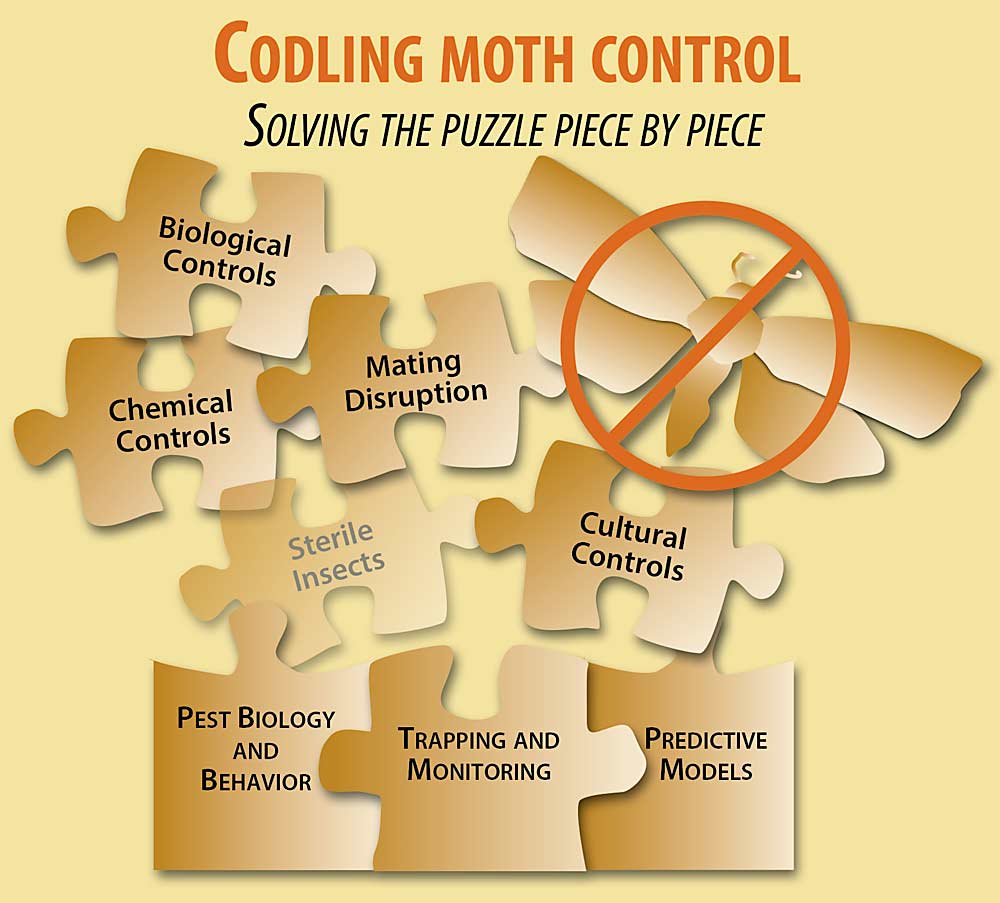

Successful codling moth control results from growers and pest consultants putting together many pieces. The leaders of a recently formed codling moth task force believe that understanding this big picture of how different aspects of the codling moth program fit together and influence each other is critical to successful IPM programs.

Some pieces, such as understanding pest biology and monitoring to assess pest pressure in individual orchards, provide the foundation upon which the rest of the control is built.

As Good Fruit Grower rolls out more coverage of the Codling Moth Summit and other stories on this topic, we hope using this piece-of-the-puzzle framework helps to show our readers how it’s all connected.

Washington apple producers have enjoyed a long run of stable, integrated pest management resulting in relative control of the crop’s key pest — codling moth — and enabling the rebound of many natural enemies that control secondary pests.

But growers today “can’t take that success we’ve had in the past for granted,” said Mike Doerr, an account manager for Wilbur-Ellis and member of the codling moth task force established last year to support and maintain that success.

