(Aurora Lee/Good Fruit Grower illustration)

This is the third article in a a series about a major research project on enhancing biological control in tree fruits.

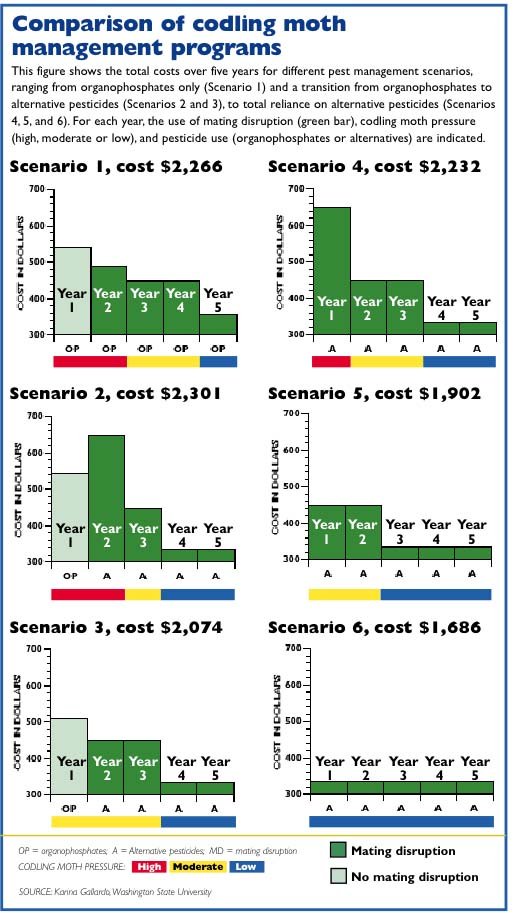

Although using new pesticides might seem more expensive than a standard organophosphate program for controlling codling moth, scientists say that’s not necessarily so in the long term. A grower could save money by transitioning from older pesticides to mating disruption and newer chemistries that are less detrimental to natural enemies.

Dr. Karina Gallardo, agricultural economist with Washington State University in Wenatchee, is one of a team of scientists working on the multistate project “Enhancing Biological Control in Western Orchards,” which is now in its third year. Her role is to help growers to be aware of the real costs and benefits behind their pesticide choices.

WSU entomologist Dr. Jay Brunner developed three different pest management scenarios in apples—each with high, moderate, or low codling moth pressure—and Gallardo created budgets to compare the costs. The scenarios are:

—A traditional organophosphate-based program

—An organophosphate program that transitioned to mating disruption and alternative pesticides

—A program using only mating disruption and alternative pesticides

Preliminary cost estimates show that where codling moth pressure is low, the alternative program costs less per season than organophosphates or organophosphates combined with mating disruption.

When alternatives pesticides are used long-term (five years), the cost is lower than a conventional program even when codling moth pressure is high to begin with (see “Comparison of codling moth management programs”). A stable and sustainable program using alternative pesticides and resulting in enhanced biological control is the least expensive in the long run.

Drs. Peter Shearer and Steve Castagnoli with Oregon State University in Hood River are developing similar scenarios for pears.

Gallardo is working with growers and consultants to validate those budgets with case studies using real data.

She’s also meeting with apple growers in Washington and pear growers in Oregon and asking them to complete a survey about their pesticide choices. Her intent is to find out what value growers place on preserving beneficial insects so that the information can be used in cost/benefit analyses.

Results of lab tests to assess whether alternative pesticides have lethal or sublethal effects on beneficial insects will also be used to determine the costs or benefits associated with certain pesticides and to measure the value of enhanced biological control. For example, if a pesticide disrupts natural enemies, there might be additional costs for sprays for secondary pests. If it does not disrupt biological control, there would be no additional costs. Indirect benefits of better biological control might also include greater worker safety and less impact on the environment because of lower pesticide use, for example.

Information that Gallardo compiles will be included in an online database to help growers choose which pesticides to use.

“I hope that will represent a useful tool for growers,” Gallardo said. “We’re going to make the information available through the project’s Web site to let growers know what are the real costs behind selecting pesticides that are not benign to beneficial insects. Apparently, they cost less, but, in the end, growers might end up spending more because they have to apply extra pesticides for secondary pests.”

Gallardo also will develop a profile of the growers who are most likely to use biological control. She will do this by analyzing responses growers give about themselves and their operations in a mailed survey.

“What influences or affects the decision of a grower to develop a more biocontrol-based pest management system?” she wonders.

Gallardo is one of ten project directors from three states who are involved in the project “Enhancing Biological Control in Western Orchards,” which is partially funded by the federal Specialty Crop Research Initiative. To learn more, go to http://enhancedbc.tfrec.wsu.edu.

Leave A Comment