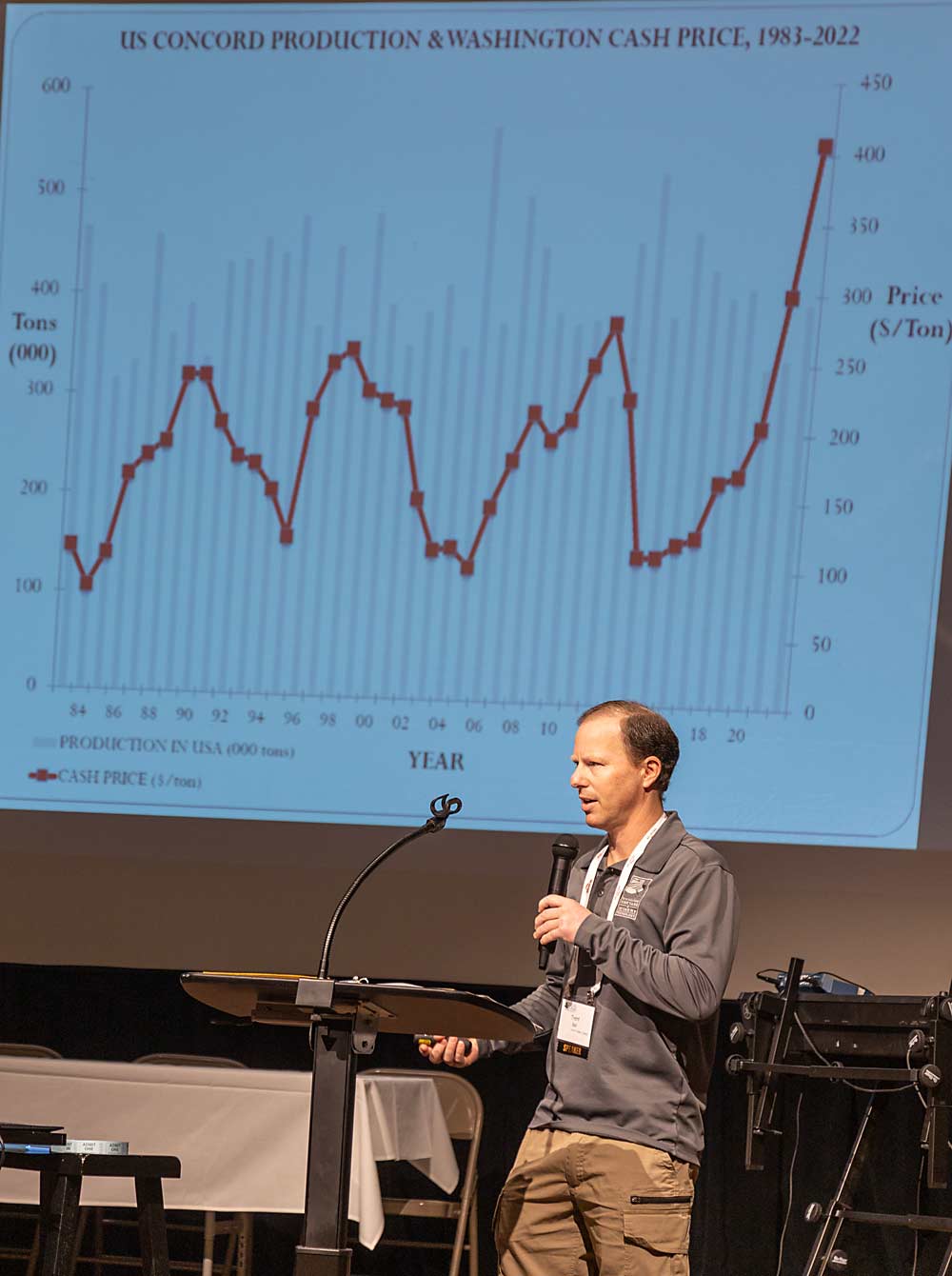

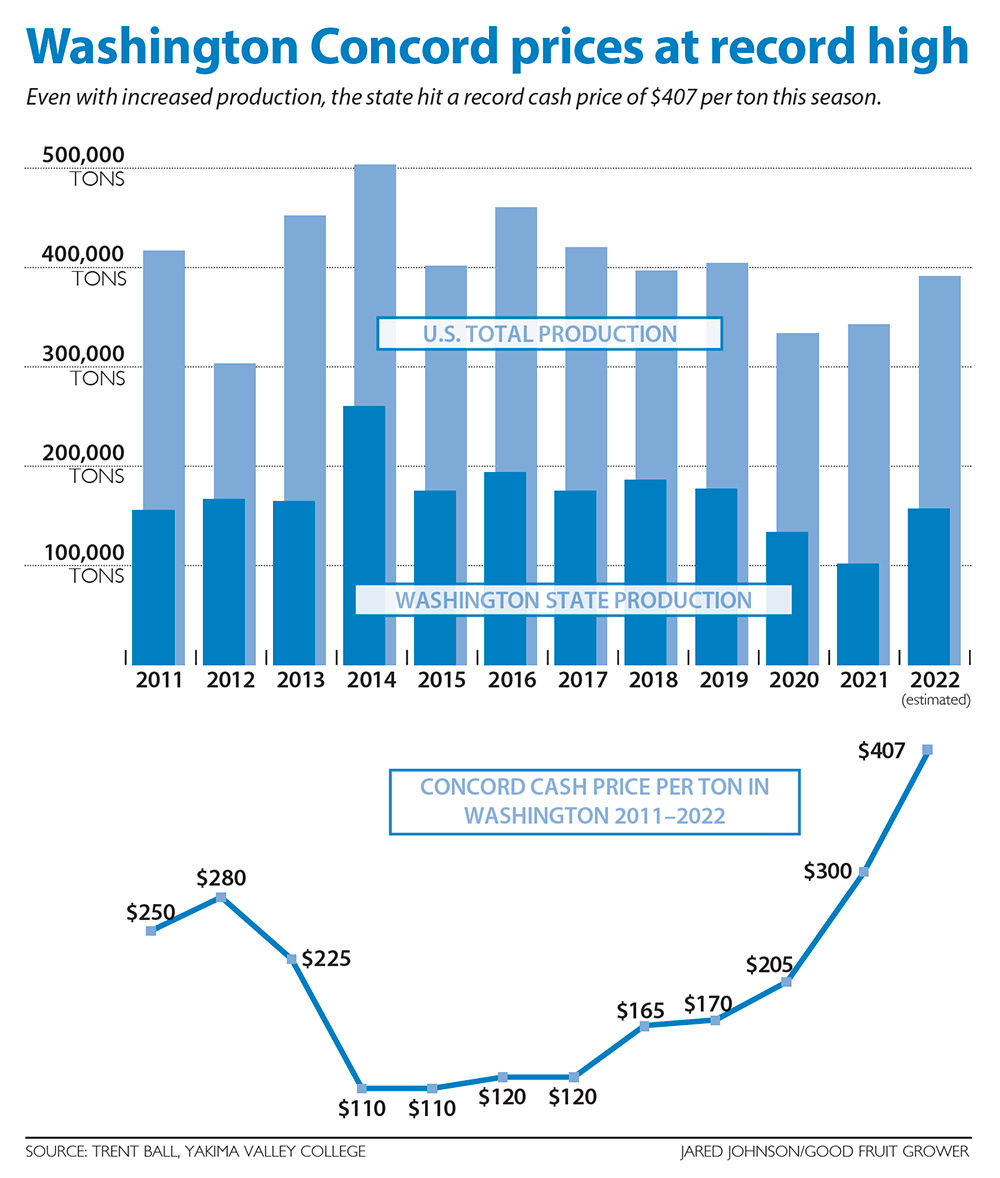

Washington’s Concord production rebounded in 2021, but prices continued to rise, hitting a record cash price of $407 dollars per ton in 2022.

“For several consecutive years, we’ve had inventories pretty low going into the harvest season, which is a big driver of what we are seeing with regards to the cash price,” said Trent Ball, director of the vineyard and winery technology program at Yakima Valley College, during his annual economic update at the Washington State Grape Society meeting in November. “There’s been a perpetual increase going on and then a big jump this year, which was fantastic.”

Beyond the off-the-charts pricing, the outlook is good for the Washington industry, Ball said.

2022 experienced a late growing season following the “winter that came back again in April,” as Ball said, with harvest starting about three weeks late and some growers scrambling to finish in November. Still, sugars were good, although down from the heat-concentrated, low-yield crop of 2021. Growers harvested 157,000 tons from just shy of 16,000 acres in 2022, with average yields of 9.9 tons per acre.

In the Eastern U.S., Michigan had its largest crop since 2016, and the New York and Pennsylvania growing region harvested about 190,000 tons — spot-on with the 10-year average. That region is now likely to outproduce Washington going forward, Ball said.

