Running your own rootstock trial will do more than answer your own questions.

If enough growers do it, the entire Washington wine grape industry will begin to better understand the seemingly infinite combinations of rootstocks, scion and growing conditions — important nuances as the industry shifts from a long history of own-rooted vines to using rootstocks to protect against phylloxera and nematodes, as well as usher in an era of more precise vineyard management.

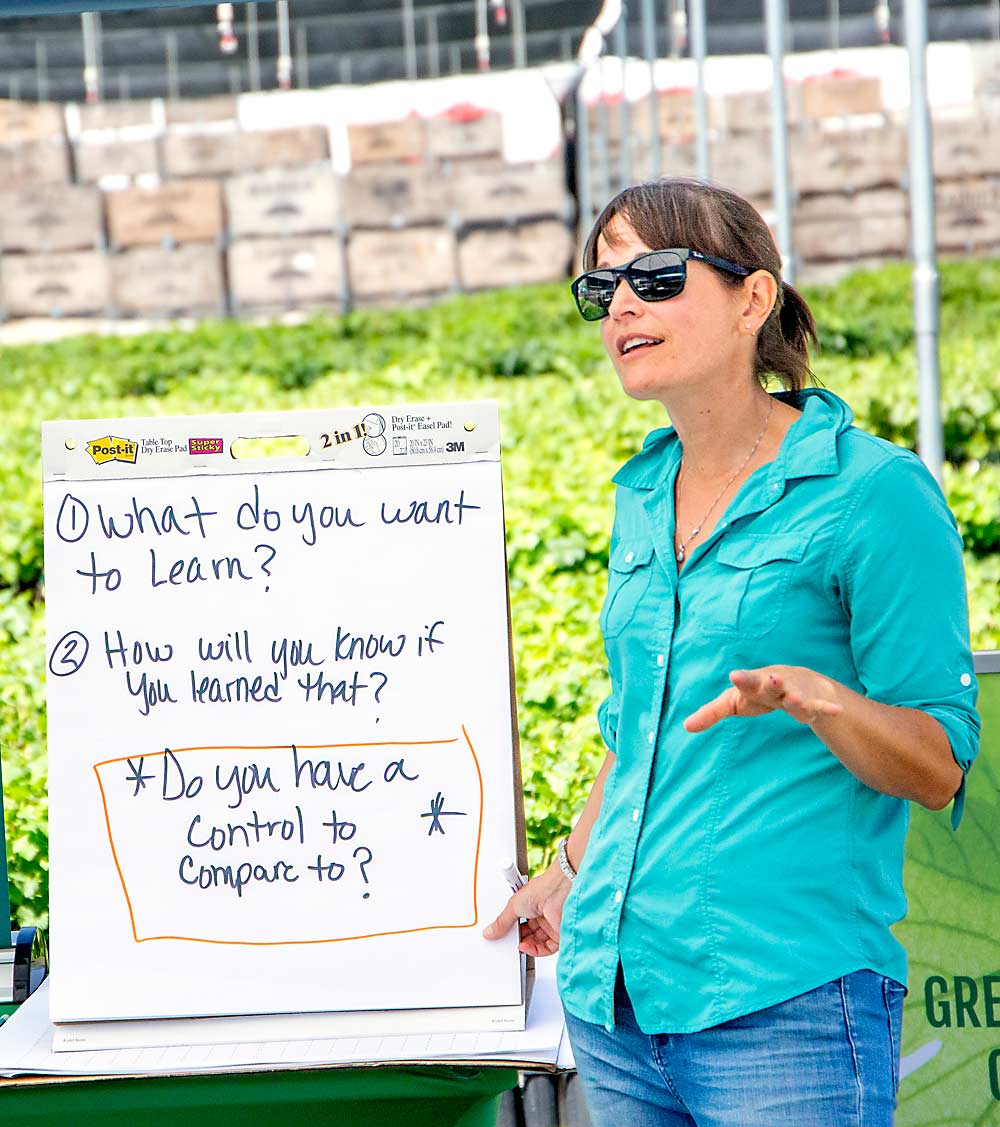

Researchers can’t do it all, Washington State University extension specialist Michelle Moyer told a group of growers at a July field day near Benton City. So, she encouraged them to do their own trials.

