Climate change concerns from buyers and regulators are pushing agricultural commodity groups in new directions. Some have even started to participate in carbon-capture incentive programs such as carbon markets. But is there room for tree fruit in these programs?

People in the industry are trying to figure that out. At this point, it doesn’t look like it would make much economic sense for tree fruit growers to participate in carbon markets, which are designed to benefit the scale of larger commodity crops. But according to Good Fruit Grower interviews, the tree fruit industry still needs to stay abreast of climate-change-related developments.

“The first item on the agenda for the Biden administration folks has been climate change,” said U.S. Apple Association President Jim Bair. “It’s obvious that some kind of carbon capture program is going to be developed, and as I like to tell the officials in charge, the tree fruit industry is the original carbon-capturing industry. If farmers are going to be financially incentivized for capturing carbon, that has to include tree fruit growers.”

To give an overview of the situation, Bair tapped Bruce Knight to speak during USApple’s annual conference in August. Knight is the founder of consulting firm Strategic Conservation Solutions and has served previous presidential administrations at the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Knight said pressure to do something about climate change isn’t just coming from government sources. It’s also coming from large corporations, many of which buy agricultural products. It’s coming from young people who are just entering the workforce. The Biden administration, in fact, is unlikely to rely on regulatory action to pursue its climate goals and is more likely to rely on incentive programs. At this point, carbon markets are mostly voluntary and their rules are being set by the private sector, Knight said.

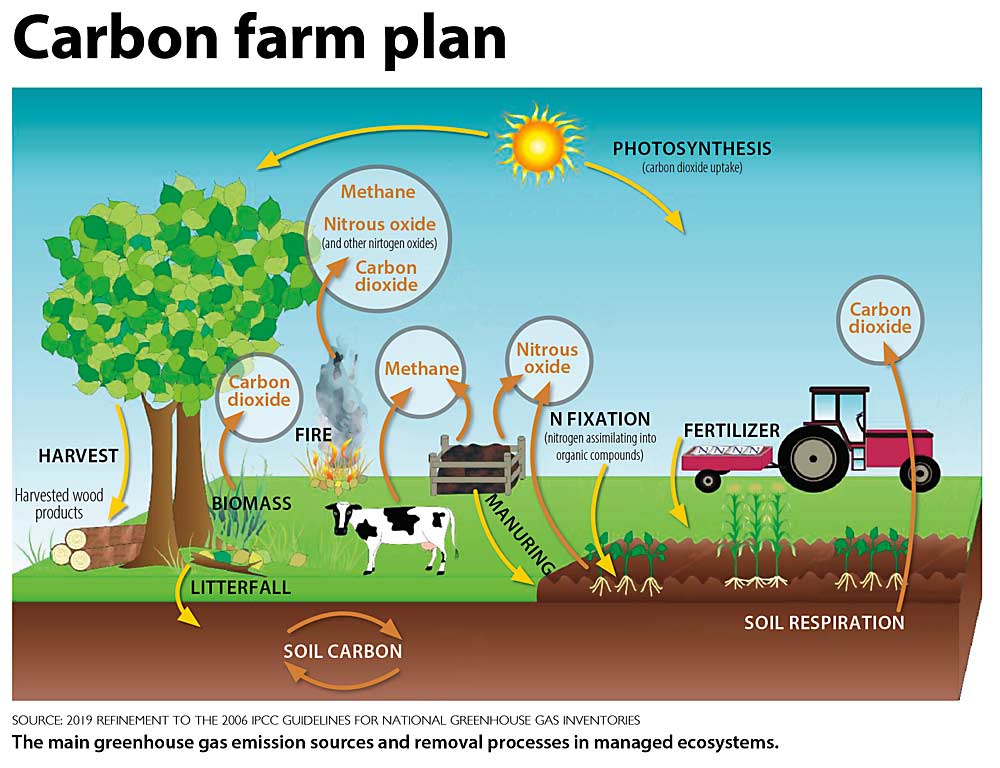

The rules and workings of carbon markets are still evolving, but Knight described the basic concept: If a company or government entity finds that it’s too difficult or expensive to reduce its own carbon emissions, it locates another entity — a farm, for example — that can lower its own emissions at a smaller cost and pays it a fee to do so. This “carbon credit” takes a similar amount of carbon out of the air in a more economically efficient way.

Emerging carbon markets, however, are designed for corn, soybeans and other commodity crops with their tens of millions of acres. Specialty crops are being overlooked, and the apple industry will have to take “decisive action” in order to be included, Knight said.

But does the apple industry — or other fruit industries, for that matter — want to be included?

The Northwest Horticultural Council has studied emerging carbon markets, and at present the tree fruit industry appears to lack the scale needed to interest the designers of private-sector markets, said NHC President Mark Powers.

Even if they were to participate, under current arrangements, apple growers might be paid $10 to $30 per acre for the carbon they sequester. Considering the “friction costs” associated with gaining access to carbon markets — paperwork, audits, compliance agreements — and the fact that growers invest tens of thousands of dollars in each acre of tree fruit, going to all that trouble to earn an extra $20 per acre doesn’t make a whole lot of economic sense, Powers said.

Tree fruit growers have a positive story to tell when it comes to carbon. Their trees automatically pull carbon out of the air and sequester it in the wood. Vegetation between tree rows increases the carbon content of soil. But it’s too early to say if those advantages can be monetized to an adequate degree, Powers said.

Even if carbon markets don’t make financial sense for tree fruit right now, growers can’t afford to ignore their carbon footprint. Sooner or later, their buyers are going to start asking questions. McDonald’s, for example, wants its supply chain to be “carbon neutral” within a couple of decades. That probably concerns potato growers and beef producers more than fruit growers right now, but fruit growers need to pay attention to these trends, said Chad Kruger, director of Washington State University’s Wenatchee Tree Fruit Research and Extension Center and Center for Sustaining Agriculture and Natural Resources.

Fruit buyers are showing more interest in soil health, for example, and the connections between soil and carbon, Kruger said.

“If we’re going to sell into a global marketplace that cares about climate and carbon, we need to know where we are now and get our ducks in order,” Kruger said.

—by Matt Milkovich

Leave A Comment