Intense storms in Pennsylvania in recent years felled trees, split apples and washed out orchard driveways.

Take September 2021, for example. Extreme winds and rains started with the remnants of Hurricane Ida and were followed by other intense storms in the following weeks. The ground was so saturated at Keim Orchards in Boyertown, Pennsylvania, about an hour northwest of Philadelphia, that hundreds of older, freestanding trees toppled. The rain washed out a lot of orchard driveways, too, especially on hillsides, said director of field operations Ben Keim.

Rain events have become “real downpours” in the past few years, with so much water hitting in such short periods that the soil can’t absorb it, and it runs right off, said owner Richard Keim, Ben’s father.

“We’ll go two months without, then get 6 to 7 inches within a week,” Ben said. “We don’t get steady rain anymore. We get gully washers.”

It’s hard to prepare for storms that strong, but growers seeing the trend toward heavier and more frequent downpours are looking for ways to adapt and avert disaster, including replacing freestanding trees with trellised systems more likely to stand through storms.

For the Keims, gully washers destroyed many of their orchard driveways in 2018 and have hit so frequently in the years since that they can’t keep the driveways rebuilt — costing them $25,000 or so in materials alone.

“When we get another heavy rain, it takes out a bunch of what we repaired,” Richard said. “We can’t gain ground.”

Ben said they also lost between 200 and 250 freestanding trees last September, scattered over five or six blocks. The trees were primarily Fuji and Golden Delicious, between 12 and 20 years old and spaced roughly 10 by 20 feet. They won’t replant the lost trees until they tear out the surrounding blocks to make room for higher-density plantings, he said.

The farm’s high-density, trellised plantings, spaced mostly at 3- by 12-feet, held up with little damage, Ben said.

The rains hit during harvest — a bad time to be dealing with flooding and felled trees. Fearing that cracking or other water damage would emerge in long-term storage, the Keims tried to sell all their Honeycrisp by mid-November, Ben said.

Richard said they’re still trying to figure out good long-term strategies to mitigate flood damage in their orchards. They’ll probably start by getting advice from the Natural Resources Conservation Service, which has helped them with soil erosion in the past. Any strategy they come up with, such as a diversion ditch, is sure to be costly, he said.

The September storms didn’t hit as hard in Adams County, a few hours to the southwest, but still did some damage.

Mt. Ridge Farms is used to one 6-inch rain event per year, vice president Blake Slaybaugh said. But last September, three 6-inch rain events hit within a couple of weeks. The heavy rains greatly complicated harvest: Severely saturated ground and damaged orchard driveways prevented them from entering certain blocks. The rain sized up their fruit, giving them a heavier-than-expected crop load. Pressure from apple scab and other diseases intensified.

The saturated soil also caused about 5 acres of trees to topple. They lost some freestanding Red Delicious and Golden Delicious, as well as a trellised block of Cameo, planted eight or nine years ago at a 5- by 15-foot spacing. They were in the midst of grafting over the Cameos with Honeycrisp when the trees fell, Slaybaugh said.

“There was a huge crop load on top,” he said. “Once trees started to go, they all went.”

They lost all the Cameo and Honeycrisp in that block. Slaybaugh estimates the apples were worth between $5,000 and $10,000.

They plan to replant the block with double-leader Galas. As with all their new plantings, they’ll install stronger trellises to deal with the increasingly erratic weather. Four- or 5-inch posts placed every 25 feet have worked well. Their newer, sturdier plantings survived last September’s storms intact, Slaybaugh said.

Penn State University pomologist Jim Schupp said many growers suffered significant economic damage from the storm remnants that passed through last September. Honeycrisp bore the biggest hit with fruit cracking, as most were nearly ready to harvest when the deluges struck. He recommends mixing Premier Honeycrisp with other standard-maturity Honeycrisp strains. Premier, which ripens two weeks earlier than standard strains, would increase the likelihood that some Honeycrisp survive heavy rain events.

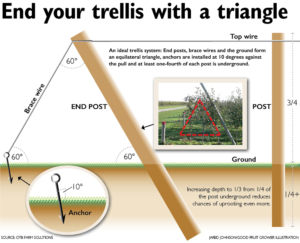

Schupp also recommends buying crop insurance, selecting well-drained planting sites or tiling fields prone to high water, avoiding excessively clean or wide herbicide strips, and building robust trellises.

Adams County grower Ben Lerew puts a lot of thought into strengthening his trellises. He pounds 5- or 6-inch posts 3 feet into the ground and avoids spacing the posts too far apart, which would weaken the system. Because winds in the region typically move from west to east, he strings trellis wires on the west side of the posts. The posts help support the wires when wind pushes the trees against them. Wires strung on the east side of the posts would pull the posts downward, making the trellis more likely to topple, he said.

Lerew typically tiles fields that have histories of drainage problems, placing 5- or 6-inch perforated pipes under the soil to drain excess water. The curvature of some of his tree rows, which wrap around hillsides, also aids drainage. The curved rows prevent water from running down herbicide strips and washing away dirt at the graft unions, and the grass between rows helps slow and spread water. Curved rows require more posts, but they are worth the extra expense, he said.

Last September’s downpours cracked a lot of his Honeycrisp but didn’t upend any trees, Lerew said.

—by Matt Milkovich

Leave A Comment