Growers battling spotted wing drosophila would love a biocontrol agent to keep the fruit fly in check. But in order for a specialized biocontrol such as the parasitic wasp Ganaspis brasiliensis to establish, it needs a regular source of SWD to sustain itself.

Meanwhile, berry and cherry growers want no SWD.

That’s a catch-22 that could complicate the goal of biocontrol. So, in Oregon’s Willamette Valley, scientists hope to take advantage of another invasive species: the Himalayan blackberry commonly found in the unmanaged areas around farms.

“The blueberry fields we work in are very clean,” said Jana Lee, research entomologist for the U.S. Department of Agriculture and leader of a USDA-funded Areawide SWD management project with sites in Oregon, California and Washington. “But the wild blackberry and hosts surrounding the farm, that’s where the Ganaspis can hopefully establish.”

Himalayan blackberry already hosts populations of SWD, one of the challenges growers in the region face to manage the pest. It’s hoped that liability can become an asset if Ganaspis and other parasitoids can establish there, protected from pesticides, and start to offer landscape-level control of SWD.

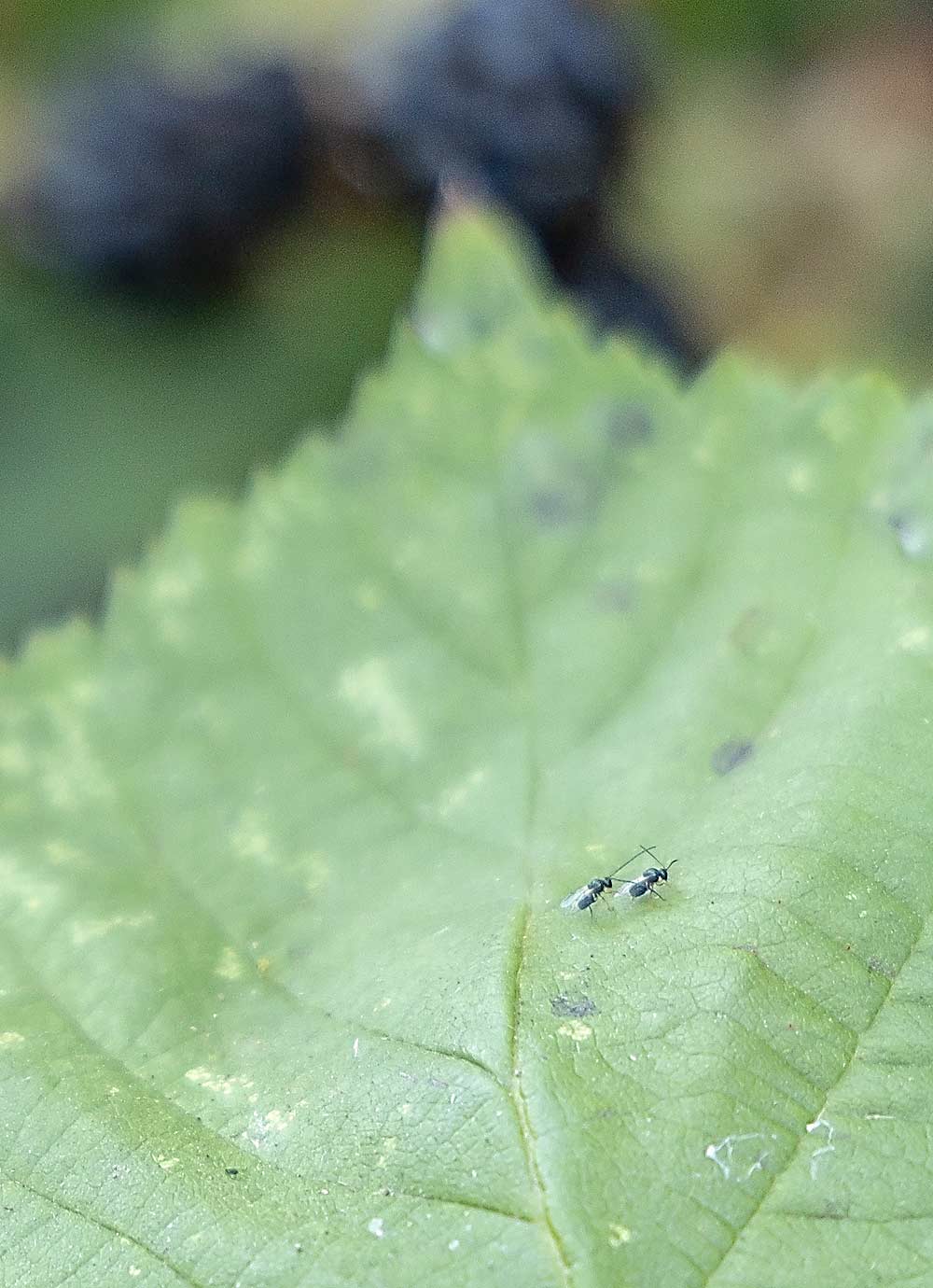

After a decade of evaluation, the USDA approved Ganaspis for release in late 2021. Last summer, Lee began release trials to see if the species can establish around commercial fruit operations at meaningful population levels to tamp down SWD pressure.

That meant first figuring out how to keep Ganaspis alive in the lab long enough to reproduce.

“It was stressful at first,” Lee said of her team’s efforts to develop a system to rear the tiny wasps that parasitize SWD larvae within fruit. The rearing system also needs SWD-infested blueberries and honey that serves as a snack for the adult wasps, along with antifungal products to keep the blueberries from rotting and a cotton pad to provide moisture but prevent puddles that the tiny wasps were prone to drown in.

At first, the wasps tended to develop a male bias, Lee said. But then the team discovered smaller containers created more successful mating conditions.

“They just want to be in their own condos,” said Eric Janasov, a researcher in Lee’s lab.

He harvests the wasps three times per week, with several hundred each time.

By late last summer they had their system dialed in, with some 500 Ganaspis wasps awaiting release in small plastic lunch containers when Good Fruit Grower visited in early September.

