Back in the 1980s, it was not uncommon to find bundles of old apple box labels lying around in fruit warehouses in Washington State.

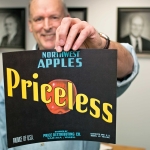

“We had some in our old packing room, and I didn’t think much about it,” recalls Bob Price, president of Price Cold Storage and Packing Company in Yakima.

But then it occurred to him that maybe he should start collecting them.

Characteristically, Price decided that if he was going to do it, he would do it right. Label collecting became his passion and, over the past 30 years, he has amassed thousands of apple labels to form one the largest collections in the country.

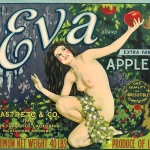

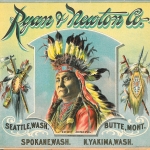

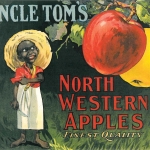

Washington apple labels date back to the turn of the 20th century when the industry was in its infancy. Apples were packed in wooden boxes with colorful lithographed labels of the brands glued on the sides.

The oldest labels are from the Opportunity area near Spokane, where apples were grown before orchards were developed in central Washington, Price said. He has old Perham Fruit Company and Earl Fruit Company labels with Spokane printed on them. There were also orchards in the Hanford area before it became a nuclear reservation.

Apple labels were used until the 1950s when wooden bins were introduced for harvesting apples and packers transitioned to cartons. The transition for pears came later, in the 1960s.

Price says there are far fewer apple labels in the eastern United States than in the West because fruit there used to be picked and shipped in baskets without labels.

Treasure hunt

During the 1980s, numerous Washington packing houses closed or changed hands as the industry consolidated. Price recalls visiting old warehouses and stumbling across bundles of labels that people were sometimes happy to give away. It was like a treasure hunt. He found Washington Fruit and Produce Company labels glued to a horse barn.

At first, he focused on collecting Yakima apple labels, which had a special significance to him because he knew the fruit growing and packing families whose brands were on the labels.

“My joy in doing this initially was I knew a lot of people who were no longer in the fruit business, so I would make a copy of the label and have it framed and give it to them for Christmas,” he said.

As he got more serious about collecting, he would trade with other label collectors around the country. He expanded his interest to pears and other geographic areas. He has a couple of hundred apple labels from Australia and one from Cuba. He’s been less interested in California labels just because there are so many of them, particularly for soft fruits and citrus.

Over the years, several major collections have been broken apart and sold, and he acquired some labels that way.

“There are fewer collectors out there now,” he said. “In the late nineties it became where most of the label traders were like horse thieves. They’d find something and say there were only two or three in existence when there would be a whole bundle of them, so I quit trading labels.”

Yard sale

He still keeps his eyes and ears open, though, and occasionally goes to major swap meets and checks online. The most he’s ever paid for a label is $500. He’s never sold one.

Some labels, possibly stored in someone’s basement for many decades, show up unexpectedly. A couple of years ago he had a call from a person who had bought a box full of items at a yard sale. When the man unpacked the box, he found the bottom was cracked and had been lined with a fruit label to stop things from falling through. He contacted Price and it turned out to be a label he didn’t have.

Another label, which Price had never seen before, was found in the basement of a Congdon Orchards packing room.

“It had gone through the cracks in the wooden floor into the basement and was sitting in the dirt, and no one had seen it,” Price said. “It’s weird how you find stuff.”

Such a serendipitous find has Price feeling like a kid in a candy store, he said. “In my position when you find something you didn’t have, it’s kind of fun. If I get two to three labels a year that I don’t have, it’s pretty amazing.”

Value

Price says his collection of thousands of labels is undoubtedly worth a lot, but his intention was never to build a collection to sell.

“I’m not sure someone would pay the full amount that it’s probably worth,” he said. “It would be piecemealed out, and what do you do with the rest?”

He has a couple of dozen labels that are the only ones known to be in existence.

“What kind of value do you put on that?” he asked. “If there’s only one left, is it worth $1,000? Is it worth $10,000? What is it worth?”

Organizing

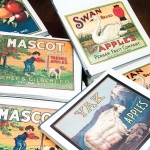

Nowadays, Price is focusing less on collecting and more on documenting, scanning, and organizing his labels. They’re filed in special display books categorized by the name of the producer. He keeps copies of labels he knows of but doesn’t yet own, with the idea of substituting a real one when he finds it.

Many labels differ only slightly. Typically, a label design would be reproduced with three different background colors to denote the different grades of fruit. Some of the text might differ because of changing standards over the years, so there might be almost identical labels but with different weights indicated, such as 40 pounds net, a bushel, or not less than 42 pounds.

He has all known Price Cold Storage labels except one, and he has a copy of that. One of their brands was Priceless.

Some of his copies are from the Yakima Valley Museum, which has the world’s largest collection of Yakima fruit labels. Others are from the Smithsonian Museum’s collection of 300 to 400 apple labels that were donated by the family of a New York City collector.

Price is a trustee of the U.S. Apple Association and has visited the Smithsonian three times while in Washington, D.C., for meetings.

He had to make appointments in advance, and museum staffers watched over him as he looked through the labels. Though modest in scope, the Smithsonian collection includes some unusual Yakima labels that even the Yakima Valley Museum lacks and that possibly no one else in the world has. Price was able to obtain digital images of those.

He has also been talking to Smithsonian staff about perhaps donating his far larger collection to them some day so that it can be on public display. For example, he has 400 different labels of Skookum alone.

Price says his two children are not involved in the fruit industry and probably not interested in maintaining the collection.

Son Tyler recently graduated from Stanford University with a master’s degree in business administration and works for Apple in California. Daughter Jamie works for Morgan Stanley in Bellevue, Washington.

“They’re in their late twenties, and their goal is not to sit around and work on a collection of anything,” he said. •

just curious, anyone have any idea what should I do with my crate label collections that my children/ family do not want?

I would like to donate them to someone who will appreciate them as much as I do. I’m not trying to get the money spent back, I really don’t want them ending up at a goodwill

-I have 49 of 50 Unites States

-flowers, some quite rare: willow tree & morning glory

-blue goose collection: different states, fruits & vegetables

any ideas?

thanks

Barbara

(someone who is obsessed the beauty of crate labels)

I am the curator at the yakima museum as well as a collector. I can find a good home for them