About an hour north of Seattle, Swans Trail Farms offers a U-pick orchard, an old-fashioned cider press and a corn maze. There’s even an old milking barn filled with hay bales, available for wedding photos.

If you’re into that.

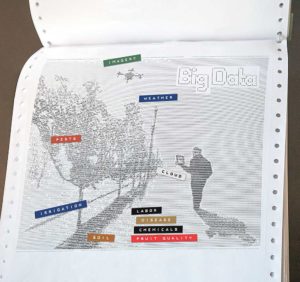

The agritainment venue also has a technological skeleton that would draw envy from any wholesale production tree fruit orchard in Central Washington, Michigan or New York.

Swans Trail was chosen as one of the first agricultural field sites for the 5G Open Innovation Lab, a Seattle-based partnership of government, universities and technology businesses looking for ways to make industries more connected through 5G — the latest generation of cellular network technology that can move a lot more data a lot faster than the networks our cellphones have relied on the past few years.Microsoft, T-Mobile and Intel are among the innovation lab’s corporate sponsors, while energy, transportation and space travel are just a few of its other arenas.

A hay farm in Arlington, another 20 minutes north of Seattle, is the other ag test site, so far. The two venues are equipped with data servers and cellular antennae to enable “edge computing” and allow movement of vast amounts of data between sensors and devices in areas with historically poor cell coverage.

Eventually, the 5G Open Innovation Lab aims to build more agricultural labs among Eastern Washington’s specialty crops, such as wine grapes and tree fruit.

Growers in those areas are hungry for technology, such as crop estimation imagery and soil scanning, but unreliable cellular service is one thing that stands in the way. However, cell companies don’t see enough scale in hilly, rural regions to warrant constructing a network to handle the sheer volume of data that such innovations require, said Kurt Steck, managing partner of the 5G Open Innovation Lab.

“There never will be enough cellphones in the area to drive the economics,” Steck said.

Steck and his colleagues hope the lab farms attract enough technology startups to convince those cellular providers that opportunity also lies in on-farm innovations, such as driverless tractors, that require connectivity.

The innovation lab currently is shopping for a public entity, such as the U.S. Department of Agriculture, to provide grant funding to pay for the technological infrastructure to make it happen at Eastern Washington test sites.

Right now, lack of rural connectivity is merely a hassle, said Jeff Cleveringa, head of research and development for Starr Ranch Growers in Wenatchee. Just drive a mile or so up the road to complete that phone call or look up something on a smartphone.

But the technology rapidly moving from row crops into specialty crops will require more than that.

“Over time, it’s just going to start climbing, this need for data movement and connectivity,” Cleveringa said.

A combination of economic incentive and government help is needed to meet that need, he said. Growers can’t all pay for their own private networks, the same way individual homeowners can’t pay for their own dam or wind turbines for electricity.

That’s where the 5G Open Innovation Lab can help, he said.

“Somebody has got to start the ball rolling,” he said.

Enter Swans Trail Farms

While the lab leaders search for a funding partner, they did stumble onto an opportunity to get their feet wet closer to home — their home anyway.

Using a $1 million food resiliency grant from the federal pandemic response CARES Act, Snohomish County hired 5G Open Innovation Lab and its partners to install the systems at Swans Trail Farms, located in a valley of spotty cell service — though minutes from Interstate 5 and the city of Everett, north of Seattle.

“It’s awful,” said Nate Krause, whose family owns the farm, of the cell service. Before the improvement, some of his office workers visited a nearby laundromat to poach Wi-Fi strong enough to download photos for the company’s website.

More than a year ago, the innovation lab used the grant money to help Krause install a Meter Group weather station, the kind sanctioned by Washington State University’s AgWeatherNet, and soil sensors to inform his irrigation decisions. Before that, he just guessed.

“It was a shot in the dark,” Krause said. “We had no idea how much water a tree needed.”

He now waters three hours every four or five days, instead of 12 hours.

Cell coverage, spotty though it is, would have been fine for soil sensor readings, Krause said. But it would not move the massive data sets he receives from Steve Mantle, owner of Walla Walla-based ag data startup innov8.ag and facilitator of Washington’s Smart Orchard project. Mantle has been driving his ATV — mounted with sensors for soil nutrient composition, canopy volume and fruit density — through Krause’s orchard. But so far, Mantle has had to crunch the data elsewhere.

The backbone of the Swans Trail improvements, a data server — about the size of a refrigerator — in the milking barn, should allow that imagery to be analyzed on-site. This local processing is known as edge computing, so called because it’s close to the point of data creation but far away from the giant data centers that support the cloud. Meanwhile, cellular antennae on the roof of the barn ping to a T-Mobile tower, recently upgraded with 5G technology, about 3 miles away.

The two structures together give Krause a private network that can crunch data locally and communicate with the rest of the internet, opening the door to numerous forms of technology — automated spraying or drone field mapping — all talking to each other as the Internet of Things.

Jim Brisimitzis, general partner of the innovation lab, hopes to see that capability at all farms someday — as a starting point for technology adoption, not the only solution, of course.

“That’s what we’re chipping away at,” Brisimitzis said.

Farming needs this, said Krause, who receives no compensation for the work and experimentation. He agreed to work with the innovation lab to help agriculture catch up with the technology of other industries and find ways to feed more people with fewer resources.

“I feel like agriculture is so far behind on technology,” he said.

And he gets to learn. The program is how he found out that digital soil sensors and complex canopy imagery are useful for growers of his scale.

“I’m not a tech savvy person, but you don’t have to be,” he said.

—by Ross Courtney

Future vision

The techies behind T-Mobile’s 5G&me tech experience have a vision for the apple orchard of the future.

Guided by artificial intelligence, a robotic arm fastened to a driverless ATV picks fruit into a bin that tracks its own remaining capacity. All manner of schematics detail soil conditions, fruit quality, light penetration and fruit-to-leaf ratios. Drones zip around everywhere.

That’s the vision visitors can experience at the company’s Bellevue, Washington, corporate campus where 5G&me, an immersive showcase, imagines how 5G applications could transform the way we live, work and play.

Rounding out the possibilities are automated telehealth pods that come to you, street corner garbage cans that keep track of their own CO2 levels and meetings held in self-driving cars.

Oh, and those grocery store “meet your grower” banners? Those would be life-sized interactive videos triggered by barcode.

A lot of it is pie-in-the-sky stuff, said Jimmy Mwangi, technology product manager. “Inspirational, imaginative,” he called it.

But not all, he added. Telehealth is already available, and farmers already use self-driving tractors.

“There are pieces of this already happening,” he said.

—R. Courtney

Leave A Comment