The Oregon releases started in July, and by September Lee’s lab was producing enough wasps to share with a research team at Washington State University.

To study parasitism, Lee and Janasov set up a monitoring network of traps around the blueberry farm hosting the trial, which they check weekly. Monitoring requires two types of traps. First, a “death trap,” a liquid trap in a peanut butter jar filled with a mix of wine and apple cider vinegar, assesses the level of SWD pressure in the area. Then, “sentinel traps” are set out, containing infected blueberries from their lab colonies and protected by a mesh lid that allows the wasps to get in to parasitize the larvae but keeps out other, larger insects.

They placed these pairs of traps in both the blueberry fields and the blackberry brambles around the farm, and they also collected blackberries to check for parasitism.

At the end of the season, the blackberries delivered the good news.

“We found Ganaspis at the site, about 4,000 feet away from the release across the farm, in Himalayan blackberry,” Lee said. At her release site, the blackberry fruit was dried out, but at the wetter location with juicier fruit she found several instances of parasitism.

In the sentinel traps, Lee and her team found evidence of parasitism by two other wasp species. One, Pachycrepoideus vindemmiae, is a pupal parasite Lee and colleagues at Oregon State University have seen on and off over the past few years.

Finding the second, Leptopilina japonica, was a more exciting surprise, Lee said. The wasp had been considered by the USDA as a biocontrol, and some researchers favored it, but it was not approved for release. However, it was found to have made its own way to Western Washington in 2021 — identified by WSU entomologist Betsy Beers in wild blackberry. She also found Ganaspis.

The good news: Lee didn’t just find one Leptopilina; at one site she found one for every 75 SWD emerging from blackberry fruit samples.

“It sounds low, but for our first time seeing that species in the field, it’s exciting,” she said. “It will probably go up with time.”

This year, Lee and her colleagues plan to continue Ganaspis releases, explore the potential of Leptopilina releases with state regulators, and keep monitoring.

“We want to see impacts on the SWD pressure,” she said, but that may take several more years to observe while parasitoid populations continue to build as they hope.

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment