The global coronavirus pandemic doesn’t offer many bright spots, but all the families at home together are buying more juice, jelly and jam, helping to boost prices for Concord growers across the country.

Combine that with supply and demand finding a better balance as growers pulled acreage in recent years, and “there’s a lot of positivity” in the juice grape industry, said Trent Ball, director of the Yakima Valley College Vineyard and Winery Technology program.

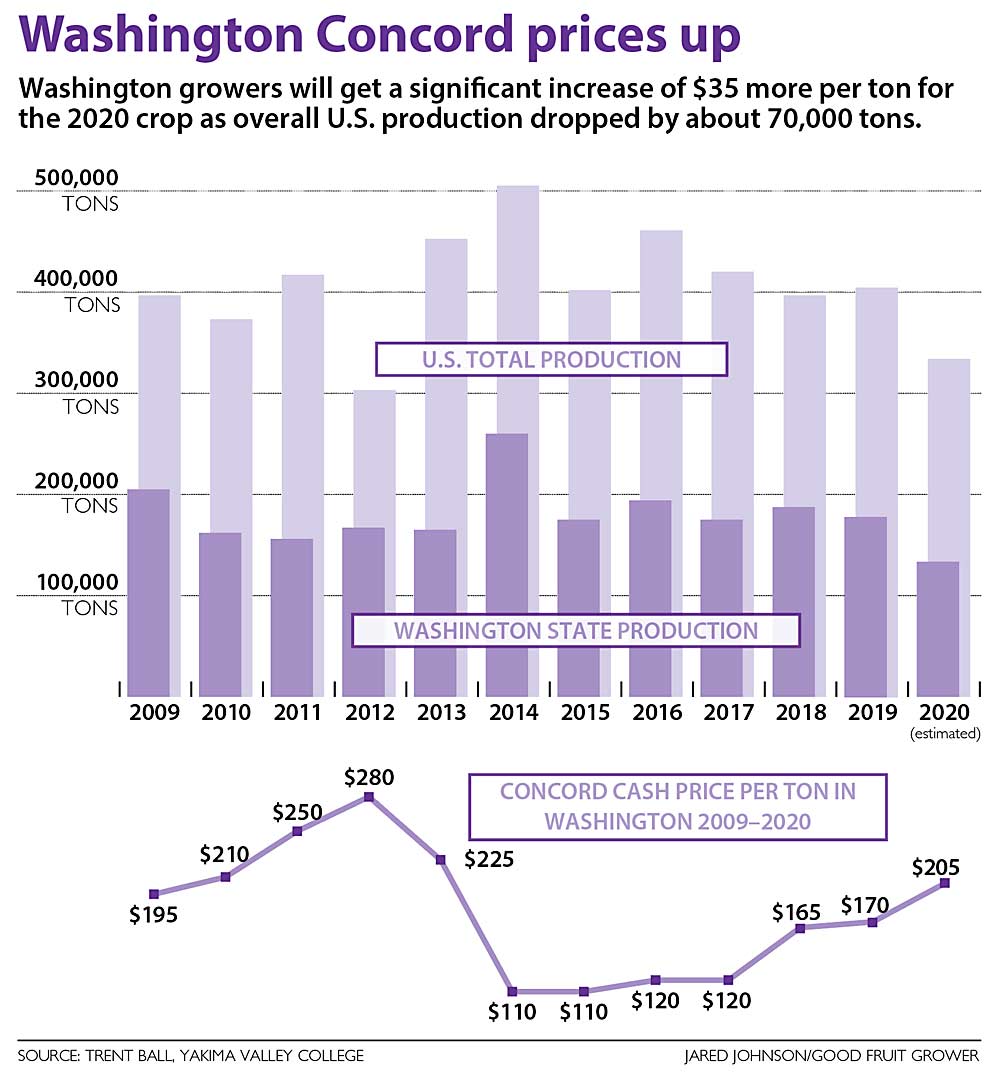

In Washington, growers received a cash price of $205 a ton in 2020, while in the Eastern U.S. the cash price hit $285 per ton. That’s up from $170 and $230, respectively, in 2019 and well above the $110 Washington growers received five years earlier.

“I still think there’s some room for additional price growth, at least in the Washington cash price,” Ball said, when he shared production and pricing numbers at the Washington State Grape Society’s annual meeting, which was held virtually in November.

Production dipped across the country, from 404,000 tons in 2019 to 333,000 tons. Production was down 15 percent from average in the East, where growers harvested around 165,000 tons. Washington growers harvested 135,000 tons, a figure that reflects both reductions in acreage and lower-than-average yields per acre.

Graphic: Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower)

Reduced yields were expected, after the early fall freezes in 2019 affected the return wood, said Mike Concienne, senior business partner with National Grape Cooperative.

“The good thing is that quality was good, sugars were good,” he said. And 2020’s growing conditions, early harvest and low yields are “a pretty good recipe for good potential the following year, but that doesn’t mean we are going to (get it). Mother Nature has the last say.”

Ball said the stage was set for a strong market in 2021. The gap between the Eastern and Western prices, which is normally closer to $30, along with the low inventories, low 2020 production and increased demand for all juice, are positive, although he balanced that with the potential of a larger crop nationwide.

Even in a high-yielding year, production is unlikely to reach previous levels, Ball said. Washington growers now farm only 16,600 acres of Concords after a steady decline since 2014. Removals appear to be slowing, he added.

“There seems to be a lot of optimism in the juice grape industry here in Washington,” Concienne said. “Supply is in really good shape and we expect things to continue to be strong.”

Wine harvest way down

The fall freezes in 2019 also appeared to cut into vine productivity for Washington’s wine grape growers.

Ball said the 2020 wine grape harvest for the state fell well below the crop forecast of 260,000 tons, with growers harvesting about 175,000 tons according to estimates from the Washington Winegrowers Association.

“That’s the lowest since 2011 or 2012,” he said.

Washington Winegrowers executive director Vicky Scharlau said many factors contributed to the light crop. The growth in wine sales was slowing pre-pandemic, and growers in Washington and California were already starting to respond to market signals by pulling out underperforming blocks, she said.

“Then, we get to the end of 2019, we’re still looking at the impacts of the freezes; there’s the out-of-balance supply and demand; and then in March COVID hits; then in the summer multiple wildfires hit; and then by the time harvest rolls around, the industry was very surprised that the crop was coming in a lot lighter than we anticipated,” Scharlau said.

Several vineyards in Washington had their grapes rejected due to smoke damage concerns, while some wineries reduced their usual contracts due to having too much unsold inventory and a lack of tank space, she added.

“You put all those together and it turned out to be a much lower crush estimate than our crop estimate,” she said. “But even with all that, what was harvested is amazing.”

That quality is good news, and the industry is relieved to see a light at the end of the pandemic tunnel, Scharlau said, but optimism for better demand in 2021 remains cautious, she said.

Wine sales slowed nearly 19 percent in the first half of 2020, according to an economic impact study authored by Ball. He estimated the pandemic would cost growers $71 million in decreased grape sales for the year. Wineries that heavily depend on tasting rooms, restaurant sales and events have been hit the hardest, he said.

For example, the Walter Clore Wine and Culinary Center in Prosser closed over the summer. The building’s owner, the economic development agency Port of Benton, announced in November that the closure was permanent and it was looking for a new operator.

“Some wineries, their model is working; they are very online and wine-club dependent. Others are just holding on,” Ball said. “I think there’s a legitimate concern that the slowed sales and reduced growth is going to continue into 2021. The longer we are in these lockdowns and stay-at-home orders, it has a negative impact on wine sales.”

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment