Most Chilean sweet cherries are sold in export markets, which means their quality has to be high.

Growers in the Pacific Northwest are curious about the growing methods used by the South American country to ensure that quality crop, including the use of plastic covers, said Bernardita Sallato, a regional tree fruit extension specialist with Washington State University who studied horticulture in Chile.

Plastic covers and high tunnels are not used extensively for rain protection in Washington, where fruit is mostly grown in dry regions. However, a changing climate and a greater number of rain events during the last few harvests have Washington growers considering the benefits and costs of using plastic covers, Sallato said.

“Rain can completely destroy your crop if you have a susceptible variety without protection,” she said.

To provide Pacific Northwest growers more information about the use of plastic covers in Chile, Sallato arranged to have Marlene Ayala, a fruit researcher with the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, give a presentation during the Cherry Fruit School last March. The Cherry Fruit School is organized by WSU and Oregon State University.

According to Ayala, growers in Chile’s key cherry region, the Central Valley, use plastic covers to protect sweet cherries from frost, rain and hail. Ayala and other Chilean researchers are examining the risks and benefits of covers and tunnels in the Central Valley, as well as in other regions where weather can pose even greater challenges.

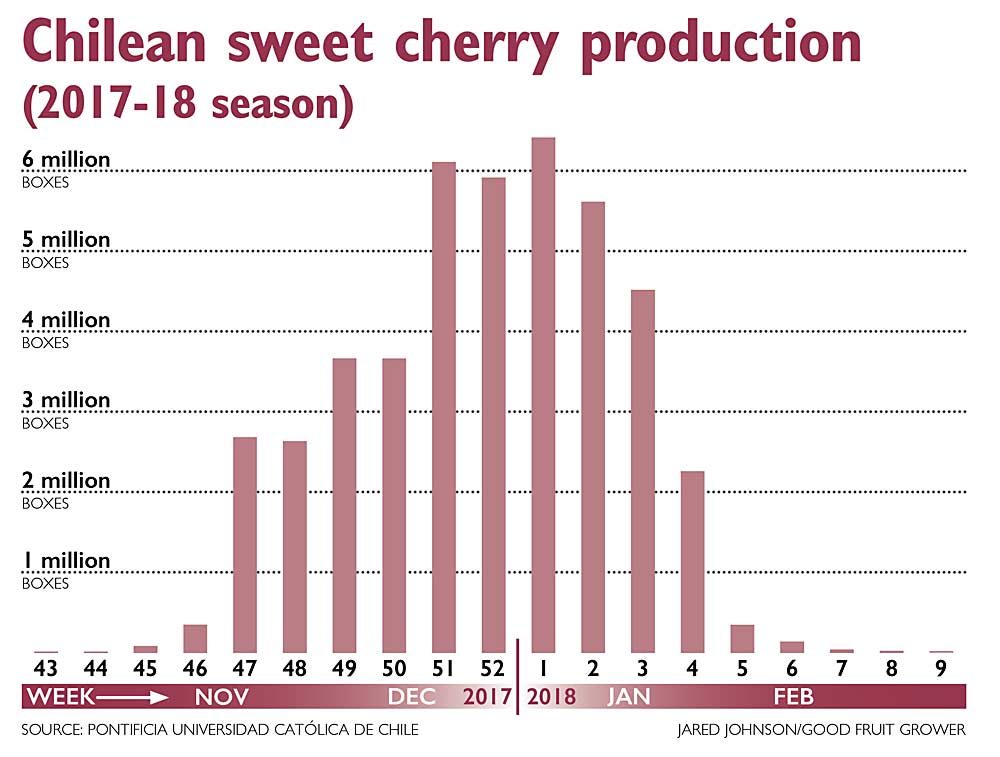

Sweet cherries are a growing business in Chile. About 30,000 hectares (roughly 74,000 acres) of cherries are in commercial production, and commercial plantings are increasing by 7 percent each year. Business is so good that nurseries are running out of plants, Ayala said.