The Eastern cash price was $375 per ton, up from $325 in 2021, although most growers were receiving higher contract pricing from National Grape, the cooperative behind the Welch’s brand.

“It’s not very often that you see the Washington price above the Eastern price, but it did happen in 2022,” Ball said. He expects that, if current conditions continue, prices in the East will catch up in 2023.

So, what’s driving those increases? Acreage in Washington has come down steadily since 2014, when prices fell to $110 per ton amid oversupply and as the U.S. crop exceeded 500,000 tons.

The 2022 U.S. crop was estimated at 391,000 tons. Ball sees 400,000 as the new ceiling, given all the vineyards growers have pulled out on both coasts.

“That plays a lot into what we’re seeing with the pricing that’s happening,” he said.

The concentrate price is also high — $20 per gallon in the Eastern market and $18 in Washington — which historically has been challenging for the Concord industry because processors will switch to lower-cost alternatives. This time, there are no inexpensive replacements available, Ball said.

Meanwhile, imports are on track to be at the lowest level in 25 years, due to weather and global trade challenges.

Given all that, Ball said the outlook is optimistic. The high 2022 crop sizes in each region mean production will likely be down a bit in 2023, and inventory remains low. Growers don’t appear to be replanting significantly, which portends more market stability rather than the cycle of ups and downs the Washington industry has experienced for 40 years.

“Hopefully, it’s going to stay steady,” Ball said. “Sales are strong, so we anticipate the cash price remains high. That will be some good news.”

Ball also touched on the outlook for wine grapes. During the pandemic, the industry took a pricing hit, as consumers drank lower-cost wines at home rather than spending in tasting rooms and restaurants, but volumes remained consistent and pricing rebounded in 2021, Ball said. In 2022, U.S. wine sales just surpassed 2021.

“It’s not a great amount of growth, but it is growth from where we were last year,” Ball said.

Washington growers were harvesting an unusually large crop in 2022, after being down from both heat and cold damage in the previous two vintages. But with the late-season harvest stretching into November for at least a few growers, Ball only had a preliminary estimate from the Washington Winegrowers Association to share, which put the crush at 310,000 tons.

That would be a record, surpassing the 260,000 ton-crop in 2018 and the 270,000-ton crop in 2016.

Growers in California estimated a harvest of around 3.5 million tons, after some frost issues reduced fruit set in some regions and August heat reduced yields in others, Ball said.

“It was a season filled with curveballs,” according to the 2022 harvest report from the Wine Institute, the California industry’s advocacy group, but the industry still expects a high-quality vintage.

—by Kate Prengaman

Grape Society recognizes a grower and a communicator for decades of sharing and supporting the industry

At its annual meeting in Grandview in November, the Washington State Grape Society gave its Lloyd H. Porter Grower of the Year award to Gary Schrimsher of Kennewick.

He was the longtime vineyard manager for Snake River Vineyards in Walla Walla, and, during the 1980s, industry representatives from around the country would visit to learn from Schrimsher about how he was achieving record-breaking yields, said Catherine Jones, president of the grape society. He also ran his own orchards.

Now retired, Schrimsher lives in Kennewick with his wife of 63 years, Peggy.

Schrimsher, who was quite surprised by the honor, told the audience that he was lured to the meeting by his brother-in-law. His time in the industry was “a very fun time,” he said. “We worked hard and we grew a lot of grapes, and I enjoyed all of the people I worked with.”

Today, farmers are facing a lot of challenges. “It’s really tough, I’m glad I’m retired,” Schrimsher said with a smile. “Thank you all for keeping up the fight and doing the good job that you are.”

Then, Washington State University viticulturist Michelle Moyer presented the Walter Clore Award recognizing service to the industry, honoring someone who “burns the candle at both ends with their work ethic,” and has “worked tirelessly for agricultural commodities for 35 years,”: Melissa Hansen of the Washington Wine Commission.

Hansen, the research director for the commission, was surprised with the award after sharing an update on the industry’s research efforts on smoke impacts, disease management and mechanization.

She previously covered the grape industry for Good Fruit Grower for 20 years and, before that, worked for the California table grape industry.

“This is really special because I’ve written about these award winners for many years,” Hansen said. In fact, her first article for Good Fruit Grower was an interview with Walter Clore about the early years of the Washington wine industry, so it’s a special honor, she said.

(You can read that article, a 1996 interview with the late Walter Clore, at bit.ly/hansen-clore-article)

—K. Prengaman

Leave A Comment