Mentioning the phrase “hang time” in a room of winemakers and wine grape growers is a sure-fire way to generate debate. Washington State’s wine industry discussed the controversial issue in search of middle ground during a recent state wine industry convention.

Mentioning the phrase “hang time” in a room of winemakers and wine grape growers is a sure-fire way to generate debate. Washington State’s wine industry discussed the controversial issue in search of middle ground during a recent state wine industry convention.

The contentious subject has pitted grower against winemaker, with growers watching their tonnage shrivel as the grapes hang on the vine to achieve the winemaker’s nod for harvest and winemakers waiting for grapes to fully mature and develop optimum flavors.

In Washington’s wine industry, the issue has not reached the same pitch as in California, where a series of grower-winemaker meetings were held and research reports compiled. But in the more northern region, hang time is even more important because growers must prepare vines for winter temperatures. Washington vineyardists must carefully manage the vines during late summer and fall to ensure proper hardening off and lignification of the canes as insurance against cold temperatures that can damage next season’s buds.

Since the 1980s, grape sugar levels or Brix have crept from industry averages of 24° Brix to levels of 27° and 28° Brix.

The demand for riper grapes is market-driven. Consumers now prefer fruit-forward flavors, soft tannins, and complex aromas. And many of the high-alcohol wines are receiving high scores from wine critics. When dealing with high-sugar grapes that will yield high-alcohol wines if the grapes are made directly into wine, wineries can legally add water back to reduce the Brix level and bring about more efficient fermentation.

Grower’s view

David Michul, vice president of viticultural and vineyard operations at Beckstoffer Vineyards in Rutherford, California, presented a grower’s view of grape maturity at the annual meeting of the Washington Association of Wine Grape Growers held in February in Kennewick. He defined hang time as the length of time wine grapes need to develop optimum flavor in order to produce the best wine possible.

As grapes hang longer to mature, sugars accumulate, pH increases, acidity decreases, vegetative flavors decrease, and berry flavors increase, he explained.

But the real rub to growers is the diminishing fruit weight that accompanies long hang times.

Data collected by Beckstoffer from their vineyards show there is a 25 to 30 percent average weight loss as Brix increases from 24 to 28.

The extended hang time exposes grapes to greater risk of rain and fungal diseases as well as damage by birds. Growers receiving payment based on tonnage feel that they are not properly compensated for the longer hang time and lower yields.

Michul believes that grapes with the highest quality generally come from balanced vines.

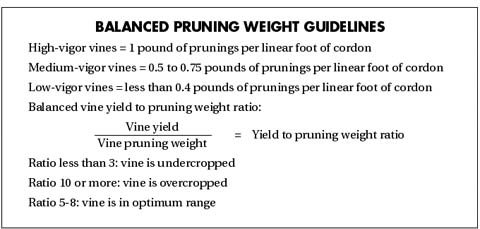

“A vine has a given capacity on a given site,” he said, adding that many factors affect a vine’s balance—soil depth, soil texture and water-holding capacity, irrigation and fertility, variety and rootstock, and such. Growers can determine their vine balance by measuring their pruning weights and striving for yield to pruning weight ratios of 5 to 8, the range identified as being “in balance.”

“Once balance is achieved, one would normally expect fruit to ripen uniformly and produce optimum flavor,” Michul said.

He noted that when looking at the berry characteristics during ripening, there is a definite growth curve and maturity phase of the berry, during which time glucose and fructose concentrates, and berry weight increases. However, past the optimum ripening time, there is a decline in some characteristics, and berry weight and quality can diminish.

“Does optimum flavor have to come at the expense of the grower?” he asked. “There is no sustainability of the industry without profits.”

Since 2000, the average tons per acre of Cabernet Sauvignon produced by Napa Valley growers declined from 4.24 tons to 2.8 tons in 2004, according to Michul. The five-year average price per ton of Cabernet in the same period is $3,685—or $12,713 per acre return to the grower based on the five-year average production of 3.45 tons per acre.

Such returns provide about 4 percent return on investment, a number that Michul believes is not financially sustainable, taking into account that capital appreciation for vineyard investments historically ranged between 10 and 15 percent.

“We’re losing 1 to 2 percent of our investment continually, year in and year out.”

Winemaker’s view

Larry Levin, vice president of winemaking for Constellation/Icon Estates, said that flavors in the berry are important, but so are economics. Levin has been a winemaker for 25 years and is involved in winemaking in both hemispheres.

“I am passionate about wine quality,” he said, adding that poor picking decisions made by the winemaker result in futile efforts to try and “fix” the grapes in the winery.

Winemakers are looking for many things, he said, when they are deciding when to harvest:

—Richness in flavor

—Roundness

—Body

—Softness

—Good quality tannins

—Length and balance

—Ripeness (lack of green characteristics).

Most of these flavor components, at least in red varietals, are found in the skins of the grapes—“a little in the seeds, but most is in the skins,” he explained.

“Wine needs to be ‘delicious’ with a softness and elegance, not painful and astringent. We don’t want tannins that are green, dry, or coarse. We do want tannins that are rich, with a soft, silky, elegant texture that adds to a wine’s rich length.”

Levin spends much of his time chewing grape skins in the vineyard, spitting out the pulp so he can concentrate just on the skins. He grinds them up in his mouth and often spits them out in his hand to look at them.

He said that when walking through a vineyard, winemakers are looking for deep, dark color and flavor, and the evolution of tannins. Ripe grapes taste like blackberry, black cherry. Tannins move from being painful to soft as the grape ripens. Griping tannins indicate the grapes are unripe, while super dry tannins signal that the grapes are too ripe.

“Quality wine flavor has little to do with numbers,” he said, referring to laboratory analysis done to determine pH, acidity, and Brix. “It’s all about flavor. Virtually all of the numbers that we look at during harvest don’t really help us.”

Levin believes that all winemakers and wine grape growers are after the same goal—making delicious wine. “The winemaker doesn’t want high-alcohol, high-sugar wines. We would rather see all of the flavors in grapes at 22° to 23.5° Brix. We want to achieve the flavors earlier, but Brix usually runs ahead of flavor.”

Solutions

Is there a middle ground for wine grape growers and winemakers on the issue of hang time?

Levin suggested that choosing better sites, using better clones and rootstocks that devigorate or ripen earlier, using irrigation to control canopy and trigger earlier ripening, and better canopy management can help encourage earlier ripening.

Winery techniques like micro-oxidation and tannin additions are used when necessary, but don’t take the place of ripe grapes, he said.

Michul believes that balanced vines are the key to optimum quality. “We’re trying to prove to the winemakers that if the vines are balanced, you don’t need to increase hang time to have optimum flavor profiles. Vine balance has everything to do with where that flavor profile comes into play.

“As growers, we need to look at vine balance so we can deliver to the winery what they want.”

Acreage contracts

Growers also have options like increasing vine spacing and eliminating excessive sun exposure to try to increase yields, he added. Mechanization can also help reduce growers’ costs.

“Another solution lies with winery contracts,” Michul said. “Tonnage contracts are in my view outdated. Acreage contracts are a viable solution and would give wineries the ability to adjust yields. Bottle price formulas should also be considered.”

Levin noted that most contracts in Chile are based on acreage. In Australia, most are tonnage contracts, though the higher-end grapes are on acreage contracts. Bottle pricing is an option, but involves many variables and can be complex.

The number of acreage contracts in California’s northern wine region is increasing, said Michul, but most contracts are still based on tonnage.

Levin agreed with Michul that yields do matter. “Otherwise, this business is not sustainable. Growers need winemakers, and winemakers need growers. We clearly cannot survive without each other.”

Leave A Comment