“Rootstock trials in general don’t have to be hard,” she said.

Despite industry contraction in the wake of Ste. Michelle Wine Estates’ cutbacks, Kevin Judkins of Inland Desert Nursery expects demand for grafted vines to continue. His Benton City company, one of the largest suppliers in the state,aims to produce 25,000 grafts per day.

“It buys us a little bit of time to get up to speed, is the optimistic way to look at it,” he said. His business also has clients in Canada, California and other areas. Currently, most grafted vines in Washington are being brought in from California, Judkins said.

Back to those trials.

In 2016, Moyer and her WSU extension colleagues published a guide called “On-farm Vineyard Trials: A Grower’s Guide” that defines terms such as treatment, randomization and replication. The 22-page document even covers formulas for statistical analysis.

But before going forward, she advises backing up.

“Before you even think about a trial, ask yourself, ‘What do I want to learn?’” she said.

Sounds obvious, but sometimes people don’t have clear goals. For a rootstock trial, a grower may want to study berry size, cold hardiness or nutrition needs. So far, researchers have determined that some grafted vines take up more potassium than own-rooted vinifera vines, but that may differ from site to site.

Moyer also suggests realistic time estimates. “It’s a long-term commitment if you truly want to do an on-farm trial correctly,” she said.

Here are a few other tips she shared at the field day:

—Know the difference between a research trial and demonstration trial. A research trial involves replication, randomization and buffer rows to hold up under peer review. An on-farm demonstration trial can be just one row comparing how the same scion grows on different roots. You could see the results from your truck.

—Bounce your design off the extension team or neighbors before planting, to catch mistakes before they happen. For example, for an irrigation trial, you may inadvertently commit yourself to laying extra water lines.

—It’s better to do a small trial well than a big trial poorly.

—Data collection consistency is more important than frequency and volume. If you measure shoot growth later than you meant to the first year, measure at the same time every year. Likewise, you may want to log budbreak for every scion, but that means checking buds every day. Instead, consider collecting data April 1 and April 20 each year. At least you’ll have consistent measurements of each scion’s timing relative to each other.

Real-world examples

While rootstock trials will need to grow for years before growers can glean firm conclusions, commercial vineyard trials on other topics show the value of the approach.

Yun Zhang and her colleagues at Ste. Michelle Wine Estates held a two-year, on-farm trial about leafing in Sauvignon Blanc, a variety typically not leafed to minimize sun exposure. However, the cultivar is prone to rot, and leafing can mitigate that.

To find a balance, Ste. Michelle decided to try leafing at bloom instead of after fruit set — a common leafing time — hoping to give the canopy more chance to grow back and shade the fruit later in the season when the weather gets hot.

“That’s kind of the balance we’re trying to play with,” Zhang said.

For two years, they ran leafing machines over one-third of each of two 30-acre blocks. In 2022, rot pressure was too low across the board for conclusive results. In 2023, however, the early leafed grapes showed only 1 percent rot incidence while the non-leafed vines — the control — had close to 5 percent. Neither year showed any sunburn.

That’s not a huge difference in rot, and the small sample size would not stand up to academic scrutiny, but the data helped them at their jobs.

Ciel du Cheval Vineyard on Red Mountain near Benton City is known for on-farm trials. One involves using Brix distribution measurements to build a predictive harvest model. Another uses artificial intelligence to automate deficit irrigation based on soil moisture.

Some of those trials are complex and warrant publication, said Kade Casciato, vineyard manager and viticulturist. Others are simple. But they all scratch his curiousity itch and make him want to know more.

“It’s been a wild ride, but it’s been a lot of fun,” he said.

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment