Ancient peach pits recently unearthed in China indicate that peaches were being cultivated in China at least 7,000 years ago.

Evidence found during recent archaeological excavations in the lower Yangtze River Valley in southern China, not far from Shanghai, suggests that peaches were domesticated in that area thousands of years ago and probably originated there, rather than in northwestern China as previously thought.

Domestication means that people were consciously selecting for preferred fruit traits, by clonal reproduction, rather than just planting the seeds of their favorite fruits.

Dr. Gary Crawford, anthropologist at the University of Toronto Mississauga in Canada, has been studying the origins of agricultural crops in China for the past 20 years, in collaboration with Chinese researchers.

Most of the research in southern China has focused on rice, but Crawford, whose expertise is in identification and analysis of plant remains, published a research paper several years ago in which he urged scientists to look at the bigger picture in the region and study other crops.

Yunfei Zheng, a botanist and archaeologist at the Zhejiang Institute of Archeology in China, began showing Crawford more and more plant remains that had been recovered from archaeological digs in the lower Yangtze River Valley in Zhejiang Province.

Because peach pits were found at multiple settlements dating back over a long period, Crawford and Zheng felt peaches would be a good candidate for further study. They wondered, for example, when the evolution from the wild peach to the far superior modern peach began.

Wild peaches

Wild peaches tended to have a thin, tough, flesh. Cultivated peaches are larger and have a greater volume of flesh in proportion to the stone. Modern varieties also have a wider range of maturity times than wild peaches, allowing for a supply of fruit over a longer period. Wild species tend to be mid- to late-maturing.

Peach seeds have great genetic variability. If people grew peach trees from seeds, there would be no guarantees the new tree would produce similar fruit to the parent tree. But, trees producing large fruit could easily have been selected and propagated using rootstocks and grafting.

“If they simply started grafting, it would guarantee the orchard would have the peaches they wanted,” Crawford said.

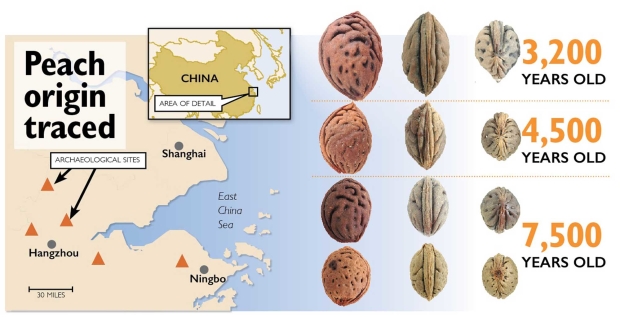

The scientists examined peach stones from five archaeological sites in Zhejiang Province in southwest China. The stones were among other relics, such as pottery, tools, and animal and other plant remains found at settlements spanning a period of about 5,000 years.

Radiocarbon dating, conducted by Direct AMS in Seattle, Washington, showed that the oldest peach stones were between 8,000 and 7,500 years old and the most recent about 3,500 years old.

Cultivated peach stones are larger and more oval than wild peach stones, whereas wild peach stones are rounder. The largest peach stones, most resembling today’s peaches, were found in the most recent site dating back to the Qianshanyang and Maqiao cultures (3,500 to 4,200 years ago).

Crawford and his colleagues think it took about 3,000 years for the peach to evolve from the wild species to that point, indicating that the domestication process likely began around more than 7,000 years ago.

“We’re suggesting that, very early on, people understood grafting and vegetative reproduction, because it sped up selection,” said Crawford. “If they had their wits about them, with vegetative reproduction and thinning, they could slowly and surely develop forms of peaches that were sweeter, and fleshier, and tastier.”

This differs from the traditional view, that people of that era were hunters and gatherers who were at the mercy of their environment.

“There is a sense in some circles that people in the past were not as smart as we are,” said Crawford. “The reality is that they were modern humans with the brain capacity and talents we have now. People have been changing the environment to suit their needs for a very long time, and the domestication of peaches along with rice helps us understand this.”

Diversity

Although peaches are now grown around the world, China has the greatest genetic diversity of peach, with 495 recognized cultivars. Crawford believes that as peaches moved to different growing regions in China, diversification increased. People started selecting the varieties that their particular towns or families liked.

Though the scientists established that peaches were in the process of being domesticated 7,000 years ago, they do not yet know when the evolution began. This summer, Crawford went to China for a month to examine remains at an older site in Zhejiang Province dating back to around 11,000 to 8,000 years ago. He took a research team from Canada with him.

Though rice is the primary focus of the project, Crawford said he was hoping to find records of other plants, such as peaches. The Chinese scientists will conduct the excavations, and the Canadians will serve as consultants and do specific research projects.

“It’s incredibly exciting,” said Crawford, who has five years of funding for the work.

This will follow from the previous work demonstrating that people who lived thousands of years ago were very knowledgeable about plant reproduction and selection.

“Now, the job is to look at how much more extensive that was,” he said. “These are not simply passive people. These are people who were managing the environment, selecting plants, and engaging with organisms in such a way they were changing their evolutionary path.”•

How would this fit in with the discovery of a fossilized pit that looks just like modern day peach from 2.5 million years ago? I think this could change everything.

https://news.psu.edu/story/382824/2015/11/30/research/eat-paleo-peach-first-fossil-peaches-discovered-southwest-china

Imagine that it looks just like a stone