other disorders that may look similar to even well-trained eyes. The methods he has evaluated are available commercially, though few have adopted them yet, Khan said.

The immunostrips rely on antibodies to confirm the presence of the pathogen’s proteins, much the way a pregnancy test works. In his research, Khan used two different commercial kits.

He also developed primers that allow LAMP assays to detect the fire blight bacteria DNA. Machines to run the LAMP assay, used in the medical field and for disease diagnosis in crops such as tomatoes, citrus and grapes, run between $4,000 and $18,000 and are about the size of a lunchbox.

Both the LAMP and immunostrip tests yield results in an hour or less.

So far, his work has been in New York, but he is looking for collaborators on the West Coast to try his fire blight detection methods.

The LAMP assays are more sensitive than immunostrips but are also more expensive. Running them requires some technical expertise, while the immunostrips are simple enough for every grower to carry. LAMP technology would make more sense for managers of large orchards, crop consultants, extension specialists or diagnostic labs, Khan said.

Still, they can benefit all growers. In the East, problems such as spray damage or Nectria twig blight often look similar to fire blight, even to experienced horticulturists, he said. A small misdiagnosed problem could get a lot bigger in a hurry.

“That will be the end of the orchard,” he said.

—R. Courtney

Fantastic..work..

Please connect me to Entomologist

Myself Dr Jagdish, Scientist Entomolgy ICRISAT, India

Email : j.jagdish@cgiar.org