Apple and pear rots are not just warehouse problems.

Fungal pathogens infect pome fruit throughout the season and therefore require season-long vigilance in the trees, according to two Northwest tree fruit pathologists.

“What happens in the orchard is very important,” Achour Amiri, a Washington State University plant pathologist, said at the North Central Washington Pear Day in January in Wenatchee.

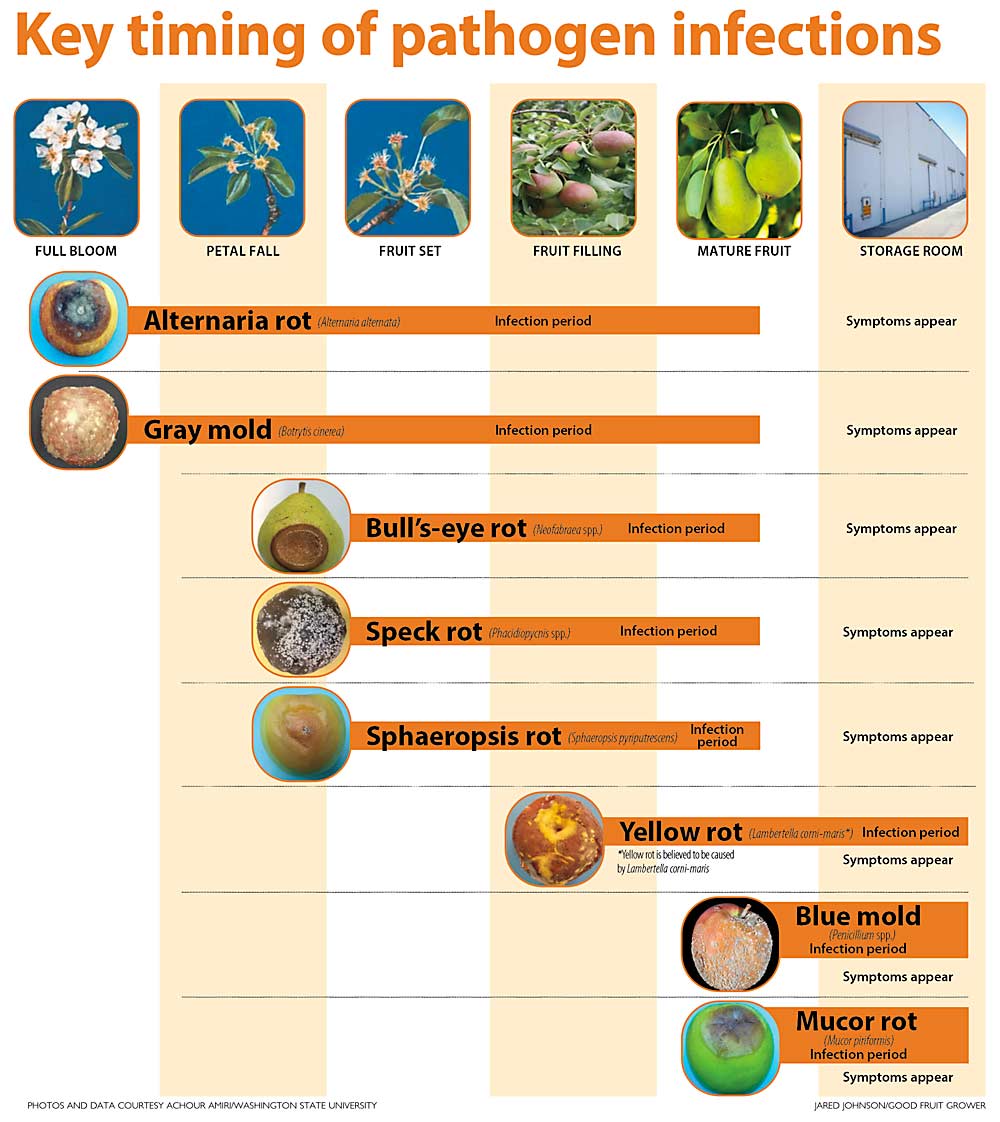

Of the eight most damaging fungal pathogens for the apple and pear industries, six of them infect fruit during the season, well before harvest. However, they only manifest symptoms in storage. Alternaria alternata, the pathogen that causes ubiquitous alternaria rot, and Botrytis cinerea, which leads to gray mold, strike as early as full bloom.