“The development of our IPM programs has been regarded as one of the great successes in agriculture,” Doerr said. “But no matter how successful we have been in the past, it’s imperative we keep that information relevant under today’s conditions.”

Today’s conditions are more complex than ever: more organics, more selective pesticides, more options for traps and lures and pheromone dispensers. No one-size-fits-all recipe applies when it comes to designing a program, said Byron Phillips and Rob Curtiss when they spoke at the virtual Codling Moth Summit in February.

“I view IPM as a data-driven strategy but with site-specific tactics,” said Phillips, a key account manager at Wilbur-Ellis. Building a program starts with understanding temperature-driven development, beginning with setting biofix (the first flight of codling moths in spring) using both WSU’s models and trapping at every site to record the first catch.

Take this spring for example: WSU predicts biofix at 175 codling moth degree-days, but he saw the first trap catch of 2022 in southeast Washington, in Wallula, on April 23 at 206 degree-days, a full 15 days after the 175 was recorded.

This followed a mid-April cold snap with snow, rain and wind.

It’s an “interesting illustration of the influence of cold weather on both biology and behavior,” he said in a follow-up interview.

When it comes to trapping, Phillips said he sees too many growers placing traps only at corners, for convenience, but this approach can be misleading. He recommends the triangular delta traps at a rate of one trap per 5 acres.

“I would bet our industry average is closer to one trap for 15 or 20 acres, and I think that gets us into trouble sometimes,” he said.

Both Phillips and Curtiss mentioned that the proliferation of lure options can make it hard to understand how trap catch relates to pressure throughout the season. (And using sterile insect release can result in trap flooding.) Phillips also said he likes to use some 1X lures to tell him if he has any gaps in his mating disruption.

“I’m a firm believer that the more point sources you have, the more effective mating disruption,” he said, citing 400 per acre as a target. Only in large blocks with low pressure will he consider switching to aerosols to save labor, and he keeps the 400 hand dispenser rate along the borders.

Phillips said insecticides are needed to set up mating disruption for success, not to be the primary control tactic. Cultural control tactics (See “Control culture club”) also play a role in keeping pressure low. That hasn’t changed since the advent of mating disruption, but the chemistries have.

Organophosphates “were effective on all life stages, so timing wasn’t as critical,” he said. Now, growers must consider the off-target effects on natural enemies that help to keep secondary pests in check.

“One thing that bugs me … is the overuse, or for me, any use of Lambda-cy,” Phillips said. “It’s so extraordinarily disruptive of IPM. I cringe when I see how much we are using.”

Growers and their pest consultants also need to factor in the economic profile of each orchard block, he said. Tactic costs range from $85 an acre to $1,500 an acre, and growers have different levels of resources. “This helps me to optimize the use of available tactics,” he said.

Curtiss talked about the structure of a spray program, which starts with a residual ovicide well before biofix. That dormant spray offers the best chance to kill the most eggs with a single pass, said Curtiss, a postdoctoral researcher at Washington State University’s Tree Fruit Research and Extension Center in Wenatchee. Then, it’s on to larvicides.

“Due to the short time a larva is exposed, ideally you’d use a fast-acting product,” he said, rotating modes of action to prevent the development of pesticide resistance.

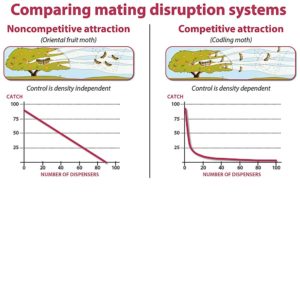

These early-season control tactics are critical to IPM, Curtiss said, because mating disruption is a numbers game.

“Codling moth mating disruption cannot control high populations,” he said. “It needs to be integrated with other control strategies. And mating disruption helps to maintain effectiveness of current insecticides.”

Of course, a spray program is only as good as your sprayer’s calibration and operation. One of the most common mistakes is spraying too fast, Phillips said.

“Everything is important, but the single most important thing I see growers doing (that) they could change to improve codling moth control is slowing down,” he said. •

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment