Microbes found within native Northwest riparian trees appear to fight off fire blight. It’s one of many ways the tree fruit industry could benefit from the emerging research into how the microbiome can boost plant health.

Sharon Doty, a University of Washington researcher, leads two tree fruit-focused projects related to harnessing the potential of microbes that allow native trees to thrive in nutrient-scant soils of rocky Northwest riverbanks. One focuses on the microbes’ — known as endophytes because they live inside plant tissue — biocontrol action against pathogens, the other on overall promotion of plant health.

Doty is something of a microbiology rock star. Her lab has been involved with Superfund cleanup projects and space missions, and she has been featured in Smithsonian Magazine, on NPR and in The New York Times. Some headlines promise her work could “slash your dinner’s carbon footprint” and “replace fertilizers.”

She leads the plant microbiology lab in the School of Environmental and Forestry Sciences at UW.

Biocontrol

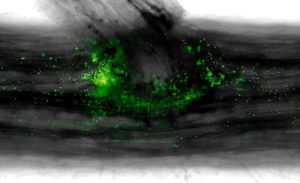

In her biocontrol study, Doty’s research suggests endophytes from native trees could inhibit diseases, such as fire blight or gray mold, if applied to roots through fertigation. In laboratory trials, isolates of endophytes visibly repelled pathogens smeared on petri dishes.

In early February, she delivered the results to the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission, which funded a one-year study for $46,000. The research commission recently awarded her another year of funding. She is currently sequencing the genetics of 15 of the more promising isolates.

To find the endophytes, Doty and research scientist Andrew Sher used tissue from native plants — such as willow, poplar and dogwood — from streambeds near Wenatchee, Entiat, Yakima and the Methow Valley fruit production areas, trying to capitalize on potential co-evolution. “When there’s co-evolution, there’s always natural biological warfare going on,” Doty said in a phone interview.

In the lab, Sher found dozens of hits against fire blight.

“You can see that some of them just completely killed it,” Doty said.

Some endophytes may even secrete a chemical in the air that pushes back gray mold. Some of her populations, dollops on a petri dish full of pathogen, seemed to bubble as they pushed back the disease.

The pair of researchers isolated 40 strains of microbes that inhibited Erwinia amylovora, the bacterium that causes fire blight; 38 that inhibited speck rot; 27 strains that inhibited gray mold; and more.

In previous work, Doty found two endophyte strains that inhibited two forms of root rot.

All in all, she has isolated and screened 119 strains for biocontrol properties.

Overall health promotion

At a research commission presentation in January 2020, Doty introduced to the tree fruit industry the idea that nitrogen-fixing endophytes can boost the overall growth and health of plants. She described how certain bacteria in willow and poplar fix atmospheric nitrogen into a form their host trees can use, allowing them to grow straight out of river rock while fertilized only by nutrient-poor snow runoff.

For 20 years, Doty has worked on isolating those strains into forms that help plants. A California company sells some of them to use on crops, including tomatoes and strawberries. She’s briefly tried this on apples. In a small, potted plant trial at the UW Seattle campus, Honeycrisp trees dosed with endophytes outgrew their untreated counterparts. They also had higher soluble sugars.

Now, Doty has funding to study this issue specifically for tree fruit at a larger scale, thanks to a three-year $246,000 Specialty Crop Block Grant. Lee Kalcsits and Bernardita Sallato of Washington State University are working with Doty.

Kalcsits, a physiologist at WSU in Wenatchee, will begin inoculating fruit trees in a Wenatchee greenhouse this summer with a microbial mixture from Doty, looking for evidence that the microorganisms confer resistance to abiotic stress or improve nutrient uptake, he said.

“It could have implications on tree management,” he said. “But first, we need to understand the biological effect and the implications on tree productivity and fruit quality before the industry will be willing to make the leap and adopt this technology.”

Sallato, a Prosser-based extension specialist with background in soil and nutrition, will look for growers to host trials. She suspects plenty will be willing to try out Doty’s formulas.

“Growers are very good about trying new things here in Washington,” she said. “They are already trying a lot of products related to microorganisms to improve soil health, root growth, et cetera, et cetera.”

The biocontrol research is especially promising if the endophytes end up registered for organic control of rot, said Jeff Cleveringa, head of research and development for Oneonta Starr Ranch Growers and a member of the research commission. The health promotion work could give growers another tool to find replant consistency.

“Most growers are not buying more new acres but dealing with the old dogs that have to come out,” Cleveringa said. “Growers would adopt it if it showed better tree growth.” •

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment