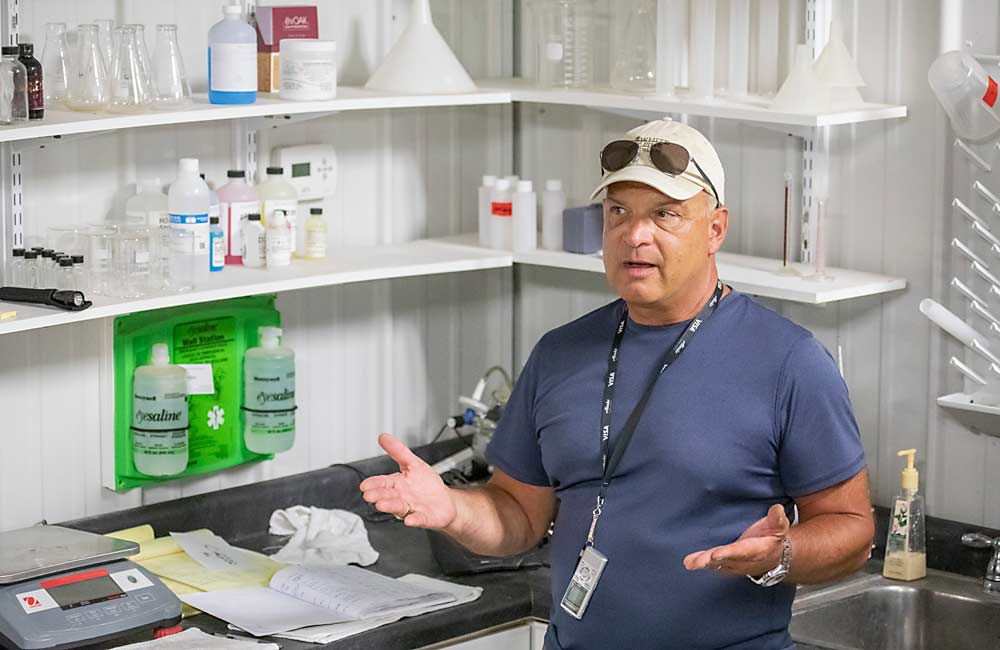

With a foot in both the academic and commercial worlds, Dave Miller has viewed the wine industry from every conceivable angle over the past few decades. He’s been a student and a teacher, a winemaker and a winery owner. He’s gotten his hands dirty in the vineyards, first doing experimental research then using that experience to grow his own grapes.

These days, Miller is busy running White Pine Winery in Lawton, Michigan, and boosting the Southwest Michigan wine industry. The region is home to most of the state’s grapes, and its proximity to Lake Michigan not only protects vineyards from weather extremes but draws an abundance of tourists.

“Dave’s combination of technical knowledge and passion have been a big part of the growth and development of wines in our region,” said Brian Lesperance, vice president of Fenn Valley Vineyards in Southwest Michigan. “Simply put, we would not be here without him.”

Charlie Edson, a winemaker and former winery owner, has known Miller since both were graduate students at Michigan State University, studying viticulture and enology with Stanley Howell, the late professor and viticulturist who played a major role in the growth of Michigan’s grape and wine industry.

“Dave quickly became enamored with growing grapes and making wine, particularly in Michigan,” Edson said. “His research background gave him a leg up, fully understanding the science and principles behind both processes.”

Going his own way

Walking through his 5-acre vineyard in June, Miller said the Lawton site — which he first started planting in 1999 — gets colder than vineyards nearer to Lake Michigan, but it’s at a higher elevation and has good clay loam soil with a deep, well-drained layer of sand underneath.

He said winter kill and crown gall have been his most consistent problems, forcing multiple replants. The risk of killing freezes doesn’t usually end until the second half of May. A Mother’s Day freeze killed his Chardonnay vines a couple of years ago, so now he buys Chardonnay grapes from growers closer to the lakeshore.

“We have gotten frost on Mother’s Day weekend more often than I’d like to count,” Miller said.

To combat crown gall, he prunes infected vines first, then sanitizes his equipment before pruning uninfected vines. He also stopped buying vines from California nurseries, which don’t treat for crown gall because it’s not a problem in their warmer climate. He’s had much better luck with clonal materials and rootstocks from a New York nursery, he said.

Miller uses the vertical shoot position trellis system. His grapes are picked by hand, which gives him more control over the winemaking process, he said.

But operating a small vineyard comes with challenges.

Miller contracts with a neighboring grower to spray his vines. Reliable labor is harder to find and is a problem shared by other small growers. He can still rally a handful of local pickers for harvest, but they’re getting older and often can only pick on weekends, he said.

“I’ve been talking to other growers, and we don’t have good answers,” Miller said about the labor situation. “It’s a little unnerving.”

Finding his path

Miller, who grew up in South Bend, Indiana, first became interested in wine while working at a ski resort in Colorado, where he noticed how popular the drink was among skiers.

So, he enrolled as a graduate student at MSU in 1983. He spent a dozen years as Howell’s technician, producing experimental wines and managing research plots and graduate projects. He also earned his doctorate, focused on grapevine photosynthesis.

In 1997, Miller took a winemaking job at St. Julian Winery in Paw Paw, Michigan’s oldest and largest winery. He still teaches a winemaking class at MSU, but since joining St. Julian he has spent most of his time on the commercial side of the industry.

At St. Julian, Miller made award-winning wines and shared his viticulture experience with the winery’s grape suppliers, to help them improve the quality of their fruit. When he planted his own plot of grapevines in nearby Lawton in 1999, he and his wife, Sandy, named the plot Sophie’s Vineyard, after their daughter.

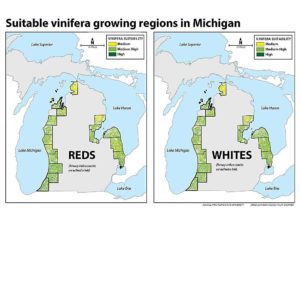

Miller chose vinifera varieties for his first planting. When he was studying viticulture in the 1980s, people were still trying to figure out if vinifera grapes could survive Michigan’s climate. It turns out they can, at least along Lake Michigan, but some varieties do better than others. Miller chose Riesling and Cabernet Franc for their cold hardiness and ability to make excellent wines in cool climates, he said.

Over the years, he added the hybrids Chambourcin, Marquette and Traminette to his vineyard. His next planting might include Pinot Grigio, but for now he gets Pinot Grigio grapes and juice from other growers, he said.

After a dozen years at St. Julian, Miller decided to further his dream of showcasing Southwest Michigan wine by starting his own winery. He had a particular business model in mind: “Doing small lots from special parcels and not blending them out.”

Miller named his business White Pine Winery, after Michigan’s state tree. In 2010, he opened a tasting room in St. Joseph, on the shore of Lake Michigan. Fenn Valley Vineyards crushed his grapes for a few years and still bottles his wines. He wouldn’t have been able to start his business without their help, he said.

Now, Miller plans to expand his Lawton facility, opening a second tasting room and increasing production space. There are many small lakes nearby, and tourists would like a place to relax and enjoy some wine, and maybe a charcuterie board, he said.

“I think it’ll be the first of many you’ll see in this area,” he said.

Now 62, Miller doesn’t show any signs of slowing down. His winery produces about 1,500 cases a year, and he’d like to bump that up to 2,500 or so. He makes sweeter wines for casual consumers, but his real passion is making the kind of “next level” wines connoisseurs rave about.

“People come in and say, ‘Dude, you’re doing it,’” Miller said. “So that makes my day, because we’re trying to show what’s possible.”

—by Matt Milkovich

Leave A Comment