Thus, treating rot only at harvest or in the warehouse is like fighting an illness by treating only the symptoms, Amiri said. Yet, more than half of Washington growers may not be spraying at all until harvest, assuming disease pressure is low earlier in the year, according to Amiri’s conversations with industry members.

To reduce the risk of resistance, Amiri recommends growers rotate Fungicide Resistance Action Committee (FRAC) groups between years — in case some pathogens survive winter, which they can do. “Our goal is to break this cycle,” he said. Orchard sanitation helps, too, because fungal pathogens can overwinter in mummies or dead vegetation that fell to the ground.

He also recommends rotating FRAC groups within the season.

In apples, applying at least three sprays at the right times during a season resulted in less rot in storage, Amiri told the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission in an update on his commission-funded research project in late January. The first spray should be sometime between petal fall and initial fruit set, the second around midsummer and the last shortly before harvest. The trend seems to hold for organic substances, though his research is ongoing for that.

He also is working with WSU’s agricultural economist Karina Gallardo to create a cost-benefit analysis of more rot pathogen treatments.

Achala KC of Oregon State University’s Southern Oregon Research and Extension Center near Medford told a similar story at the Washington State Tree Fruit Association Annual Meeting in December in Yakima.

The pathologist’s research has convinced her that fungicide treatments throughout the growing season better prevent rot after fruit reaches cold storage. However, the industry standard is to treat at harvest and postharvest. She urges growers to view rot pathogen control as a whole system and apply multiple interventions in that system, KC said.

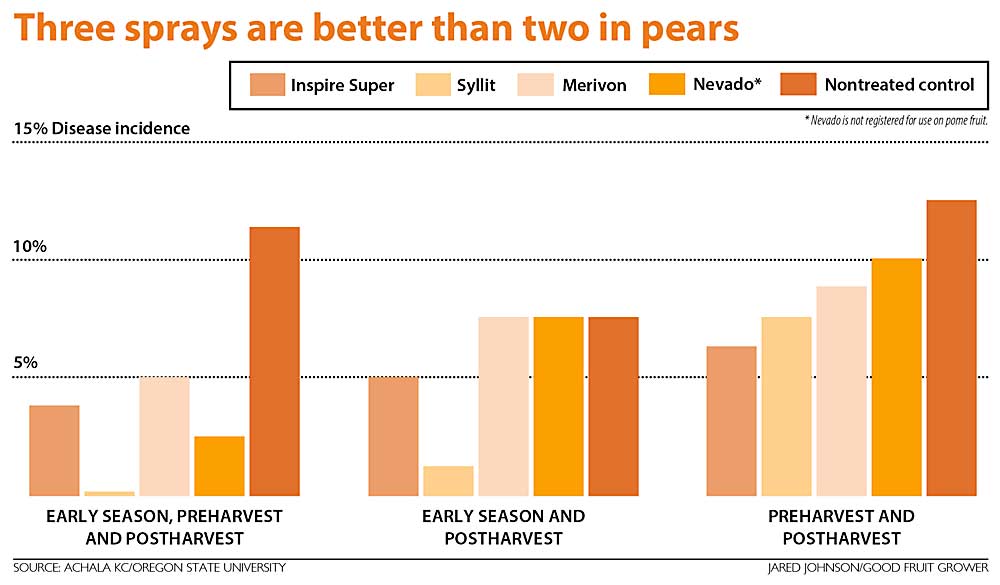

In her research trials from 2017–2018, fungicide treatments three times a year — bloom, preharvest and postharvest — significantly reduced the incidence of rot that showed up in storage, compared with twice a year. Combining early-season and postharvest treatments was somewhat better than spraying only preharvest and postharvest, which she called the industry standard.

The results generally held up over a variety of fungicides with different FRAC groups. Fungicides Syllit (dodine) and Nevado (iprodione) performed the best in the three-treatment group, but all fungicides performed better than the untreated control group. In both two-treatment groups, many of the fungicides showed no statistical difference from the control.

Nevado is not registered for apples or pears, but she tested it in case someday it becomes registered. It is used in other crops.

The results tell her that fungal pathogens colonize flowers and fruitlets long before growers use conventional preharvest sprays. Once that fruit hits storage, sugars develop, and those pathogens manifest into rot.

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment