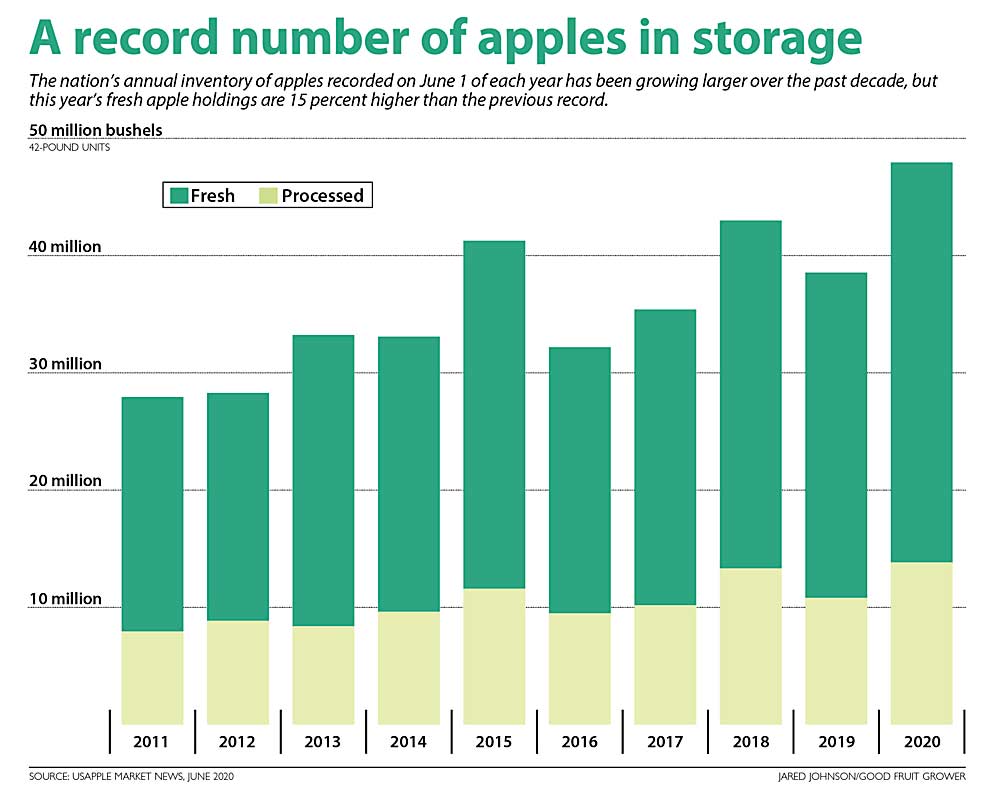

Graphic: Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower)

Trade wars and coronavirus disruptions combined to create a record number of apples in storage in June — an unprecedented inventory that was helping to push down prices to growers.

With the 2020 harvest on the horizon and pandemic-related costs rising, growers — particularly those in the Pacific Northwest — face an emergency situation and the prospect that they might have to destroy 2019 apples to make way for the new crop, according to the U.S. Apple Association.

USApple, along with other industry organizations, wrote to the U.S. Department of Agriculture on June 16, outlining the problem and seeking a reassessment on eligibility for financial aid from USDA’s Coronavirus Food Assistance Program (CFAP). The program provides direct payments to farmers who suffered price declines or lost markets due to the coronavirus pandemic. After reviewing the industry’s case, in July the USDA changed course and announced apple growers would receive payments under CFAP.

The letter asking for that support laid out the dire situation: The inventory of U.S. apples in storage on June 1 was by far the largest ever recorded, at 47.9 million bushels — 15 percent larger than the previous record and 26 percent above the five-year average. And with less than two months until the new harvest, a record-setting 19 percent of the 2019 crop remained to be marketed. As a result, the value of the 2019 crop was the lowest of any crop in a decade.

“I’ve never seen anything like this before,” said Mark Powers, president of the Northwest Horticultural Council. Things were bad when he entered the apple industry in the late 1990s, when it was dealing with the fallout from the Alar scare and the decline of Red Delicious. “It was painful back then, but from what I’m hearing from a lot of growers who were around in those days, this could be worse,” he said. “The trade war plus the COVID-19 pandemic is hitting at a time when labor costs are going through the roof. I think we will see significant economic impacts in the apple industry as a result.”

By June, the industry estimated that the cost of coronavirus-related safety measures had exceeded $1 per bushel, while reducing productivity by as much as 50 percent, according to USApple.

With its disruption of the distribution chain and upending of consumer shopping habits, the pandemic caused a definite slowdown in apple sales. But that disruption came on top of a more long-term problem: the trade wars that began in 2018, said Todd Fryhover, president of the Washington Apple Commission.

U.S. apple exports reached record lows in 2020. According to USApple, exports in the January to April period were down 21 percent from 10 years ago and down 33 percent from two years ago.

India and China, two large export markets, imposed stiff duties on U.S. apples in the past couple of years, retaliation for tariffs imposed in other economic sectors by the Trump administration.

Fryhover said the U.S. shipped 8 million boxes of apples to India in 2017–18 but only 2 million boxes in 2019–20.

“We’re sending fruit out that should have been $25 a box, but is now selling at $18,” he said.

The vast majority of the apples originally meant for export are from the Pacific Northwest. When they can’t be exported, they end up in domestic markets, driving down prices for producers in other regions, too.

CFAP

Despite the price declines caused by the pandemic, apple growers did not initially qualify for CFAP funds. To be eligible for up to $250,000 in assistance, growers had to demonstrate a 5 percent or greater price loss from mid-January to mid-April. According to USDA’s original calculations, apple growers did not experience such losses.

The industry, however, begged to differ.

According to sales data from USApple and the Washington State Tree Fruit Association, shippers report apple price declines from mid-January to mid-April ranging from 6.5 percent to 24.9 percent.

The USDA based its original price determinations on its own terminal sales data. The apple industry believed that was a flawed approach, because the vast majority of apples are shipped wholesale to supermarkets. NHC’s Powers said fewer than 10 percent of apple sales occur through terminal markets.

After reviewing the industry’s pricing and inventory data, USDA announced in July that apple growers had suffered an average price decline of 10.9 percent, and CFAP would pay them 5 cents per pound, according to USApple.

Near future

There were a few other glimmers of hope over the summer. The New York and Michigan apple crops had dwindled by June, taking a little pressure off domestic markets, said Roger Pepperl, marketing director for Stemilt Growers in Washington.

Pepperl urged sales desks to increase promotions for the 2019–20 crop, especially for bagged apples. That’s where Stemilt was putting its advertising resources. Data show that consumers were buying more prebagged apples than bulk during the pandemic.

“They want to get in and out of the grocery store quickly and buy items that don’t take a lot of time,” he said.

Apples were also being purchased via USDA’s Farmers to Families Food Box program, another component of the CFAP. The food pantries and other institutions making those purchases probably weren’t paying high prices, but it was a better alternative than dumping, Powers said.

Fryhover said that what’s left of the 2019–20 crop will most likely carry over into the 2020–21 crop. Apples from the old season might be sold at lower prices than apples from the new season. Some fruit in storage probably won’t get packed at all and might have to be dumped. Much depends on the size of Washington’s coming fresh crop.

“My personal best guess: If we get a 120 million-box crop, there won’t be any issues,” Fryhover said. “If we get 135 million boxes, it gets a little complex.” •

—by Matt Milkovich

Leave A Comment