Almost 20 years ago, horticulturists at Cornell University set out to develop a better orchard design and the economic data to show how it performed compared to others.

They did demonstrate the benefits of the tall spindle design they developed, and more and more growers are adopting it, and they also found a whole lot of general principles.

In a presentation developed by Cornell horticulturists Dr. Terence Robinson and Steve Hoying, with economic analysis provided by Cornell Extension educator Alison DeMarree, they say a successful system:

• Produces high yields of high quality fruit

• Delivers early returns on capital investment

• Economizes on labor input

In an interview with Good Fruit Grower, DeMarree said there’s no one best orchard design for all growers and all varieties.

For a grower producing a new or highly sought after fresh market variety—perhaps a managed variety, that is experiencing high demand and good prices—a system that generates fruit quickly brings apples to a market wanting them now. It makes no sense to wait a few years to fill that demand.

“The tall spindle system is the only system we have ever tested that achieved a cumulative production of over 3,000 bushels in the first five years, resulting in approximately a 40 percent increase in crop value compared to the slender vertical axis and solaxis planting systems,” the Cornell researchers report.

Higher costs

In high-density systems, trees are planted close enough to fill the space quickly. They use less energy growing trunks, limbs, roots, and branches, and, on dwarfing rootstocks, they use the energy to grow fruit sooner rather than growing wood to support fruit later.

High-density systems need lots of trees, an artificial support system to hold all the fruit they can produce without breaking the trees, and adequate water and nutrients, from an irrigation/fertigation system, to grow the trees quickly, DeMarree said.

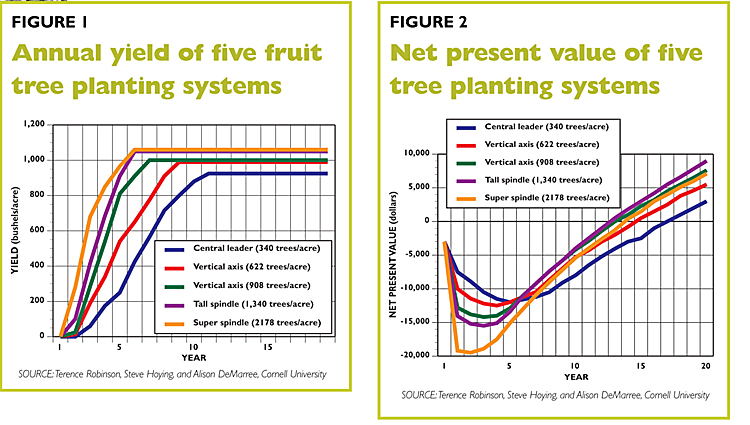

This infrastructure runs up the initial investment cost. Growers using the super spindle system, planting more than 2,000 trees per acre, incur an initial investment of around $20,000 an acre with a $6.50 tree. But, by year 12, costs should have been paid off, and by the time the trees are 15 years old, they’ll have accumulated a net present value of accumulated profit of nearly $9,000 an acre, providing fruit prices hold. Reducing the tree cost by $2 has the system breaking even in year 10 and generating a NPV of accumulated profit of $13,000 by year 15.

The tall spindle system will cost about $14,000 an acre to establish, significantly less than the super spindle because of fewer trees. It should be paid for by year 10, and should generate slightly more than $12,000 NPV of accumulated profit by year 15, assuming a $6.50 tree price.

The slender pyramid system costs even less to establish but is slower to produce fruit, and won’t break even until year 15, when it should have an accumulated NPV of accumulated profit of about $1,830 per acre.

In their studies, the Cornell experts found that fruit price had the greatest effect on profitability. A system that generates high early yields of the most valuable apples is the best.

“Tree density has a highly significant positive effect on yield,” the Cornell experts say. “The cumulative yield on the highest tree density was three times greater than the lowest density.”

When fruit prices were very high, profitability was greatest at the highest density, which was the super spindle system at 2,178 trees per acre.

When fruit prices were high, but not as high as perhaps a managed variety would generate, profitability was highest for tall spindle.

Tree price

Tree price had an effect on profitability. “Some New York growers have their own nurseries and grow their own trees,” DeMarree said. “They can afford to plant trees at a higher density.” These growers like the super spindle system.

When tree prices are very low, the optimum density was more than 2,000 trees per acres, as with the super spindle system, the researchers found.

When tree prices are high, about $8 a tree, the optimum density was about 950 trees per acre, as with the tall spindle system.

Economic considerations

Long-term profitability is maximized by planting high tree densities, the researchers say.

With high fruit prices, optimum density is high—more than 1,500 trees per acres. With moderate fruit prices, 1,000 trees is a better option.

“We believe the best combination of high profitability without excessive risk is achieved by a tall spindle planting 3 to 4 feet by 11 to 12 feet for fresh fruit blocks, a tree density of 907 to 1,320 trees per acre,” the researchers said.

The vertical axis system, with trees planted 5 to 6 feet apart in rows 14 feet apart, a tree density of 518 to 622 trees per acre, gives best results for low-priced apple varieties or for processing apple blocks.

Labor input

The tall spindle system makes good use of labor, but is demanding in the early planting years.

Tall spindle needs the best nursery stock—high quality, large, feathered trees—needs tying down or limb weighting to induce fruiting, and needs a support system of posts and wires.

But once established, trees are maintained in an easy-to-learn renewal pruning system that each year removes two or three of the largest branches, using bevel cuts to encourage new shoots to replace the branches. Branches are never allowed to get very large or become permanent, so pruning cuts are easier to make.

The formula for success, the researchers say, is to have trees supported to 10 feet of height, minimally pruned and appropriately trained, managed for a balance of growth and fruiting, with pests managed to have minimal effect on trees and fruit.

Moreover, DeMarree added, such trees are suited for partial mechanization, especially use of mobile platforms used for pruning, tree training, hand thinning, trellis work, and harvest.

12FEB18 Mr. Lehnert – Amer. Soc. Mechanical Engineers FEB 2018 mag. indicates robotic apple picking is gaining acceptance in Israel, NW USA and now maybe with Rod Farrow at Waterport, NY’s Lamont Farms. Article says with “fruit wall” type plantings, up to 90% of a crop can be auto-picked with 70% harvest still financially viable. Main equipment players are ABUNDANT ROBOTIC and FFRobotics. They also think the 80-days use for apples could be stretched by use of same grabber or vacuum robotic pickers with peaches or citrus fruits (obviously not all in same NYS orchards!). The article estimates at least 200 acres would be needed to justify a robotic picking system. Being from Columbia County, NY I was wondering about your opinion of robotic picking. Thanks in advance / Tony Winig Lebanon Springs, NY 12125 518-708-3935 cell