Most of Chile’s sweet cherry production, roughly 90 percent planted in early- to midseason varieties, sits in the Central Valley. Growers are increasingly planting later varieties further south, however, thanks to cheaper land prices, available water and warmer temperatures due to a changing climate.

The country’s growers have transitioned from traditional orchards of 200 trees per acre to higher density, precocious trees planted at 330 to 450 trees per acre. In the past eight years, newly bred varieties have been planted at 600 trees per acre, Ayala said.

Cherries can bring good returns for Chile’s medium- and large-sized growers, if they can avoid frost or weather-related problems. Rain isn’t a huge problem in the Central Valley, though if it arrives in the spring, between September and December, it can cause bud damage, flower damage and fruit cracking. Rainfall can pose greater challenges for growers to the south, she said.

Some 6,200 acres of Chile’s sweet cherries are now covered by plastic covers or tunnels. To study their impact, Ayala conducted two research trials in the Central Valley during the 2017–18 growing season: One trial compared high tunnels versus uncovered fruit, while the other compared high tunnels to three-wire systems and uncovered fruit.

Chilean cherry growers have less experience with tunnels than with three-wire plastic covers, or tents. In the Central Valley, tents are mostly used to protect cherries from cracking and frost. They’ve also been shown to prevent hail damage. High tunnels have mostly been used to advance the blueberry harvest, Ayala said.

Her first research trial was held in the Central Valley’s Curicó region. It compared high tunnels versus uncovered cherries in blocks of the Royal Dawn variety on MaxMa 14 rootstock. Among its findings:

—Covered trees bloomed five days earlier than uncovered trees, and their harvest date was eight days earlier, because of the greater heat that accumulated inside the tunnel. “So, the high tunnels speed up harvest and bloom,” Ayala said. “That was very important for us. In November, that is a huge difference in price.”

—Soil water content was more stable under the tunnel. There wasn’t much cracking during the rain events, compared to the uncovered.

—Fruit under the high tunnel was 10 percent larger, but softer and with less soluble sugar content, according to Ayala.

The second research trial also was held in the Curicó region. It compared high tunnels, three-wire systems and uncovered cherries in orchards of the Santina variety on Colt rootstock. Among its findings:

—High tunnel cherries were harvested 10 days before uncovered cherries; tent cherries five days before.

—High tunnels had larger fruit compared to the tent and uncovered trees.

—Fruit under the covers was softer than on the uncovered trees, particularly at the tops of the trees, according to Ayala. “We know that on covered trees, the fruit is softer, but we wanted to confirm it. And it happened,” she said.

Being able to advance, or delay, harvest could be beneficial for Washington growers, helping them take advantage of more profitable harvest windows. Reduced firmness is a problem, however, since firmness is one of the main parameters of fruit quality, Sallato said.

The use of plastic covers in Washington might grow, but Sallato doesn’t expect it to be widespread. At least, not yet. The cost is high, and Washington growers don’t get the same returns as Chilean growers, she said.

“In Chile, it makes more sense to use covers,” Sallato said. “They can afford it. They get better prices for their cherries.”

In October, Ayala was still studying plastic covers, mainly high tunnels. For the 2019–20 season, she planned to work with another researcher to evaluate the reduced use of irrigation water under tunnels. She said water demand is lower under tunnels, by about 20 percent compared to uncovered trees. They’re studying how that 20 percent reduction affects fruit quality and postharvest life.

“This is important to make more efficient water management, particularly during this year, when we have a strong water restriction due to global warming in Chile,” Ayala said. •

—by Matt Milkovich and Shannon Dininny

[…] It is worth mentioning that the Central Valley of Chile is the area with the highest production of sweet cherries in the country, which has experienced a remarkable growth in its production in recent years. Therefore, Marlene Ayala, a researcher specialized in fruit trees, decided to perform 2 studies on the crops of the region that are reviewed in the journal Good Fruit Grower: […]